By Michael Mann

Published in 2020

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00016

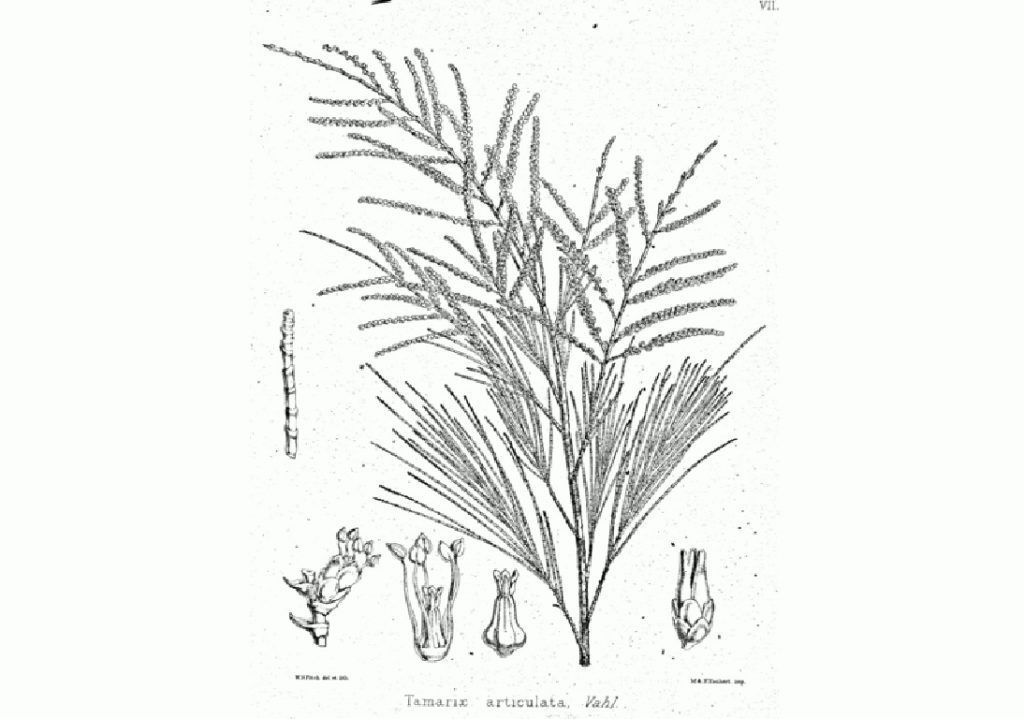

Image: A drawing of Tamarix Articulata from “The forest flora of north-west and central India (1874)” by Dietrich Brandis

This is a translated version of the 2018 MIDA Archival Reflexicon entry “Dietrich Brandis (1824 — 1907) – Botaniker und Begründer der tropischen Forstwissenschaften”. The text was translated by Rekha Rajan.

Table of Contents

Biopgraphical and Scientific Background | Inspector General of Forests | Forestry and Forest Enterprise in British India | Archival Holdings | Endnotes | Selected Bibliography for the life and works of Dietrich Brandis

Dietrich Brandis is known to many forestry scientists and some foresters as the founder of the science of tropical forestry. From 1856 till 1883 he was in British-India where he first studied the teak forests in Burma. From the time he became Inspector General of Forests in British-India in 1865, until his retirement from civil service, he was instrumental in establishing forestry in India.

However, owing to his work within the framework of the British Empire, Brandis is also known in Canada and Australia. Besides this, he is also known in the United States of America, where his expertise and advice contributed decisively to the development of forestry in the British Empire. Less well known is that Brandis was trained as a botanist and that he pursued his botanical interests throughout his life. The Brandis herbarium acquired by the Hamburg Senate in 1907 and integrated into the Institute for Plant Sciences and Microbiology of the University of Hamburg is an eloquent testimony to this.

Biographical and scientific background

Dietrich Brandis came from an academic family which was embedded in a wide family and friends’ network of scientists, who lived and/or worked in Athens, Berlin, Kiel, Copenhagen and Gӧttingen. Brandis, who as a youngster and as a student had stayed in these places, gained a broad interest in botany here. However, in the first half of the nineteenth century botany had not yet been established as a separate discipline but was combined with related subjects like geography, geology and medicine. In addition, Brandis attended lectures on classical philology, ancient philosophy, history, physics and Protestant theology. In 1849, Brandis began working as a botanist at the University of Bonn, where he was appointed as a lecturer for phytochemistry until 1855. However, his later career seems to have been blocked for unknown reasons. In 1855, he established contact with Major General Sir Henry Havelock through his wife Rachel, who was Havelock’s sister. He requested Havelock, who was serving in the British-Indian army, to find him a position as a botanist in or near Calcutta.

Within six months Brandis and his wife were in British India where Dietrich Brandis took up his position as Superintendent of Forests of the Province of Pegu (Lower Burma) in January 1856. Two years later, the provinces of Tenasserim and Martaban on the western edge of the Malay peninsula were added to the region under his control. Here, in complete ignorance of local forest conditions, Brandis developed a system to record the tree-population, the so-called “linear valuation surveys” or “strip surveys” as well as the locally practiced system of “girdling” (scratching the bark around the trunk in order to interrupt the nutritional intake) on the basis of the age and the trunk circumference of a tree in order to then let it dry out on the trunk until it was ready for felling. Along with a classification of forest areas for future forestry use, Brandis worked out principles of systematic forest management. These would be based on scientific publications and annual reports and be carried out by well-trained scientific personnel.

Inspector General of Forests

During the next quarter of the century, Brandis would be engaged in the development of forestry in British India, the aim of which was to guarantee the colonial state’s immense requirement of wood for laying railway lines in the subcontinent and for the export of tropical wood, mainly teak, deodar and sal. In 1865, the first Forest law was passed, after Brandis had gathered sufficient expertise in Burma and had been appointed as the Inspector General of Forests. The task now was to set up the office and a corresponding department (Forest Department) of the colonial administration and to create an appropriate legal basis for future action including for legal problems that might arise. Legislation initially regulated the protection of forests and their use, whereby existing legal relationships, including customary rights, were respected.

Colonial forest law culminated in the Forest Act of 1878, the main features of which are valid even today. Legislation based on the then most progressive European forest administrations of the German-speaking countries and France divided the forests of British India into three zones, namely protected, reserved and village forests, and regulated access of the local population especially to the last one. With a single stroke of the pen it annulled all existing legal relationships, including customary rights, and declared the colonial state to be the sole owner of all such designated forest areas. The colonial administration had a vested interest in securing unhindered access to the natural, and consequently, fiscal resources in the future. Although the law did not differ essentially from existing European forest laws, it was unique in its severity. Besides this, the inherent flaw in this law was that it transplanted European principles of forest administration into a non-European context without adequately taking local conditions into account.

This was certainly not Brandis’ intention because the forest and forestry legislation in central and western Europe was by far not so rigid. Moreover, in British India he was dependent on the cooperation of the local population if the forest administration was going to be profitable for silviculture and revenue. At the very least Brandis was able to ensure a broad-based training of the forest personnel in botany, geography, geology, zoology and chemistry. This indicates the holistic approach of the training and points to the function of the forest administrator as a generalist, an ideal that would change after the turn of the century in favour of the economic specialist. After consulting the Indian ministry and the colonial secretariat in India, Brandis was able to recruit two forest officials from Hessen and Hannover, Wilhelm Schlich and Bertold Ribbentrop, to help him in his manifold and almost impossible tasks. They later also succeeded Brandis in the office of Inspector General.

Forestry and Forest Enterprise in British India

In addition to other German forestry experts or botanists like Sulpiz Kurz from Augsburg, a growing number of Englishmen found employment in the upper grades of the forest services in British India, among them James Sykes Gamble and Dr. James L. Steward, both of whom made a significant contribution in cataloguing the sylvan botany of South Asia. In the same year in which the Forest Act was passed, Brandis established the Imperial Forest School in Dehra Dun, which exists even today, for training local personnel. Already in 1875, under his leadership as Inspector General of Forests, The Indian Forester, a journal, or rather a magazine with scientific essays directed at a broad readership, was launched. Brandis himself published regularly in The Indian Forester, a total of 35 articles, several of which were on forest administration, the training of forest personnel as well as on teak and bamboo. His article on measuring the requirement of railway sleepers for the railways tracks in British India is well known. (The Indian Forester 4, 4 (1879), pp. 365–85).

Along with his extensive work as the highest forest administrator and combined with his constant publications about the work being done, Brandis was hardly able to pursue his botanical interests. Occasionally he complained to his colleagues that he did not get around to collecting plants, let alone identifying them botanically. However, his two big books on the flora of British India bear witness to his intimate knowledge of South Asian flora and botany. One of these is the book begun by the aforementioned Dr. Steward on the Forest Flora of North-West and Central India which was completed by Brandis and finally published in 1874. Brandis completed the book in the two years that he spent at home to cure his failing health, and it was universally praised for its thoroughness with regards to flora, fauna, climate and geography. Brandis had already gained a reputation with his article “Rainfall and Forest Trees in India”, published in 1871, in which he had emphasized the connection between the geographical distribution of trees and the climatic conditions of a region and had illustrated this with a map that remained unsurpassed for a long time (Ocean Highways 4 (1872), pp. 200–206. Reprinted in Transactions of the Scottish Arboricultural Society 7 (1873), pp. 88–113 and The Indian Forester 9 (1883), pp. 173–83 and 221–33).

Brandis’ magnum opus Indian Trees which was published one year before his death (1906), also remained unmatched. Brandis spent at least eight years structuring and processing the material collected and provided. Indian Trees covers more than 4,400 species of trees, bushes, creepers, vines, bamboos and palms of the Indian subcontinent including the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, giving them their correct botanical names, synonyms, their colloquial names, botanical descriptions as well as related flora. Overall, the book is a monument of scientific meticulousness and of scrupulous botanical work, which establishes Dietrich Brandis as an eminent botanist, even if this was not acknowledged during his lifetime or even today. Further work on archival documents as well as on Brandis’ own publications will contribute to a new understanding of the person and the botanist Brandis.

Archival Holdings

The annual report of the Hamburg State Institute of Botany for 1908 mentioned under the rubric “purchases” that the Senate of the State of Hamburg had acquired Dietrich Brandis’ extensive botanical collection. However, one does not know why particularly the Hamburg Senate purchased Brandis’ herbarium and why no other high-ranking European botanical institute was interested in it. Evidently, during his lifetime, Brandis was famous only as a forestry scientist, which is why his extensive botanical activities with their corresponding publications were soon forgotten.[1] The fact that Brandis was an exceptionally gifted and keen botanist can be seen in the manner in which he mounted and systematized 19,000 leaves in his herbarium, which could therefore be easily integrated into the herbarium of the Hamburg Botanical Institute. This could also be a reason why the leaves are not listed individually. Already in 1911, the entire holding was incorporated, sorted as it was into species.[2]

Little is known about the further fate of Brandis’ herbarium. After the Institute for Applied Botany was established in 1913, Brandis’ wood collection was kept there. The Institute of General Botany, established in the same year, took over not only the Botanical Garden but also the herbarium of the Hamburg Botanical Museum. Parts of the extensive and bulky wood collections are in the Xylotheque of the Thünen Institute. In 2012, the Institute for General and Applied Botany was merged with the Biocenter Klein Flottbek. Further information on the Brandis herbarium can be obtained from the present head curator of the Herbarium Hamburgense, Dr. Matthias Schultz (matthias.schultz[at]uni-hamburg.de)

Endnotes

[1] Hamburgische Botanische Staatsinstitute. Jahresberichte 1908. Aus dem Jahrbuch der Hamburgischen Wissenschaftlichen Anstalten 26 (1909), p. 10.

[2] Hamburgische Botanische Staatsinstitute. Jahresberichte 1910. Aus dem Jahrbuch der Hamburgischen Wissenschaftlichen Anstalten 28 (1911), p. 8.

Selected Bibliography for the life and works of Dietrich Brandis

Guha, Ramachandra, “An Early Environmental Debate: The Making of the 1878 Forest Act”. Indian Economic and Social History Review 27, 1 (1990): pp. 65–84.

Hölzl, Richard, “Der ‚deutsche Wald‘ als Produkt eines transnationalen Wissentransfers? Forstreform in Deutschland im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert”. discussions 7 (2012), 29 pp. https://prae.perspectivia.net/publikationen/discussions/7–2012/hoelzl_wald. (Last accessed on: 03-09-2020).

Hesmer, Herbert, Leben und Werk von Dietrich Brandis 1824–1907. Begründer der tropischen Forstwirtschaft, Begründer der forstlichen Entwicklung in den USA, Botaniker und Ökologe. Abhandlungen der Rheinisch-Westfälischen Akademie der Wissenschaften: 58. Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1975.

Negi, S.S., Sir Dietrich Brandis: Father of Tropical Forestry. Dehra Dun: Bishen Sing Mahendra Pal Singh, 1991.

Prain, David, revised by Mahesh Rangarajan, “Brandis, Sir Dietrich (1824–1907)”. Oxford National Biography (1915, online edn 2004). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/32045

Rajan, Ravi, “Imperial Environtalism or Environmental Imperialism? European Forestry, Colonial Foresters and Agendas of Forest Management in British India, 1800–1900”. In: Richard H. Grove, Vinita Damodaran, Satpal Sangwan (eds.) Nature and the Orient. The Environmental History of South and Southeast Asia. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 324–371.

Rawat, Ajay S., “Brandis: The Father of Organized Forestry in India”. In: Ibid. (ed.) Indian Forestry: A Perspective. New Delhi: Indus Publishing Company, 1993, pp. 85–101.

Saldanha, Indra Munshi, “Colonialism and Professionalism: A German Forester in India”. Environment and History 2, no. 2 (1996): pp. 195–219.

Brandis, D., Forest Flora of North-West and Central India, A Handbook of the Indigenous Trees and Shrubs of those Countries. Commenced by the late J.L. Steward, continued and completed by D. Brandis. Prepared at the Herbarium of the Royal Gardens, Kew. Published under the Authority of the Secretary of State for India in Council. London: Wm H. Allen & Company, 1874.

——–, Indian Trees. An Account of Trees, Shrubs, Woody Climbers, Bamboos and Palms Indigenous or Commonly Cultivated in the British Indian Empire. London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd, 1906.

Archival Holdings

Herbarium Hamburgense, Institute of Plant Science and Microbiology, Universität Hamburg

German Letters 1858–1900, Archives, Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew

Journal

The Indian Forester

Michael Mann, IAAW, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029