By Alexander Benatar

Published in 2021

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00017

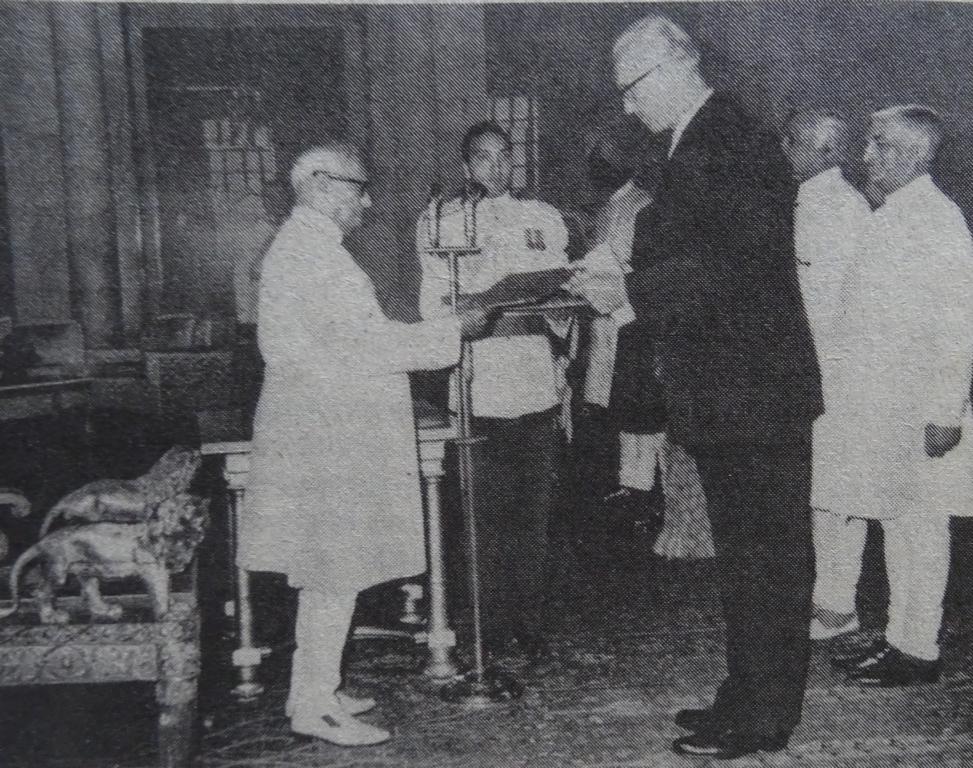

Image: Herbert Fischer (1984). DDR-Indien: Ein Diplomat berichtet. Staatsverlag der DDR, Berlin. p. 78.

This is a translated version of the 2019 MIDA Archival Reflexicon entry “Herbert Fischer – Eine deutsch-indische Verflechtungsbiografie”. The text was translated by Rekha Rajan.

Table of Contents

Early Years | With Gandhi | In the GDR | Back in the GDR | Sources | Bibliography

Herbert Fischer began as an employee of the Trade Representation of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in New Delhi, later serving as its director and consul-general. After the official recognition of the country in October 1972, he was the first ambassador of the GDR in India.

Herbert Fischer’s life is closely interwoven with the emergence of independent India as well as with the development of the GDR. Fischer had already spent a decade in India before the Second World War, had lived with Gandhi and as a German, he had been interned during the war by the British colonial rulers in India. After the war ended, he returned to his home in Saxony in Germany, which was now part of the Soviet-occupied zone and was soon to become a part of the GDR. Via circuitous routes, he arrived at and became part of the Ministry for External Affairs and soon advanced to become the India-expert of the early GDR.

Early Years

Born in 1914 in Herrnhut, Saxony, Herbert Fischer decided to leave Germany as a young man in 1933, when the National Socialists came to power. At the time he was living near the Baltic Sea with a group of followers of the Lebensreform movement. There he met, among others, Klaus Mann, the son of Thomas Mann, who had just returned from a trip to the Soviet Union and was disillusioned with his impressions of life there.

Fischer had already heard about Mohandas Gandhi, the “Mahatma”, and his non-violent resistance to British colonial rule. The 19-year old Fischer was enthused by this and decided to travel to India. After an adventurous journey through France, Spain, the Balkans, and Turkey, some of it on a bicycle, he reached the port of Bombay in 1936. In Bombay he boarded a train for Wardha, the rural place in Central India, where Gandhi had set up his ashram – the base for his countrywide work, where the Indian National Congress also held its meetings.

With Gandhi

In Wardha, Fischer saw Gandhi every day, spoke to him personally and was fascinated: “I had never experienced such veneration for a living person. I couldn’t help thinking of similar stories in the New Testament.” And:

“Gandhi was always emphatically and consciously modest, had an open ear for all questions, even if they only concerned trifling matters, was a caring father to all and did not display any desire for power. That was what made him popular, that was what made him effective. I could observe and experience this myself every day. This is what made him Bapu, father. He was also Bapu for me. I felt he was a father. To an American missionary who visited him he appeared to be a combination of Jesus Christ and his own father. Even today, I believe that I could talk to him more deeply than to my own father.”

This is what Fischer wrote in his memoirs Unterwegs zu GANDHI in 2002, 65 years later (p.77f.).

What Gandhi and Fischer had in common was their pacifism. In 1937, Fisher’s jacket was stolen along with his German passport. When the German Consulate General in Bombay informed him that his passport would only be replaced if he returned to Germany to serve his time in the military, Fischer refused and thus accepted his denaturalization.

Gandhi assigned Fischer the task to set up agricultural cooperatives in nearby Itarsi and to help in the running of a hospital. Jawaharlal Nehru, who was later the first prime minister of independent India, often visited Fischer at this railway junction. Fischer became a member of a local Quaker community and met his future wife Lucille Sibouy there, a Jamaican-born nurse with Indian roots.

When the Second World War broke out in 1939, Herbert Fischer was interned by the British colonial rulers as a citizen of an enemy state. His wife followed him with their first son Karl in early 1940. Along with other Germans, they were kept in different camps, in some of which Fischer was sometimes allowed to visit Gandhi.

In the GDR

After the war ended, Herbert Fischer and his family returned home, which was now in the Soviet-occupied zone, later on the GDR. Fischer had not received a regular education after completing school, and had trouble establishing himself in post-war Germany. In the GDR, he first found a job as a teacher and later in school administration. Through lectures about his time with Gandhi, which he gave in his spare time, he came to the attention of the newly founded Ministry of External Affairs (MfAA) of the GDR, which was desperately looking for suitable staff without a national-socialist past. In September 1956, Fischer began to work in the ministry and soon headed the India division. In January 1958, he was transferred to India as deputy director of the GDR’s Trade Representation.

The diplomats of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) looked at this new, supposed “secret weapon” from East Berlin with suspicion. Thus, in October 1959, a report on “Soviet-zone propaganda in India on the occasion of the 10-year jubilee of the so-called GDR” sent to the headquarters in Bonn, stated:

“Thanks to the skilful and charming manner displayed by Mr. Fischer, who speaks perfect Hindi and who greeted every journalist who entered with a handshake, there was a friendly atmosphere during the event.”

The West Germans were afraid of Mr. Fischer’s expertise of the country and he could, in fact, partly draw on his old pre-war contacts. This was, however, not always received well in East Berlin. When Mr. Fischer and his wife visited their old acquaintance Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, the first health minister of independent India, they happened to meet an American journalist there who, among others, quickly began asking unpleasant questions about the events of 17 June 1953, which he had witnessed in Berlin. When Fischer reported on this, the MfAA in Berlin reacted sharply:

“I would like to remind you that before your departure, colleague Schwab had expressly indicated that old acquaintances should not be renewed, or only after prior examination.”

It was not only the West German Hallstein-Doctrine but also his own superiors who put curbs on Herbert Fischer’s diplomatic work.

In September 1962 Fischer returned to East Berlin with his family to first attend the Party Academy of the GDR and to then head the India division in the headquarters of the MfAA. In August 1965 he was again transferred to India, this time as the head of the Trade Representation in New Delhi.

In the meantime, he had not lost his aura. In November 1965, a West German diplomat wrote in a report to the headquarters of the AA in Bonn: “Given Fischer’s special knowledge of the country and his political experience, it will not be easy to find someone on our side with a similar knowledge of the country.” In particular, Fischer’s good relations with the Indian prime minister, Indira Gandhi, were later emphasized again and again. These connections had arisen from the fact that both had been in Gandhi’s ashram at the same time.

For the party leadership of the SED (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands), however, other things were more important, as can be seen from a report from the end of 1966:

“There is a trend in the Representation for many comrades to criticise the head of the Representation, Comrade Fischer. They all state that he is an exceptionally good diplomat who does good work vis-à-vis the Indian side. The complaint then is that Comrade Fischer does not pay enough attention to individual comrades.”

Back in the GDR

Soon after India officially recognised the GDR in October 1972, a goal that had been achieved through Herbert Fischer’s dedication and effort, the MfAA pulled him out of his second home. In summer 1974, he was appointed head of the anti-racism committee of the GDR, which had purely representative functions. Disillusioned, he gave up this post to work as a mentor to Indian students in the SED-party academy until his retirement.

Later too, he remained faithful to India and published books which he presented there. In March 1999, his wife Lucille died after a long illness. In May 2003, the then prime minister of India, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, awarded Herbert Fischer the “Padma Bhushan”, the third-highest civilian award in India. Herbert Fischer died on 3 February, 2006 in Berlin.

Sources

Researching a fascinating biography is a comparatively rewarding historical task. To search for a specific name usually turns out to be significantly easier than the search for abstract terms and contexts, which can only be described when a logical thread has been established. The challenge is considerably lesser when describing the course of a life, especially when the protagonist has himself/herself left some records of his/her life. And Herbert Fischer was not only a Gandhian and an important GDR-diplomat, he was also a prolific writer.

Herbert Fischer’s own publications are therefore the starting point for research on him, above all his memoirs from his youth and exile in India Unterwegs zu GANDHI [Berlin, Lotos Verlag Roland Beer, 2002] as also his work as a diplomat DDR – Indien. Ein Diplomat berichtet [Berlin (Ost): Staatsverlag der DDR, 1984]. Both books are an important foundation for writing Fischer’s biography, and they can be supplemented and verified by accessing primary sources. Thus, for example, in the Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office (Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amtes / PA AA), in the holding of the Foreign Office of the German Reich, there is a file with the signature R 145638 and the title “Investigation of Germans in Enemy Territory – Individual Cases – British India – Letters FA-FL” (Nachforschungen nach Deutschen in Feindesland – Einzelfälle – Brit. Indien – Buchst. Fa – Fl) which contains a petition from Herbert Fischer’s father enquiring about his son’s whereabouts.

Unexpected insights about Fischer’s time in Indian exile are also available in the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library’s (NMML) “Oral History Interview” with Fischer, in which the Indian historian Aparna Basu tried to capture the personal impressions of Mahatma Gandhi’s fellow campaigner in 1969. Apart from this, there is also the book by Marjorie Sykes An Indian Tapestry: Quaker Threads in the History of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh from the Seventeenth Century to Independence [York: Sessions Book Trust, 1997] on the role of Quaker communities in colonial India which also consists of a few pages on Herbert Fischer and his wife.

Although Johannes H. Voigt’s Die Indienpolitik der DDR – von den Anfängen bis zur Anerkennung (1952–1972) [Kӧln/Weimar/Wien: Bӧhlau Verlag, 2008] contains some important information about Herbert Fischer’s role as a GDR diplomat in New Delhi, an analysis of Fischer’s “second life” in India is not possible without extensive research in German archives. These include the PA AA in Berlin and the Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv /BArch) with its locations in Berlin and Koblenz.

For the period until 1979, the archival holdings of the MfAA in the PA AA are organised thematically according to the principle of pertinence. Correspondence between the headquarters of the MfAA in East Berlin and the GDR Representation in New Delhi, which often contains references to Herbert Fischer, are found in the PA AA in the holding “M1 – Zentralarchiv”. In addition, the assessments of the “opposing side” are also informative. The West German AA organised its archival documents from the beginning according to the principle of provenance. The files of the country desk “IB 5 South and East Asia, Australia, New Zealand and Oceania” are in the inventory B 37 but have not yet been fully catalogued by the PA AA. Thus, archival documents for the period since 1973 are, at present, in a temporary archive. Moreover, relevant files from the FRG embassy in New Delhi are in the holding AV Neues Amt under the abbreviation NEWD.

In the Federal Archives (BArch) the SED-reports on Herbert Fischer’s work for the Party in New Delhi in the holding DY 30 are revealing, and for Fischer’s role in the GDR after he was recalled from his post as ambassador to India the private collections of his friend and colleague Siegfried Forberger in the inventory N 2536/13 are informative. Forberger not only published his own memoirs: Das DDR-Komitee für Menschenrechte: Erinnerungen an den Sozialismus-Versuch im 20. Jahrhundert; Einsichten und Irrtümer des Siegfried Forberger, Sekretär des DDR-Komitees für Menschenrechte von 1959 bis 1989 [Berlin: Selbstverlag, 2000/2007], but he also remained in contact with Herbert Fischer until Fischer’s death. Forberger’s collections include several letters and postcards that Fischer and he wrote to each other even after the turn of the millennium, as well as Herbert Fischer’s obituary of 2006. This obituary lists the names of his family members as well as the most important milestones of his biography. So far, there are no Herbert Fischer collections in the archive.

Bibliography

Fischer, Herbert, Unterwegs zu GANDHI. Berlin: Lotos Verlag Roland Beer, 2002.

——–, DDR – Indien. Ein Diplomat berichtet. Berlin (Ost): Staatsverlag der DDR, 1984.

Forberger, Siegfried, Das DDR-Komitee für Menschenrechte: Erinnerungen an den Sozialismus-Versuch im 20. Jahrhundert; Einsichten und Irrtümer des Siegfried Forberger, Sekretär des DDR-Komitees für Menschenrechte von 1959 bis 1989. Berlin: Selbstverlag, 2000/2007.

Sykes, Marjorie, An Indian Tapestry: Quaker Threads in the History of India, Pakistan & Bangladesh from the Seventeenth Century to Independence. York: Sessions Book Trust, 1997.

Voigt, Johannes H., Die Indienpolitik der DDR – von den Anfängen bis zur Anerkennung (1952–1972). Köln/Weimar/Wien: Böhlau Verlag, 2008.

Alexander Benatar, Evangelische Zentralstelle für Weltanschauungsfragen (EZW)

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029