By Ole Birk Laursen

Published in 2022

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00058

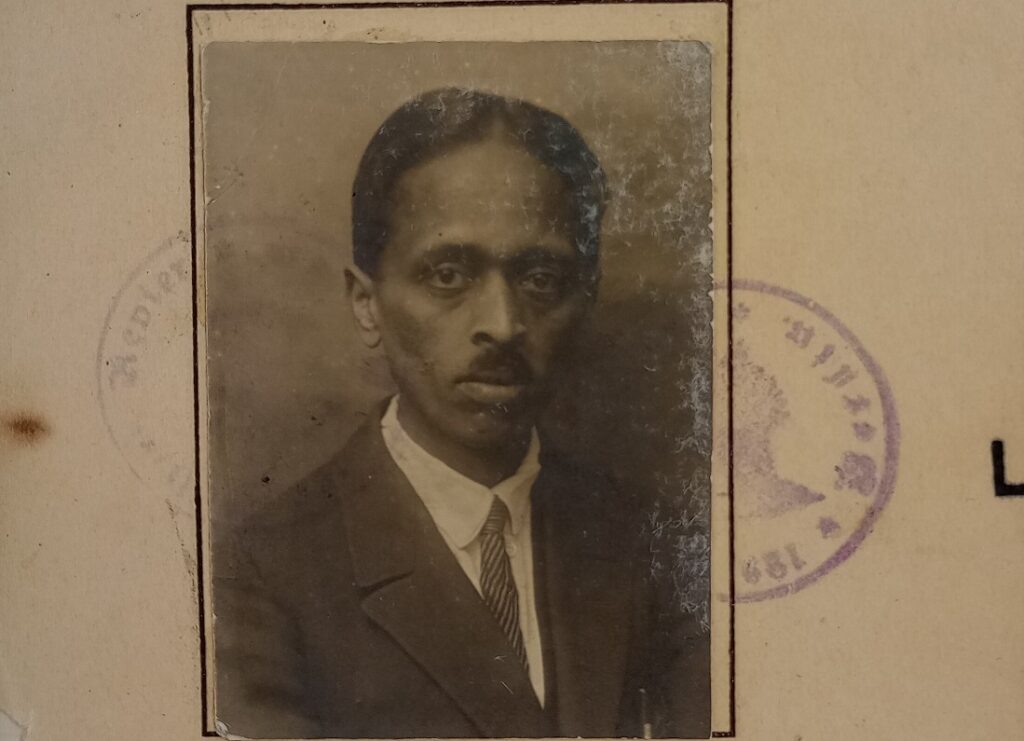

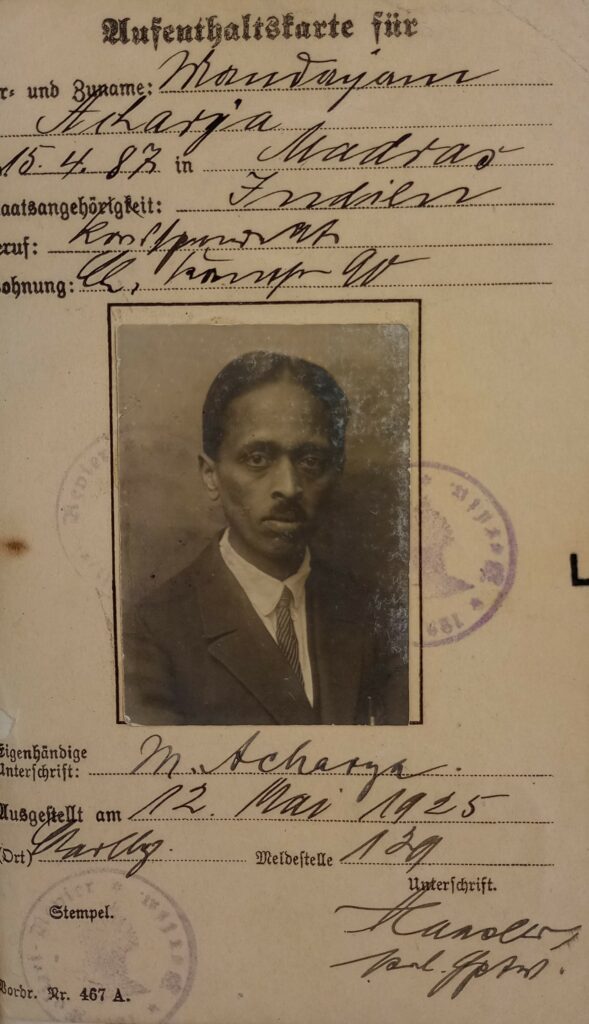

Photo: The segment of Acharya’s German residence permit containting his photo. For full image and source see Fig. 1 below.

Table of Contents

Passage to Exile | The First World War and the Indian-German Conspiracy | The Russian Revolution and State Authoritarianism | Citizenship, Passports, and Sedition in Weimar Berlin | Archival Sources | Conclusion | Endnote | Bibliography

Throughout his almost twenty-seven years in exile, the Indian revolutionary Mandayam Prativadi Bhayankaram Tirumal “M. P. T.” Acharya (1887–1954) travelled from India to Britain in 1908, to Portugal, France, Germany, Turkey, and the United States from 1909 to 1914, to Germany, the Middle East, and Sweden during the First World War, and to Russia in 1919. He then spent twelve years in Berlin from 1922 to 1934, before he escaped Nazi Germany, living underground in Switzerland and France, and finally returned to India in 1935.

Like so many Asian anti-colonialists of his generation, Acharya lived an itinerant revolutionary life in exile (Harper, 2021: 50–51). At a time of great transnational anticolonial activity, throughout war and revolution, the rise of fascism and Nazism, to travel across several continents and crossing borders was no easy task. This has also made it difficult for historians to provide a comprehensive account of Acharya’s life (Subramanyam, 1995). Based on my biography of Acharya (Laursen, forthcoming), in this essay I reflect on archival traces of this wandering revolutionary through passports and the issue of citizenship. As John Torpey argues, passports have been central to states’ “ability to ‘embrace’ their own subjects and to make distinctions between nationals and non-nationals, and to track the movements of persons in order to sustain the boundary between these two groups (whether at the border or not)” (Torpey, 2018: 2). What is more, as Radhika Mongia makes clear in relation to Indian migration, exile, and empire, the modern passport emerged “through the articulation of nation, race, and state” and, in doing so, was crucial to defining these categories in the early twentieth century (Mongia, 2018: 112).

During his time in exile, Acharya spent considerable time in Germany (1910–1911, 1922–1934) and under German protection (1914–1919), which has left several traces of him in the Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts (PA AA). In fact, in exploring his wandering life, it is informative to read files from the PA AA in conjunction with India Office Records (IOR), held in the British Library, London, files from the National Archives of India (NAI) as well as files from the North American Records Administration (NARA) to fully understand the complexities of exiled anticolonial lives and the (im)possibility of return to India. Indeed, focusing on the role of passports, the files on Acharya in the PA AA reveal a great deal about the embrace of state authority and citizenship as well as, conversely, how they evaded and subverted the watchful eyes of colonial authorities.

Passage to Exile

In November 1908, fearing imprisonment for sedition, Acharya fled India and arrived in winter-cold Marseille, proceeding immediately to Paris and, a week later, to London. In the imperial metropolis, he soon became part of the inner circle of Indian nationalists at India House and, in August 1909, with fellow India House member Sukh Sagar Dutt, ventured on a mission to join the Rif anticolonial struggles against the Spanish in Morocco (Acharya, Sep 1937: 3). For this, Acharya obtained a British passport on 16 August from the India Office in London and departed from Southampton on 18 August 1909. Acharya’s British passport has since gone missing in the IOR (IOR/L/PJ/6/956, files 3066–3070) but been recovered from the NARA (Old German Files, 1909–21, 8000–1396, M1085). Acharya failed to reach the Rifs and was soon stranded in Tangier. Meanwhile, back in India, a warrant for his arrest was issued in September 1909 for his involvement in the nationalist paper India in 1908 (NAI, Home & Political, B 1909, Dec 37). This meant that Acharya could not return to India or set foot on British territory again. However, with a British passport in hand, throughout the next two years, Acharya travelled to Lisbon, Paris, Brussels, Rotterdam, and Berlin before he arrived in Munich in the spring of 1911.

In the autumn of 1911, in an act of anti-European solidarity, Acharya wanted to join the Tripolitanians against the Italian invaders in Abyssinia. On 25 October 1911, he obtained permission to travel to Constantinople from the Ottoman consulate in Munich (NARA, Old German Files, 1909–21, 8000–1396, M1085). Spending almost seven months in Constantinople, nothing came off his efforts, and in July 1912 he escaped the watchful British authorities and fled for the United States. His two years in the US remain somewhat obscure: he worked as a farm labourer and is known to have applied for US citizenship in 1913, which was denied due to the US’s strict anti-Asian immigration laws, while also resuming his revolutionary activities and briefly joining the radical anticolonial Hindustan Association of the Pacific Coast (Ghadar Party), translating their paper Ghadr into Tamil, as well as the Hindustan Association of America in New York, but little else is known of his life there (Laursen, forthcoming).

The First World War and the Indian-German Conspiracy

Shortly after the First World War broke out, his old friend Virendranath Chattopadhyaya (‘Chatto’) set up the Indian Independence Committee (IIC) in Berlin and, with German financial and logistic backing, soon recruited exiled Indians into the committee.[1] The PA AA holds extensive files, digitized and available online, on IIC’s activities and Acharya’s involvement with the group (PA AA, RZ 201/21070–21118 – Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen gegen unsere Feinde – Indien). Records show that Acharya arrived in Berlin in December 1914 on a Persian passport provided by the Irish anticolonial revolutionary George Freeman (PA AA, RZ 201/21074–75). He left his British passport behind in New York and symbolically turned his back on British citizenship (NARA, Old German Files, 1909–21, 8000–1396, M1085). Arriving in Berlin on a Persian passport, however, soon landed him in trouble with the Berlin authorities, but the Auswärtiges Amt (AA, Foreign Office) intervened and provided him with a German ID card (Personalausweis / PA AA, RZ 201/21074–75).

In early 1915, the IIC deployed its first mission to Constantinople with the aim to collaborate with the Ottomans and undertake missions against the British throughout the Middle East. The AA provided the Indian revolutionaries with fake passports, travelling as German East Africans, and Acharya assumed the name ‘Muhammad Akbar’ (PA AA, RZ 201/21078). Throughout the next two years, Acharya and the Indian revolutionaries travelled across the Middle East, reaching Baghdad, Jerusalem, and the Suez Canal, while subverting the authority of British passports and citizenship (RZ 201/21070–RZ 201/21118).

However, little came off their efforts, and by early 1917 the IIC closed their mission in Constantinople. The 1917 February revolution in Russia and European socialist attempts to broker a peace changed the Indians’ perspectives and alliances. In May 1917, travelling on German Personalausweise, Acharya and Chatto relocated to Stockholm to bring the question of Indian independence into socialist peace negotiations. In other words, they shed their German East African identities and, while still supported by the AA, sought new alliances with European socialists and other colonial and subject peoples (PA AA, RAV 250–1/474 – Krieg 1914–1917 – Indien – Indisches Nationalkomitee in Stockholm; PA AA, RZ 201/20519 – Die internationale Sozialistenkonferenz in Stockholm, Wien und London).

They set up the Indian National Committee and agitated among European socialists. However, the social democrats in the Second International were not sympathetic to Acharya and Chatto’s efforts and even accused them of being German agents. Shortly after the end of the war in November 1918, they terminated their mission in Stockholm, but the question remained: what to do next? Reports to the AA reveal that many of the Indian revolutionaries in Stockholm and Berlin wanted to become German citizens, though it appears that none of them did, but they acquired Personalausweise and protection by the German state (PA AA, RZ 201/21117).

The Russian Revolution and State Authoritarianism

In June 1919, Acharya and a group of Indians, including Mahendra Pratap and Abdur Rabb, departed from Berlin for Moscow with German assistance (PA AA, RZ 201/21118). After meeting Lenin, the group set off for Afghanistan to exploit anti-British sentiments and recruit local Muhajirs into their campaign against the British in India. Throughout the next three years, Acharya set up the Indian Revolutionary Association (IRA) in Kabul, he attended the Second Congress of the Communist International in Petrograd and Moscow in July 1920 as a delegate of the IRA, and with M. N. Roy, Abani Mukherji, and Muhammed Shafique, he co-founded the Communist Party of India (CPI) in Tashkent in October 1920. However, Acharya soon fell out with the domineering Roy and was expelled from the CPI in January 1921. Instead, he associated with notable anarchists, criticized the Bolsheviks, and eked out a living as a journalist in Moscow, where he met and married the Russian artist, Magda Nachman (Laursen, 2020: 241–255; Bernstein, 2020: 142–159).

Citizenship, Passports, and Sedition in Weimar Berlin

By the autumn of 1922, Acharya’s presence in Moscow was no longer tolerated by the Bolshevik regime and he had to flee again. In November 1922, Acharya and Nachman arrived in Berlin on Russian passports (PA AA, RZ 207/80558). Once again, Acharya had shed his state-sanctioned identity and passport. However, as Acharya was known to the AA, the couple easily acquired permission to stay in Berlin. By the mid-1920s, the German capital had become a hub for exiled Indian revolutionaries, many of them being alumni of the IIC and communists such as Roy, causing some trouble for the German state’s diplomatic relations with Britain. Indeed, by late 1924, the two former enemies initiated discussions about deporting several notable Indians from Germany, including Acharya, Chatto, Mukherji, and Roy, illuminating the tenuous position of the exiled Indians. In the end, however, as the Germans felt they owed the Indians some degree of protection after their collaboration during the First World War and as the British did not want them on the loose in India, the deportation case was dropped (Barooah, 2018: 12–23; IOR/L/PJ/12/223; NAI, Home & Political, NA 1925, NA F‑139‑I Kw). At the same time, as files from the PA AA show, Acharya had his residence permit extended in Germany (PA AA, RZ RZ 207/80558; RZ 207/78315).

The deportation case, however, prompted Acharya to apply for a British passport to leave Germany (IOR). In his application, he stated that his passport had been stolen from his address in Berlin in 1914 and not that he had left it behind in New York. When the British refused to offer Acharya amnesty for his activities against Britain during the First World War, he abandoned the application as return seemed impossible (IOR/L/E/7/1439).

In 1929, Acharya resumed his passport application (IOR/L/PJ/6/1968, file 3981). He was not the only one. In the early 1930s, other IIC alumni such as Rishi Kesh Latta, L. P. Varma, Abdur Rahman Mansur, and A. Raman Pillai also wanted to return to India. Like Acharya, however, they found this difficult due to their activities during the First World War. The PA AA contains files with letters from these Indians, asking for financial help to return or even to be able to remain in Germany, negotiating their individual cases with the AA, while they awaited the outcome of their passport applications (PA AA, RZ 207/78314–315–316).

With the rise of Nazism in Germany, life became more dangerous for Indians in Berlin. At the same time, in India, the British were cracking down on the civil disobedience movement and arrested thousands of protesters, including leaders such as Gandhi, Nehru, and Sarojini Naidu, Chatto’s sister. This made the prospect of returning to India almost impossible. Pillai, Mansur, and Varma managed to return to India, while Latta hesitated and went to Teheran, where he died shortly after (PA AA, RZ 207/78314–315–316).

In early 1934, the British finally granted amnesty to Acharya and provided him and Nachman with British passports valid for travel to India on the condition that he would refrain from political activity (IOR/L/PJ/6/1968, file 3981). With travel money provided by the AA, Acharya and Nachman hurriedly fled Berlin in February 1934 and arrived in Switzerland, where they stayed with Nachman’s sister in Zürich. While the AA helped Acharya leave, internal correspondence in the PA AA also shows that they did not want Acharya to return to Germany (PA AA, RZ 207/78314–316).

Throughout the following year, Acharya lived clandestinely in Zürich and Paris, without legal residence papers, trying to secure money for a safe passage back to India, where he still feared that he faced the risk of imprisonment (IOR/L/PJ/6/1968, file 3981). He eventually returned to Bombay in April 1935, where Nachman joined him a year later. A life of wandering was over for Acharya, and while he remained active in the international anarchist movement, he never went to prison for his political activities. Nachman died in Bombay on 12 February 1951, and Acharya died impoverished on 20 March 1954 (Laursen, 2020: 241–255).

Archival Sources

India Office Records, British Library, London, UK

In addition to passport applications, the IOR holds Weekly Reports of the Director of Criminal Intelligence, who was responsible for tracking the activities and movements of Indian revolutionaries within India and abroad. The passport applications usually contain History Sheets of the applicants as well as correspondence regarding the application.

National Archives of India, New Delhi, India

Many of the files from the IOR are also held in the NAI and available online at https://www.abhilekh-patal.in/. These include files on Acharya’s arrest warrant, his travels to Morocco, passport applications, and the 1924 deportation case against Indians in Germany.

North American Records Administration, Maryland, USA

The NARA holds files from the Bureau of Investigation, the precursor to the FBI, on the activities of Indian revolutionaries in North America. The Old German files (1909–1921) cover the period before, during, and after the First World War, including material on the Ghadar Party and the Indian-German conspiracy during the war.

The Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts), Berlin, Germany

The PA AA holds extensive archival material on the activities and movements of Indian revolutionaries in exile during and after the First World War. The most significant are the digitized files pertaining to the IIC and First World War (RZ 201/21070–21118 – Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen gegen unsere Feinde – Indien), which also includes files on Indian soldiers held in German prisoner-of-war-camps (RZ 201/21244 – Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen gegen unsere Feinde – Tätigkeit in den Gefangenenlagern Deutschlands) and the Indian National Committee in Stockholm (RAV 250–1/474 – Krieg 1914–1917 – Indien – Indisches Nationalkomitee in Stockholm; PA AA, RZ 201/20519 – Die internationale Sozialistenkonferenz in Stockholm, Wien und London). In addition to these, the PA AA has extensive files on the political activities of Indians in Weimar Germany, including material relating to passports and expulsions (RZ 207/78314–316 – Agenten- und Spionagewesen – Orient), as well as Indian propaganda, press, and social activities emanating from Germany (RZ 207/77446 – Journalisten, Pressevertreter; RZ 207/77449 – Pressewesen; RZ 207/77461–462 – Politische und kulturelle Propaganda; RZ 207/77463 – Vereinswesen).

Conclusion

The files held in the PA AA, read alongside those in the IOR, the NAI, and the NARA, open a window onto the peripatetic lives of many Indian revolutionaries who had collaborated with the Germans during the First World War and ended up in Berlin in the interwar years. In fact, it is necessary to look beyond the binary colonial logic of archival traces – i.e., IOR (London) and NAI (Delhi) – and examine a wider web of archives to fully understand the peripatetic life of Acharya. Indeed, as I have demonstrated here, the PA AA is crucial to understanding such revolutionary lives. By focusing on passports, a state-authorised document issued to regulate and embrace individuals’ citizenship and movements, the archives illuminate both the ways in which Indian revolutionaries subverted the colonial legal apparatus through their travels as well as the difficulties for them to return to India. Acharya’s many passports reveal a great deal about the ephemeral standard of state-authorised documents in the early twentieth century which, however, eventually landed him in trouble with the authorities he was trying to evade when he wanted to return to India. At the same time, it also becomes clear that, despite being state-authorised documents, rival states contributed to subverting the authority of these documents by, at times, providing fake passports and offering hospitality to exiled revolutionaries. However, as is evident from Acharya’s case, this hospitality was contingent and relied on the German state’s embrace of its citizens, which ultimately was predicated on exclusion from as much as inclusion within its borders along the lines of race, ethnicity, and nationality.

Endnote

[1] See Heike Liebau’s entry on the Indian Independence Committee: Liebau, Heike, “‘Undertakings and Instigations’: The Berlin Indian Independence Committee in the Files of the Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office (1914–1920)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2022): 10 pp, https://www.projekt-mida.de/rechercheportal/reflexicon/, DOI: 10.25360/01–2022-00048, or the article’s original German version: Liebau, Heike, “‚Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen‘: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängigkeitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914–1920)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 11 pp, https://www.projekt-mida.de/rechercheportal/reflexicon/, DOI: 10.25360/01–2022-00007.

Bibliography

Acharya, M. P. T., “Reminiscences of a Revolutionary”, The Mahratta (July–October 1937)

Acharya, M. P. T., Ole Birk Laursen (ed.), We Are Anarchists: Essays on Anarchism, Pacifism, and the Indian Independence Movement, 1923–1953. Edinburgh: AK Press, 2019.

Barooah, Nirode K., Germany and the Indians Between the Wars. Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2018.

Bernstein, Lina, Magda Nachman: An Artist in Exile. Boston: Academic Studies Press, 2020.

Harper, Tim, Underground Asia: Global Revolutionaries and the Assault on Empire. London: Penguin Books, 2020.

Laursen, Ole Birk, “Anarchism, pure and simple: M. P. T. Acharya and the International Anarchist Movement”. Postcolonial Studies 23, 3 (2020): pp. 241–255.

——–, Anarchy or Chaos: M. P. T. Acharya and the Indian Struggle for Freedom. London: Hurst Publisher, forthcoming 2023.

Mongia, Radhika, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Subramaniam, C. S., M. P. T. Acharya: His Life and Times: Revolutionary Trends in the Early Anti-Imperialist Movements in South India and Abroad. Madras: Institute of South Indian Studies, 1995.

Torpey, John C., The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship, and the State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Ole Birk Laursen, Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029