By Jürgen‑K. Mahrenholz

Published in 2023

DOI 10.25360/01–2023-00035

Photo: A Vinyl Record

This is the corresponding English version of the 2020 MIDA Archival Reflexicon entry “Südasiatische Sprach- und Musikaufnahmen im Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin”. The text was originally published in “When the war began we heard of several kings” South Asian Prisoners in Worl War I Germany, edited by Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau, and Ravi Ahuja. New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 187–206.

Table of Contents

Wilhelm Doegen and the History of the Lautarchiv | The Phongraphic Commission | Technical and Organisational Realisation of the Gramophone Recordings in the POW Camps | South Asian Recordings in the Lautarchiv | Conclusion | Endnotes | Bibliography

This chapter gives an overview of the sound recordings of South Asian soldiers and civilians from the First World War stored in the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Prisoners of war became ‘objects’ of linguistic research when, in 1915, a commission of researchers received the official sanction to record the numerous languages and dialects that were spoken by the cosmopolitan assortment of ‘enemy’ soldiers and civilians in Germany’s prison camps. The recordings of voices, languages, dialects and music of interned soldiers and civilians for research purposes account for a significant part of the collection, but there were also other areas of focus.

In terms of scope and historical significance there is no comparable collection in any German university. This collection is the earliest and most comprehensive systematic sound archive created for documentary and scientific purposes by recording onto shellac disc. It was established for scientists by scientists for the purposes of teaching and research. On the one hand, research into phonetics, dialects, comparative linguistics, and ethnology were to be furthered; on the other, the recordings were to play a significant role in foreign language teaching. The archive, which was preserved after the Second World War though without being managed or extended, has been developed and digitalised since 1999. A database of the recordings made by the archive on shellac disc between 1915–44 has been completed and is available online.[i]

These sound recordings can only be properly appreciated in their respective scientific and historical context, which, however, has not been investigated and reconstructed in sufficient depth as yet. The following does not presume to offer a complete picture, for this reason.

Wilhelm Doegen and the History of the Lautarchiv

The history of the Lautarchiv is closely linked to its founder Wilhelm Doegen (17.3.1877–3.11.1967). Doegen was born in Berlin in the same year that Edison invented the phonograph. On finishing high school, he underwent an apprenticeship in a bank and then studied economics and business law. Doegen also went unofficially to English lectures given by Alois Brandl (1855–1940) at the Friedrich-WilhelmsUniversität (today Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin). It was Brandl who encouraged Doegen to study Modern Languages. In 1899–1900 Doegen spent one term at Oxford where he studied with Henry Sweet (1845–1912). Sweet is regarded as one of the pioneers of modern phonetics, and he played a decisive role in the development of phonetic transcription with its numerous special characters.

Doegen later described the meeting with Sweet and the latter’s system of phonetic transcription as a determining influence on his own work. In 1904, Doegen qualified as a teacher of English, French and German. His dissertation was on the use of phonetics in the teaching of English to beginners (Die Verwendung der Phonetik im Englischen Anfangsunterricht). With great enthusiasm he pursued the use of phonetic transcription in teaching materials to be used in conjunction with texts spoken onto records.

As a teacher at the Borsig High School from 1909, Doegen compiled teaching materials running to several volumes in co operation with the Odeon Recording Company in Berlin. The shellac disc was to be used as a new medium of teaching. These materials were called “Doegen’s teaching booklets for the independent learning of foreign languages with the help of phonetic transcription and the speech machine” (Doegens Unterrichtshefte für die selbständige Erlernung fremder Sprachen mit Hilfe der Lautschrift und der Sprechmaschine). In addition to this he published material using native speakers to read from classical English and French literature.

Doegen continued to work closely with the Ministry of Science, Art, and National Education and was sent by this department to the World Exposition in Brussels in 1910. There he received the silver medal for introducing the record to teaching and research. A mere two years later, some 1,000 schools and universities could be seen using Doegen’s shellac discs for language teaching. Encouraged by the success of his sound recordings, Doegen developed ideas for a voice museum (Stimmenmuseum). In February 1914, he submitted an application to the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art, and National Education to establish a Royal Prussian Phonetic Institute (Königlich Preußisches Phonetisches Institut).

In 1920, Doegen became the director of the Sound Department of the Prussian State Library (Lautabteilung an der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek). Irregularities in book-keeping led to Doegen stepping down in July 1930. In October 1931 he was, however, able to begin work again but the administration of the Lautabteilung became the responsibility of the university. In the end the Nazi law of 1933 on the establishment of a loyal and ‘Aryan’ ‘Berufsbeamtentum’ (The Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service) led to Doegen’s dismissal.

The Phongraphic Commission

According to Doegen’s “Suggestions for the establishment of a Royal Prussian Phonetic Institute” from 1914, the following were to be collected:

- Languages from around the world.

- All German dialects.

- Music and songs from around the world.

- Voices of famous people.

- Other areas of interest.[ii]

The application led to the appointment of the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission on 27 October 1915. Carl Stumpf, psychologist, acoustician, and founder of the Phonogramm-Archiv was appointed as chairman of the Commission.[iii] During the early phase of acoustic research Carl Stumpf was regarded as an indisputable authority in the field and it is therefore not surprising that the ministry entrusted him with the leadership of the new initiative.

In total, the commission comprised thirty academics working in the fields of philology, anthropology and musicology and included such prestigious scholars as Otto Dempwolff (Medicine, African Indonesian and South Seas’ languages), Felix von Luschan (Anthropology), Friedrich Carl Andreas (Iranian languages), Alois Brandl (English dialects), Adolf Dirr (Caucasian languages), Helmuth von Glasenapp (Punjabi, Hindi), August Heisenberg (Greek), George Schünemann (Musicology), Heinrich Lüders (Bengali, Paschto, Gurung).

One of the purposes of the commission was to make audio recordings in German prisoner of war camps. Between 29 December 1915 and 19 December 1918, the Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission recorded 2672 audio-media (gramophone-discs and wax cylinders) of approximately 250 languages, dialects, and traditional music among the prisoners of war of the German Empire. The members of the commission selected 31 of the existing 175 prison camps for the collection of their samples.[iv] Some of these camps were visited on more than one occasion and thus, all in all, the commission undertook 49 field trips to prison camps. With the exception of Austria, this form of gathering ethnographical material was unique during World War I. In Germany, the activities of the Phonographic Commission were kept secret during the course of the war.

Doegen himself was responsible for the purely technical production of the gramophone recordings only. Together with the subject experts and a technician he made 1650 recordings, of which two thirds were language recordings and a third music recordings. The last disc (PK 1650) was recorded shortly before Christmas 1918.

The musicologist Georg Schünemann made musical recordings exclusively with the phonograph. He worked mostly on his own and did not make use of the standardised data acquisition of the commission, which is described in the following passage. His collection consists of 1022 wax cylinders which are today kept in the Phonogramm-Archiv.[v]

In the confusion of the November Revolution of 1918, Doegen obtained personal control of the gramophone recordings through the Ministry of Education and established this collection as the basis of the Sound Department of the Prussian State Library (Lautabteilung an der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek), founded on 1 April 1920.[vi]

The Chairman of the Phonographic Commission, Carl Stumpf, was not informed of this development and reacted angrily,[vii] because as far as he was concerned the collection was to be retained by the Ministry of Education as a whole.

Instead, with the establishment of the Lautabteilung (Sound Department) the collection of the Phonographic Commission was divided according to the recording medium (shellac in the Lautabteilung, wax cylinders in the Phonogramm-Archiv) and these have been kept at two different locations ever since.

In addition to the gramophone recordings of the Phonographic Commission, the Lautabteilung also kept recordings of famous individuals, a voice collection, which was begun by Doegen in 1917. These recordings were made with financial support given by the chemistry professor Dr Ludwig Darmstaedter. According to the contract of donation, the purpose of this collection was: “Stimmen von solchen Persönlichkeiten aufzubewahren, an deren Erhaltung für die Nachwelt ein historisches Interesse vorliegt” (To retain the voices of important personalities that are of historical interest of future generations).[viii] “Personalities”, here, relates in particular to politicians, scientists and artists.

These recordings were intended to supplement the Ludwig Darmstaedter collection of autographs for the history of science, which Darmstaedter had donated to the Royal Library (Königliche Bibliothek) ten years earlier.[ix] As honorary curator of this collection Doegen had to accept the decisions made by a curatorship on new recordings. The records of this collection of voices carry the signature “Aut” (Autophon). The first official recording with the signature “Aut 1” was the speech of the German Kaiser Wilhelm II with the title “Aufruf an mein Volk” (Appeal to my People) recorded on 10 January 1918 in the Schloß Bellevue. This speech was originally held in August 1914. A typical sign of the “Aut” signatory series is that every recording is made up of passages taken from famous speeches or lectures already given. The time lapse between a speech being held and it being recorded ranged from only a few days to four years. A further characteristic of this “Aut” signatory is that the speaker signed the wax matrix after the successful recording.

Special status was given to the record “Aut 0” used only within the collection. This particular recording which contains the voices of both Doegen and Darmstaedter appears in none of the documents in the archive and was only discovered among the 7500 records during a review of the contents of the collection. In this recording Doegen and Darmstaedter set out their reasons for building the collection and also discuss the financial support given. The “Aut” signatory was discontinued in 1924 because Darmstaedter withdrew his financial support.

When Doegen became director of the Lautabteilung in 1920 he remained accountable to the Sound Commission (Lautkomission) which, just like the Phonographic Commission, decided on what recordings were to be made, and it was made up, in part, of the same group of people. As director of the collection Doegen was responsible for the technical realisation, conservation, and evaluation of the collection, as well as making it available to the public.

The recordings of the Lautabteilung were given the signature LA. The range of themes covered in the collection was greatly extended. Apart from “Languages and Music from around the World” (Sprache und Musik sämtlicher Völker) the documentation of German dialects became a matter of interest. Recordings of the 40 Wenker Sentences (40 Wenkersche Sätze) for the German language atlas were made with the help of Ferdinand Wrede from Marburg. Along with the various recording expeditions undertaken within Germany there were also expeditions to Switzerland, to Ireland and to Latvia. The area of recording, “Famous People”, of the “Aut” signature was carried on in the LA signature after Darmstaedter ended his involvement but this time it was developed under the title “People of Public Interest”. The voices of people included in the collection ranged from those involved in technical innovations to pioneers of aviation.

In 1925 animal noises were recorded in co-operation with the Krone circus. As well as the recordings of wild animals such as elephants, sea lions and tigers, the North American Indians who were made to put on a show by the Krone circus in the same year were brought in front of the recording trumpet. By recording the chiefs of the Iowa and Cheyenne sound documents of the Sioux and Algonquin languages were added to the collection.

When the Africanist and phonetician Diedrich Westermann took over the running of the Lautabteilung after Doegen’s dismissal in 1933, it became a teaching and research institution for phonetics and was integrated into the university[x] as the Institute for Sound Research (Institut für Lautforschung). In 1935, it was divided into departments for linguistics, music, and a phonetic laboratory. An academic specialist was responsible for each department.[xi] The archive remained in this form until 1944.

During the Second World War sound recordings were made of prisoners of war both in Germany and in camps in France between 1939 and 1941. In France there was particular emphasis on recordings of African languages. This work is not comparable with that of Carl Stumpf during the First World War either in terms of the extent or its content.

After 1945 the Institute for Sound Research was subject to much restructuring until it lost its independence in the Second Higher Education Reform of 1969, and was integrated into the section Rehabilitation Pedagogy and Communication Studies (Rehabilitationspädagogik und Kommunikationswissenschaft) as the Department for Phonetics and Science of Language (Abteilung Phonetik/ Sprechwissenschaft). Here, the Lautarchiv held a marginal position at best while the collection of material had come to a standstill considerably earlier. In 1981 it was to be disposed of altogether. But the ethnomusicologist Jürgen Elsner recognised the great value of the (for the most part neglected) collection and took steps to ensure that the collection was secured in locking rooms in the Department of Musicology (Musikwissenschaftliches Seminar). A first comprehensive report on the collection was published in 1996 by Dieter Mehnert who looked after the collection in the 1990s.[xii] Today this collection is known as the Lautarchiv and is still located at the Department of Musicology and Media Studies at the Humboldt-Universität in Berlin.

Technical and Organisational Realisation of the Gramophone Recordings in the POW Camps

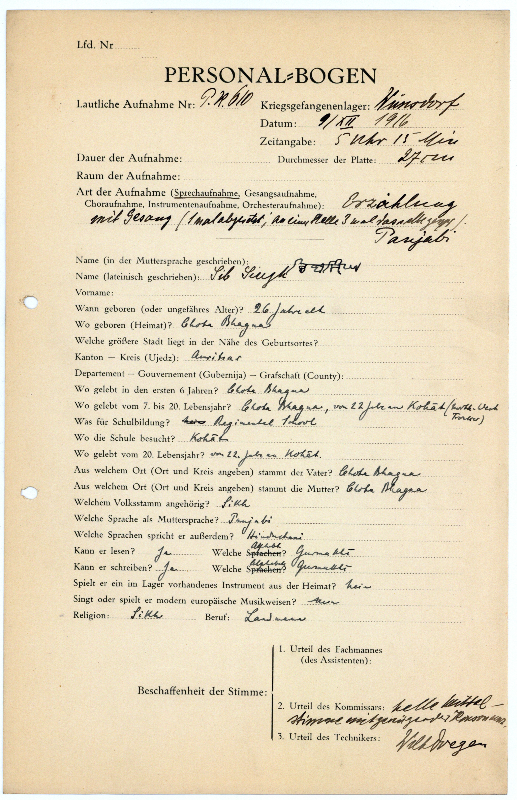

The gramophone recordings under the supervision of Wilhelm Doegen were realised in the following manner: First the members of the Phonographic Commission took account of the languages spoken by the prisoners in each camp since the lists they obtained from the camp commanders beforehand were not always accurate. The Commission and/or the language expert then decided who was to be recorded. Before each recording a so-called personal questionnaire (Personalbogen) had to be completed.

Apart from documenting the recording, the questionnaire gave detailed information about the provenance of the speaker as well as his linguistic heritage and contained questions regarding the social background of the speaker. Furthermore, no recording could be made before the text was written down in the handwriting style or typeface normally used for the speaker’s language. Since speakers and singers did not always stick to the agreed text, new transcriptions had at times to be made once the shellac discs had been produced. Transcriptions of music were only made after pressing the records.

The themes of the recordings are:

- Word groups of relatively unknown languages and containing words which are easily confused were recorded for use in dictionaries.

- Fairy tales, stories and anecdotes.

- Prisoners of war, in particular from Great Britain and France, but also from other European countries, read the Parable of the Prodigal Son (Luke XV, 11 ff.) in their own dialects. In this way dialects of all English counties were documented and could be compared with each other.

- The majority of the music recordings are vocal, only a few recordings are purely instrumental. About two thirds of the recordings are spoken and about one third is music.

The activities of the Phonographic Commission did not only extend to acoustic recordings. Apart from simply transcribing the recorded texts, so-called palatograms were made by the dentist Alfred Doegen, a brother of Wilhelm Doegen, in order to detail the exact tongue position, made more complicated by variation in accent. Xray photographs of the larynx were made to enable scientific research into specific speech sounds.

The ethnologist and curator of the Berlin Ethnological Museum, Felix von Luschan, undertook anthropological studies and made measurements of the prisoners.[xiii] A photographer took pictures of nearly every speaker and singer. About 50 of these photos survived in the archive. Not all of them can be assigned definitively to a recording. The photos show a person from the front and in profile in keeping with the contemporary ethnological practice.

There is a considerable number of African and Asian language and music recordings as well as samples of speech taken from East and West European languages. These are among the earliest sound recordings of this type. Because of their orthographic and phonetic transcriptions, accompanied by German translations, these recordings were, by contemporaneous standards, excellently documented and are therefore invaluable for current research projects. So, for example, accompanying one disc which runs for three and a half minutes there are 35 pages of written documentation.

South Asian Recordings in the Lautarchiv

Sound recordings from the following present-day states can be found in the archive: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal and Pakistan. Without exception all recordings were made using prisoners of war from the First World War as speakers and singers from the former territories of British India and Nepal. Most of these prisoners were held in the ‘Halfmoon Camp’ in Wünsdorf near Berlin.

With eleven trips, Wünsdorf was the most frequently visited camp, also known as ‘Halfmoon Camp’ (Halbmondlager) due to the large number of Muslim prisoners interned here.[xiv] Situated merely 40 kilometres south of Berlin, Wünsdorf was especially interesting for the researchers due to its rich diversity of cultures, many of which were associated with the colonial powers of England and France. About 65 idioms were classified by the members of the Phonographic Commission. South Asian Languages spoken and recorded by the interned soldiers were:[xv] Hindi/Hindustani/Urdu, Punjabi, Bengali/Sylheti, Garhwali, Old-Hindi, Baluchi, Pashto, Khasi, Limbu, Nepali, Magari, Gurung, Rai.Other languages included English (Nepal, Great Britain), Vietnamese (Vietnam), Baule (Ivory Coast), Dahomeen, Bariba (Benin), Bobo, (Burkina Faso), Mosi, Samogo (Bukina Faso, Mali),Wolof, Pulaar (Senegal), Ful (Mali, Sudan, Senegal, Guinea), Kasonke (Mali), Zarma (Mali, Nigeria), Kwa (Togo), Kru (Liberia), Malinka, Toma (Guinea), Soso (Sierra Leone, Guinea), Bantu, Swahili, Mwali, Ngazidja, Ndzwani (Comoros), Somali (Somalia), Bambara (Sudan, Mali, Senegal), Mandara, Kanuri (Sudan), Haussa (Sudan, Mali), Yoruba (Nigeria), Anyin (Ghana), Arabic, (Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco, Russian Federation), Berber (Algeria, Morocco), Kabyle (Algerien), Betsileo, Betsimisaraka, Bezanozano, Merina, Sakalave, Syanaka,Taisaka, Tanosy (Madagascar), Maltese (Malta), Tatar, Avar, Bashkir, Udmurt (Russian Federation), Kirghiz (Kyrgyzstan), New Caledonian (New Caledonia).

Adjacent to the Halfmoon Camp in Wünsdorf was the Weinberg Camp in Zossen. Here, Muslim soldiers from Russia (Tatars) were interned. In the initial phase of the recording work only seven discs were made of Tatar songs. Otherwise, all the recordings of Russian Muslims held in the Weinberg camp were made in the Halfmoon Camp. Both camps were set up to encourage the inmates to defect to the German side using carefully targeted propaganda.[xvi] We can assume that there was constant exchange of prisoners between the two camps for the recording. For instance, the Mohammedan Call to Prayer (Gebetsruf der Mohammedaner) recorded in Arabic in the Wünsdorf camp was that of a Tatar from Tobolsk who was held prisoner in the Weinberg camp.[xvii] In the Halfmoon Camp there was also a mosque with a minaret from which the muezzin could have called people to prayer.

About half of the members of the Phonographic Commission visited the Halfmoon Camp to make sound recordings. They filled 482 discs with 765 individual recordings, which accounts for approximately 30 per cent of all recordings in the archive made under the auspices of Doegen. Also relevant to the South Asian recordings is the work directed by commission members Heinrich Lüders, Friedrich Carl Andreas, Helmuth von Glasenapp, Alois Brandl and Josef Horovitz. This part of the collection comprises 282 titles on 193 shellac discs. These recordings will be examined in more detail in the following paragraph. For the most part orthographic transcriptions are available in Devanagari for all titles.

Most recordings were made by the Indian and Oriental scholar Heinrich Lüders (1869–1943)[xviii] with 150 individual recordings on 98 discs. Most of these (70 titles) are in Nepalese. lt is noteworthy that along with many Nepalese stories, Lüders also recorded songs. In the other languages, which he recorded—Gurung (23),[xix] Khasi (17), Bengali (13)—it is mostly stories which are documented, but there also neutral exemplars such as the alphabet and language samples. In the Gurung samples Lüders did not keep to the sequence of transcribing the texts and recording them for he wrote in a note attached to the translation of discs PK 636 and 637:

These examples have been recorded in a Hindi dialect, but it is not clear in which. Given the inaccurate orthography and the phonetic transcription which puts down in writing what is heard, it was no more possible for two educated Indians, whom I consulted, than it was for me to arrive at a complete translation.[xx]

With the exception of military commands (recorded by Brandl), the only recording of a South Asian POW in English camp can be found among the language recordings made by Lüders.[xxi] Disc number PK 271 is a voice recording of Ganga Ram, a Prisoner of War from Nepal. What is unusual about this disc is that he does not speak in his mother tongue, Khasi, but relates the story of the Prodigal Son which has nothing to do with his own religious background as a Hindu.

Helmuth von Glasenapp (1891–1963),[xxii] a scholar of religion and Indian studies who worked for the propaganda wing of the overseas agency Information Bureau for the Orient (Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient), made 56 discs with 86 titles. He focussed on the languages Punjabi (34), Hindi (49), Old Hindi (2) and Garhwali (1) and his work is dominated by songs more than stories or poems. The Orientalist Josef Horovitz (1874–1931)[xxiii] was responsible for 22 discs comprising 26 recordings. His recordings of Hindustani (21) and Belutschi (5) consist mainly of stories—especially fairy tales and anecdotes. Nine of 16 recordings made by the Orientalist and Iran scholar Friedrich Carl Andreas (1846–1930)[xxiv] are recordings of Pashto songs on shellac discs. Comic songs make up a significant part of his list of recordings. Alois Brandl,[xxv] philologist and Professor for English at Berlin University made only four recordings of Indian prisoners of war on four discs. His other 260 titles made for the Phonographic Commission are of acoustic signals with a bugle and English military commands. At this point it is also necessary to mention the recordings of Georg Schünemann. On his list of recordings from the prisoner of war camps the following can be found: 16 Ghurkha, four Sikh, seven Thalor and one Hindustani.[xxvi]

The content of even the strangest of these recordings is noted in neutral terms by the commission. One of the four Punjabi stories recorded by Glasenapp is directly related to a wish on the part of the prisoners relating to the camp and the religious attitude of the Sikhs. Tue disc numbered PK 676 was made by Sundar Singh on 5 January 1917 under the general title “Story” (Erzählung). In order to criticise the attitude of the camp authorities to the religious sensitivities of the Sikhs, he praises the living conditions in the camp in an exaggerated way:

Om, by the grace of the true guru (or: the Granth). The guru has looked upon us with great benevolence for he has revealed himself in this strange land and in this captivity and in this very prison. We are so happy that we feel blessed. To us, there can be no bliss greater than this, it is greater even than the bliss of peace. Due to this the religious assemblage has succeeded. We regard the Granth Sahib as the likeness of the tenth Guru and highly venerate it. If anybody should not venerate it or should not be willing to venerate it then each and every Singh would be prepared to sacrifice his life at this place or he would not suffer to have it [the Granth] dishonoured. So far our Guru Saheb [i.e. the Granth] has not received a blanket. If we had been in India and our Guru Sahib had gone without a blanket, we would not have taken any food. We have tried a lot but our Guru Sahib has not received a blanket yet. If we were not to take any food in this place we would perish very quickly because we have no strength left in our bodies for you know that these (people) do not receive food like they do in India. Therefore, we cannot give up taking food. That the English have sent us our Guru Granth Sahib—of what avail is that? Think about this yourself and swiftly furnish us with a reply.

When we see the denizens of Germany we feel very happy, but we believe that the Germans do not think of us as we do of them. If the Germans thought of us like this, they would honour the house [i.e. the temple] of our guru [i.e. the Granth].

PS: Refers to the desire of the prisoners to obtain a blanket for their holy book, the ‘Granth’.[xxvii]

Criticism on the situation in the camp was not always passed so openly. The difficult life of the prisoner also finds expression in the form of fables, fairy tales or anecdotes. The following example, also recorded by Glasenapp can be interpreted in this way:

A peasant was friends with a tiger. The friendship between them was very great. One day the tiger came to the house of the peasant. The wife of the peasant said: ‘You have made friends with jackals, wolves and tigers, don’t you have any shame? Since the tiger has been coming to our house, there is a stench in the house.’ When the tiger heard this, he was enraged and left the house. The peasant left with him. The tiger said to the peasant: ‘You are only my friend if you strike at my head with an axe.’ On hearing this, the peasant complied with his wish and struck with the axe, then the tiger abandoned him. When, after one year, the tiger met the peasant again, the tiger said: ‘Now look at the wound of the axe with which you have struck at my head.’ When the peasant looked for the wound, no wound was there. The tiger said: ‘The wound caused by the axe has vanished, but what your wife has said that is a wound I will carry for the rest of my life. Now the friendship between us is at an end.’ Take a good look, my friend, this address even an animal has not forgotten, how could a man forget the like?[xxviii]

Regardless of whether the recording is of a traditional story or one which has its origin in the camp, the real issue is that the context always remains that of a prisoner of war camp. If we accept this as a basis for our interpretation, Ishmer Singh, herein the role of the tiger, can be seen to give expression to wounds he received in the war and as a prisoner which are not visible on the surface.

The palatogram and X‑ray images mentioned earlier were not the only pieces of research in the area of physical anthropology. The prisoners of the Halfmoon Camp were often the subjects of anthropological examinations. On the invitation of Felix von Luschan (Royal Ethnological Museum in Berlin and Professor of Anthropology at Berlin University) the Austrian Rudolf Pöch and his assistant Josef Weninger carried out examinations of West African prisoners which were only published in 1927 in Vienna.[xxix] Pöch also carried out much wider research on Austrian and Hungarian prisoners of war which should be considered in conjunction with the data from the Halfmoon Camp. Egon von Eickstedt, a pupil of Luschan, made head measurements of Sikhs and tried to establish a topology, but his experiment failed.[xxx]

lt is noteworthy that the documentation provided by the Phonographic Commission in no way attempted to convey anything of the individuality of each person. The personal record cards tell us nothing about the family background of the prisoner, nor the circumstances in which he came to be involved in the war. The personality of each prisoner was only used to place them in a socio cultural matrix. The purpose of the personal details was to allow the prisoner to be grouped according to ethnicity and language. Any information beyond this was of no interest to the Phonographic Commission. It was not seen as an omission that the recordings were made without a cultural context. This weakness in the strategy used for collecting data can be linked to the political situation at that time. By way of their documenting of languages and styles of music, the Phonographic Commission sought to meet the demands made on them by a colonial power. In this way the global cultural interests of Germany and their claims as a colonial power could be reinforced. Doegen was not only pursuing a personal interest in creating a sound recording archive; he was also keeping an eye on other more commercial purposes. For example, the recordings were to be used for training colonial officials in the languages of the colonies envisioned as of strategic importance after a successful conclusion of the First World War from the point of view of the German Empire.

As a general rule, the notebooks accompanying the shellac discs of the sound recording archive in which the phonetic and orthographic transcription of the contents of each disc held in printed form give no details about the personal life of the prisoner because of the nature of the personal information given. These books do not give the reader any sense that the recordings were made in prisoner of war camps.[xxxi] Nor is there a notebook accompanying the South Asian recordings for only a small number of these discs must have been sold. The researchers did not use the South Asian material for their publications.

These examples should demonstrate the type of absence of information in the archive. On the other hand, there is no other historical sound archive of that status. And even if the information is not complete at least the Lautarchiv provides a base that allows us to continue searching for descendants and further information. Therefore research in this archive can help in shifting the focus away from seeing the war through the lens of interactions among states and towards individual trajectories.

In 1925 Alois Brandl writes about the quality of the recordings of British dialects made by him in the prisoner of war camps:

Reviewing the material I collected in 15 camps, from a summary study of some 1000 speakers of dialects and from a close sounding out of 75, underneath all the variegation there is a unifying characteristic: it is not taken from books or newspapers but from real life.[…] Here resounds a choir of participants in the war, whose voices otherwise would have faded away; a hundred years from now they shall still speak as that portion of England’s soul which, in critical times, had to act and endure but did not have a say in public. Good lads, how unflaggingly have you repeated your couple of lines until they were incorporated into the museum of linguistics! […] One day the better England[…] will awaken once more and honour this cultural work amidst the incessant clamour of weapons in world history; until then let it stand in the shadow as mere ‘dialectology’, as bizarre philologism, as German reverie.[xxxii]

Of all the scholars named above who made recordings of soldiers from southern Asia in the Halfmoon Camp, Alois Brandl, along with Heinrich Lüders,[xxxiii] is the only person to make reference to the research and recordings in the prisoner of war camps in his article in Doegen’s book “Amongst Foreign Peoples” (Unter fremden Völkern) published in 1925. The three essays written by Helmuth von Glasenapp, which are published in this book, refer neither to the circumstances of the recordings nor to his own recordings.[xxxiv] Josef Horovitz refers to his work in the camps only in the last paragraph of his article entitled “On Indian Muslims”.[xxxv] The essay by Friedrich Carl Andreas makes no mention of his visits to the prison camps.[xxxvi]

Conclusion

An unusual source is available to those who wish to investigate the situation of South Asians who were detained in German internment camps during the First World War. An acoustic document, the shellac disc, offers information of a very particular type. Despite the crackling these recordings give a sense of immediacy created not least by the recording techniques used from the beginning of sound recording. In this way sound documents of many peoples have been preserved and are today stored in the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. The sound documents are part of a world heritage and offer linguists, historians as well as scholars of cultural and literary studies from all parts of the globe an invaluable corpus of research material.

It is now more than 90 years since the beginning of the First World War. This distance should allow for this collected material, which is not only a multilingual repository of recorded language samples but an important part of world cultural heritage, to be evaluated and analysed more comprehensively and from various academic angles. This research should be carried out by academics from the respective linguistic regions for they are best placed to unravel the various phonetic, semantic, and pragmatic levels of the acoustic material and set them in their appropriate cultural and historic context.

In recent years the documents of the sound recording archive have been the basis of exhibitions and documentary films. In terms of the South Asian recordings Philip Scheffner’s film and exhibition project “The Halfmoon Files” is worth mentioning. The basis of his research is the voice recordings of British-Indian soldiers kept in the archive.[xxxvii]

The re-recording of the main part of the shellac disc collection from the years 1915–44 was concluded with the creation of the data base in 2005. The digital files of the 3825 discs are now available in WAV format and as MP3 files. As there was often more than one recording on each side of a disc, a total of 6806 files were created. Because of the level to which individual recordings have been developed the sound recording archive has set international standards for similar sound collections.

Endnotes

[i] http://www.sammlungen.hu-berlin.de, Rev. 2011-02-14. At the moment the webpage can be accessed in German only. Since the database comprises a variety of other collections researchers are advised, in order to exclusively search the sound archive, to choose under the option “Thesaurus” “Sprachen” (languages) or “Sprachfamilien” (families of languages). Due to copyright issues the online version of the database does not include the option of listening to the actual sound files. Titles and various information about each recording is available however.

[ii] Doegen,Wilhelm (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 9. The modern collection corresponds to Doegen’s classification, yet the starting dates of the different branches vary: from 1915 Languages, Music and Songs of the Peoples of the World (Sprachen, Musik und Gesang der Völker der Erde), from 1917 Vocal Potraits of lmportant Public Figures (Stimmportraits bekannter Persönlichkeiten) and from 1922 German dialects (deutsche Mundarten) as well as “Miscellaneous” including animal voices.

[iii] Carl Stumpf founded the Phonogramm-Archiv at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in 1905 with audio recordings that he had been producing since 1900 on Edison wax cylinders. The Phonogramm-Archiv now is part of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. Simon, Arthur (ed.) Das Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv 1900–2000—Sammlungen der traditionellen Musik der Welt, Berlin: Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 2000, S. 25–46.

[iv] All the figures quoted are based on the documentation of 1650 shellac recordings of the Phonographic Commission, today held by the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt University of Berlin.

[v] Simon, Ibid., S. 237. The shellac discs of the Phonographic Commission carry the signature “PK”, whereas that the Edison wax cylinders have the signature “Phon. Komm.” The shellac disc, which in comparison to wax cylinders (or phonograph cylinders) is marked by a better playback quality, reproducibility, and durability, was to be used as a new medium of teaching. The content of the wax cylinders is not part of this article.

[vi] This was based on Doegen’s “memorandum on the establishment of a sound department in the Prussian state library” (Denkschrift über die Errichtung einer Lautabteilung in der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek).

[vii] Geheimes Staatsarchiv—Preußischer Kulturbesitz [GStAPK), number 250,Vol. I, documents 78 and 79. Following a meeting of the Phonographic Commission on 3.2.1919, Carl Stumpf wrote to the Ministry for Education on 12.04.1920 as follows: “Sie [die Kommission] kann daher ein starkes Befremden darüber nicht verhehlen, dass im Staatshaushaltsplan von 1920 zu diesem Zwecke die Errichtung einer Lautsammlung als besonderer Abteilung der Staatsbibliothek vorgesehen ist, ohne dass die Meinung der Phonograpischen Kommission irgendwie gehört worden wäre.”

(“We [the Commission] cannot withhold our reservations about the national budget plan of 1920 envisaging the establishment of a sound collection as a special department of the state library, without in any way hearing the opinion of the Phonographic Commission.”)

[viii] GStAPK, number 250, Vol. I, documents 3 and 4. Contract dated 17.03.1917.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] The Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin has been renamed several times. To avoid confusion here are the names in chronological order:

1810–1827 Berliner Universität, 1828–1945 Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, 1945–1947 Universität Berlin, 1948-today Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

[xi] D. Westermann took over the running of the department of linguistics, F. Bose that of music and F. Wethlo the phonetic laboratory.

[xii] Mehnert, Dieter, „Historische Schallaufnahmen—Das Lautarchiv an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin“, Studientexte zur Sprachkommunikation 13 (1996): S. 28–45.

[xiii] Lange, Britta, “South Asian Soldiers and German Academics: Anthropological, Linguistic and Musicological Field Studies in Prison Camps”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), ‘When The War Began We Heard of Several Kings’ South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 149–185.

[xiv] In a mosque specially built for the prisoners they could congregate for prayers. The call of the muezzin has been preserved on the shellac discs. Apart from the shellac discs several photographs depicting the camp life have been preserved (Cf. Kahleyss, Margot, Muslime in Brandenburg—Kriegsgefangene im 1. Weltkrieg: Ansichten und Absichten, Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2000), see also Kahleyss, Margot, “Indian Prisoners of War in World War I: Photographs as Source Material”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), Ibid., pp. 187–206. Even a short film documentation from the camp exists (kept in the Bundesfilmarchiv). Madhusree Dutta and Philip Scheffner used this material as well as recordings from the Lautarchiv in their documentary “From Here to Here” dealing with Indo-German relations (lndia, 2005, 58 min.). The film scene from the camp can also be found in Scheffner’s latest documentary: “The Halfmoon Files”.

[xv] Inside the brackets are the names of present states.

[xvi] Liebau, Heike, “The German Foreign Office, Indian Emigrants and Propaganda Efforts Among the ‘Sepoys’”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), Ibid., pp. 96–129 and Liebau, Heike, 2011, “Hindostan: A Camp Newspaper for South-Asian Prisoners of World War One in Germany”. In: Ibid., pp. 231–249.

[xvii] The disc’s signature is LA, PK 626.

[xviii] Heinrich Lüders was an Orientalist and Indologist. From 1909 he was the chair of languages and literature of Ancient lndia at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität as well as being, also from 1909, member of the Prussian Academy of Sciences. 1931–1932 he acted as principal of the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität in Berlin. For further details on Lüders, cf. Lange, Ibid.

[xix] The numbers in the brackets gives the amount of individual titles in the respective language.

[xx] Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Lautarchiv, folder No. 9. “Die Stücke sind in einem Hindi-Dialekt abgefaßt, doch ließ sich nicht feststellen in welchem. Bei der fehlerhaften Orthographie und der nach dem Gehörten wiedergegebenen phonetischen Umschrift war es zwei von mir herangezogenen gebildeten Indern ebenso wenig als mir selbst möglich, eine vollständige Übersetzung herzustellen.”

[xxi] Other languages documented by Lüders: Limbu (6), Hindi (5), Pashtu (4), Hindustani (3), Magar (3), Urdu (2), Rai (1), Gurmuk[h]i (1), Magari (1).

[xxii] Glasenapp was Professor of lndology at the University Königsberg (East Prussia, 1928–44), Professor of Comparative Religious Studies at the University Tübingen (1946–59). During the First World War Glasenapp was a member of the NfO.

[xxiii] Horovitz was from 1902 lecturer at the University of Berlin, between 1907–14 lecturer in Arabic at the Muhammedan Anglo-Oriental College in Aligargh, lndia. From 1915 to 1931 he held the chair in Semitic languages at the Oriental Seminar of the University Frankfurt am Main.

[xxiv] Andreas was from 1883 to 1903 Lecturer of Persian and Turkish at the Oriental Seminar of the University of Berlin. Since 1903 he held the chair in West Asian Languages at the University Göttingen.

[xxv] Subsequent to holding chairs at Prague, Göttingen and Strasbourg, Brandl, in 1895, became professor of English Philology in Berlin.

[xxvi] List “Sammlung aus den Kriegsgefangenen-Lagern” (Collections from the prison camps) in: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin—Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Ethnologisches Museum. No inventory number.

[xxvii] “Om, durch die Gnade des wahren Guru. Der Guru (oder: der Granth) hat mit großer Güte auf uns geblickt, denn er hat sich uns im fremden Lande und in dieser Gefangenschaft und uns diesem Gefängnis gezeigt. Wir sind so glücklich, daß wir selig sind. Es kann kein größeres Glück für uns geben, als dieses; es ist größer als selbst das Glück des Friedens. Die religiöse Versammlung ist dadurch glücklich. Wir betrachten den Granth Sahib als das Ebenbild des 10. Gurus und verehren ihn sehr. Wenn irgendeiner ihn nicht ehrt, oder ihn nicht ehren will, so wird jeder Singh bereit sein entweder an diesem Ort sein Leben zu geben, oder wird es nicht dulden ihn [den Granth] entehrt zu lassen. Bis jetzt hat unser Guru Saheb [d.h. der Granth] keine Decke erhalten. Wären wir in Indien und hätte unser Guru Sahib keine Decke, so würden wir keine Speise zu uns genommen haben. Wir haben viel versucht, aber unser Guru Sahib hat bis jetzt noch keine Decke erhalten. Wenn wir an diesem Ort keine Speise essen würden, so würden wir sehr schnell sterben, weil in unseren

Körpern keine Kraft ist, denn Sie wissen, dass diese (Leute) kein Essen wie in Indien erhalten. Deshalb können wir das Essen nicht aufgeben. Daß die Engländer uns unseren Guru Granth Sahib gesandt haben, was hat das für einen Zweck? Denken Sie selber über diese Sache nach und geben Sie uns schnell Antwort. Wenn wir die Bewohner Deutschlands sehen, sind wir sehr glücklich, aber wir glauben, dass die Deutschen von uns nicht so denken, wie wir von ihnen. Wenn die Deutschen so dächten, so würden sie das Haus [d.h. den Tempel] unseres Gurus [d.h. des Granth] ehren. P.S. Bezieht sich auf den Wunsch der Gefangenen, für ihr heiliges Buch, den ‘Granth’ eine Decke zu erhalten.” Cf. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, LA, folder No. 9. All the notes in brackets are in accordance with the original.

[xxviii] Recording of Isher Singh on the 11 December 1916. The translation of PK615 exists in the form of a typescript. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, LA folder No 9.

[xxix] Lange, Britta, “Academic Research on (Coloured) Prisoners of War in Germany, 1915–1918”. In: Dominiek Dendooven and Piet Chielens (eds), World War 1. Five Continents in Flanders, Tielt: Lanoo, 2008, pp. 153–159.

[xxx] Eickstedt, Egon von, „Rassenelemente der Sikhs“, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 52 (1920–21): S. 317–394.

[xxxi] Lautbibliothek-Phonetische Platten und Umschriften (published by Lautabteilung der Preussichen Staatsbibliothek), 1926–1930.

[xxxii] Brandl, Alois, „Der Anglist bei den Engländern“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Ibid., S. 362–376, see S. 375f.

[xxxiii] Lüders, Heinrich, „Die Gurkhas“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Ibid., S. 126–139.

[xxxiv] Glasenapp, Helmuth von, „Der Hinduismus“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Ibid., S. 116–125; Idem, „Die Radsehputen“. In: Ibid., S. 140–150; Idem, „Die Sikhs“. In: Ibid., S. 151–160.

[xxxv] Horovitz, Josef, „Die indischen Mohammedaner“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Ibid., S. 161–166.

[xxxvi] Andreas, Friedrich Karl, „Iranier“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Ibid., S. 376–383.

[xxxvii] The film had its world premiere at the 57th Berlinale film festival during The International Forum of New Cinema on 16 February 2007. Several international awards followed. http://www.halfmoonfiles.de, accessed on 25.05.2023.

Bibliography

Andreas, Friedrich Karl, „Iranier“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 376–383.

Brandl, Alois, „Der Anglist bei den Engländern“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 362–376.

Doegen, Wilhelm (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925.

Eickstedt, Egon von, „Rassenelemente der Sikhs“, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 52 (1920–21): S. 317–394.

Glasenapp, Helmuth von, „Der Hinduismus“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 116–125.

——–, „Die Radsehputen“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 140–150.

——–, „Die Sikhs“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 151–160.

Horovitz, Josef, „Die indischen Mohammedaner“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 161–166.

Kahleyss, Margot, Muslime in Brandenburg—Kriegsgefangene im 1. Weltkrieg: Ansichten und Absichten, Berlin: Staatliche Museen Preußischer Kulturbesitz, 2000.

——–, “Indian Prisoners of War in World War I: Photographs as Source Material”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), ‘When The War Began We Heard of Several Kings’ South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 187–206.

Lange, Britta, “Academic Research on (Coloured) Prisoners of War in Germany, 1915–1918”. In: Dominiek Dendooven and Piet Chielens (eds), World War 1. Five Continents in Flanders, Tielt: Lanoo, 2008, pp. 153–159.

——–, “South Asian Soldiers and German Academics: Anthropological, Linguistic and Musicological Field Studies in Prison Camps”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), ‘When The War Began We Heard of Several Kings’ South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 149–185.

Liebau, Heike, “The German Foreign Office, Indian Emigrants and Propaganda Efforts Among the ‘Sepoys’”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), ‘When The War Began We Heard of Several Kings’ South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 96–129.

——–, “Hindostan: A Camp Newspaper for South-Asian Prisoners of World War One in Germany”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau and Ravi Ahuja (eds), ‘When The War Began We Heard of Several Kings’ South Asian Prisoners in World War I Germany, New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 231–249.

Lüders, Heinrich, „Die Gurkhas“. In: Wilhelm Doegen (Hg.), Unter fremden Völkern. Eine neue Völkerkunde, Berlin: Otto Stollberg, 1925, S. 126–139.

Mehnert, Dieter, „Historische Schallaufnahmen—Das Lautarchiv an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin“, Studientexte zur Sprachkommunikation 13 (1996): S. 28–45.

Simon, Arthur (ed.) Das Berliner Phonogramm-Archiv 1900–2000—Sammlungen der traditionellen Musik der Welt, Berlin: Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung, 2000.

Jürgen‑K. Mahrenholz, Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Nico Putz, Paula Schnabel, Jannes Thode

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029