By Markus Schlaffke & Isabella Schwaderer

Published 2021

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00030

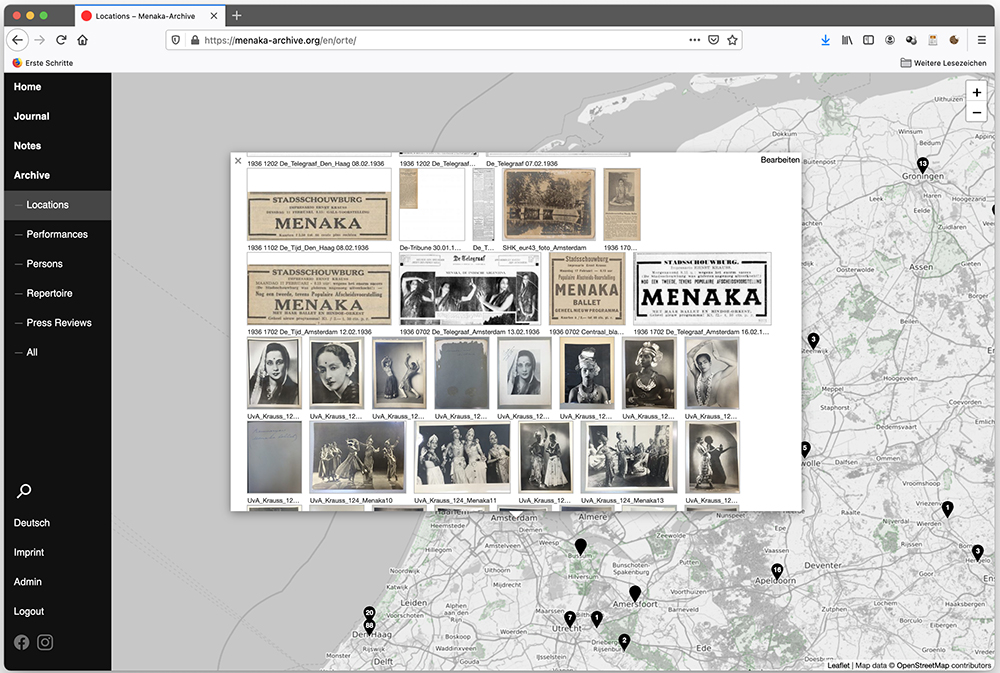

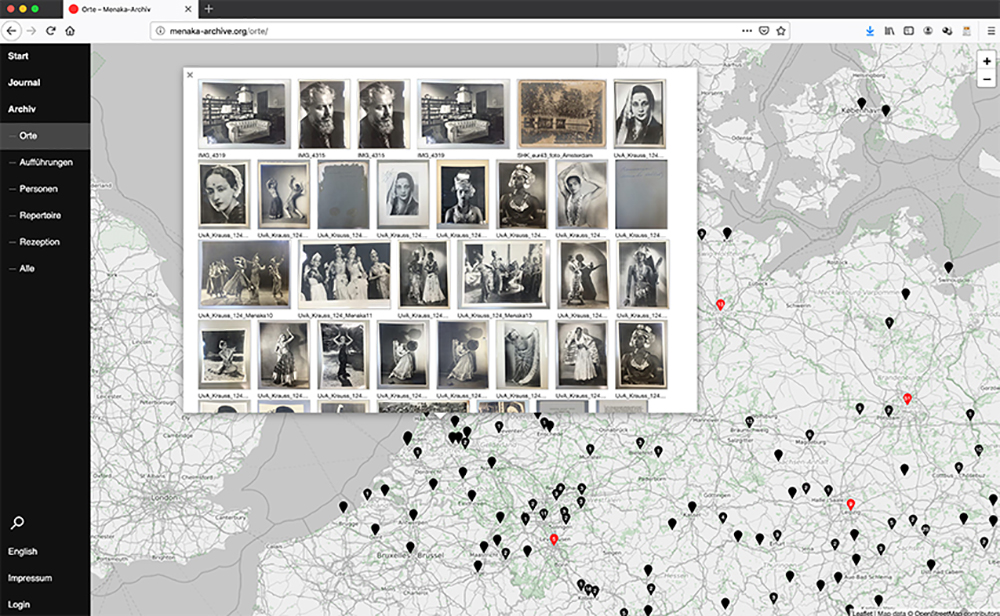

Image: A screenshot of the Menaka digital archive’s locations interface, which enables the user to trace sources on a world map.

Table of Contents

Towards the Digital Archive | Transnational Sites of the Archival Sources | Engaging critically with the Source-Base | The Menaka-Archive as Collaborative Research Platform | Endnotes | Bibliography

photo: Allard Pierson Collections Amsterdam,

https://allardpierson.nl/collecties/.

The Menaka-Archive (www.menaka-archive.org) is a digital meta-archive which houses and links documents on the Indian dancer and choreographer Leila Roy-Sokhey, alias Madame Menaka. The focus of the digital collection is on material from the context of the three-year tour that Leila Roy undertook with her Indian ballet through Europe and especially through Germany from 1936–38. In this paper, we describe the structure of the digital Menaka-Archive and some of the methodological approaches we have been exploring in researching, indexing, describing, and contextualizing its collection.

Madame Menaka was the stage name of the Bengali dancer and choreographer Leila Roy-Sokhey (1899–1947). In the 1920s and 30s, Leila Roy was active in India’s national cultural reform. She strove to revitalize traditional dance forms such as the North Indian Kathak, founding her private dance school and ensemble, for which she choreographed dance dramas. Already in the early 1930s, she undertook tours both in South Asia and Europe. Her project received international attention on a larger scale when she toured Europe for the second time with her ensemble from 1936 to 1938. Most of this tour took place in Germany, where the Menaka Ballet also performed at the international dance competitions during the Olympic Games in Berlin in the summer of 1936.

These are some of the milestones of an artist’s life trajectory, which quite literally crisscrossed with conflict-ridden spaces across Europe and India – both geographically and metaphorically. Menaka’s body of work is considered one of the first internationally recognized attempts at staging and establishing contemporary Indian dance. It aimed to be accepted both creatively and theoretically on a par with the Western avant-garde. At the same time, it also sought to emancipate itself from the hegemonic power of the European art world to develop an independent and „nationally authentic“ artistic language.

In Indian art history, Menaka’s work is acknowledged as a contribution to the revitalization of the north Indian Kathak-dance. Above all, however, Menaka is known for her merit in opening up the highly controversial field of dance for a new middle class, freeing it from longstanding social stigma and therein connecting it to the emerging nationalist movement in India. The dance steps of the Indian ballet were seen as essential steps towards strengthening national self-confidence in India and thus part of broader critical discourses on British colonial rule (Kanhai 2020).

photo: Allard Pierson Collections Amsterdam,

https://allardpierson.nl/collecties/

Meanwhile, in Europe, the idea of national cultural renewal, prominently featuring in Menaka’s Indian Ballet, was compatible with social-revolutionary discourses and aesthetical utopias. Especially in Germany, the Indian Ballet provided a particular „platform in projecting modern longings for a return to the origins.“ (Baxmann 2008a: 42).[i] Particularly in the 1930s, dance performances from Asia met with widespread interest because they „seemed to refer to bodily knowledge that had been lost in Europe.“ (Ibid.) Such considerations were a pan-European phenomenon, but in Germany they lead to an almost “inevitable” amalgamation of folklore and racial ideology (Baxmann 2008b: 102). During the three-year tour of Menaka’s Indian Ballet, the National Socialist cultural policy was being consolidated. Unintentionally, the Indian artists provided ample illustrative material for an ongoing quest of German society for „re-rooting“ national culture in Germany based on racializing principles.

Both in Europe and India, the Menaka Indian Ballet has left its mark on the artistic landscape. However, compared to the extent of its contemporary reception, remarkably little of Leila Roy’s project has been archived. There is no Menaka archive in India. Leila Roy died relatively young at the age of 48 in 1947 from Bright’s disease, a chronic liver disorder. Her private dance studio (first on the campus of the Haffkin Institute in Bombay, later in Khandala, a suburb of Bombay) could no longer exist in the professional form she had envisaged for it, already by the early 1940s and closed down after her death. The dancer Damayanti Joshi, trained by Leila Roy, also participated in the Menaka Ballet’s European tour. Later in her life, she published a short biography of the artist in 1989 (Joshi 1989). Until today, this is the only comprehensive witness account of Leila Roy’s life and body of work by one of her contemporaries.

Nevertheless, the performances of the Menaka Ballet, albeit fragmented, have been widely documented. Newspaper reports, theatre programs, photo collections, letters, film clips and sound recordings paint a nuanced picture of the dance events. Especially the European tour of 1936–38 was a thoroughly documented event. Not only does it offer material related to the hundreds of performances done by the ensemble over three years, but it also points to transnationally interwoven art-worlds and their underlying ideological and logistical networks during the inter-war period.

This material and its discursive field were the starting point for the idea of a digital Menaka-Archive. The archival research project aims to understand the three-year European tour of the Indian Ballet as an archive in its own right, to collect traces of the dance performances, locate fragmented archival holdings, link them in a database, and map the overall event of the tour. This growing database of a transnational art event such as the Menaka tour promises new insights providing the basis for further inter-disciplinary research.

Towards the Digital Archive

The first impulse for a systematic reconstruction of the Menaka tour came from our Indian partner, Ustad Irfan Muhammad Khan, a musician working in Kolkata. Since his grandfather, Sakhawat Hussein Khan, had participated as a musician in the Ballet’s European tour, he asked for help with his research into his family history in Germany. In return, Irfan Khan opened his family archive with his grandfather’s memorabilia in Kolkata for access.

In 2015, the exchange with Irfan Khan first led to a series of joint artistic events with music, Kathak dance performances and short lectures on the historical classification of the programme in Germany. At the same time, initial research in German archives brought first results and led, subsequently, to ideas to systematize the growing collection of found objects via an archival concept. Since 2016, the project has taken concrete shape within Markus Schlaffke’s PhD project (Schlaffke 2021).

This project was part of the doctoral program for artistic research at the Bauhaus-University Weimar and connected artistic/design practice and cultural studies research. The construction of the database, the conceptualization of interfaces and the further development and curation of the digital archive was first understood and described here as a specific form of artistic research.

From 2018, Isabella Schwaderer has systematically located and compiled the reviews of all documented Menaka performances in German regional newspaper archives and from international digital archives for her research on the Menaka Ballet’s reception history in the context of her postdoctoral project based at the Chair of General Religious Studies at the University of Erfurt. The theatre reviews provide a text corpus, which is part of her broader research on the image of India in the German debate around German religious reform movements across art and philosophy.

As a database and website interface, the archive has existed since 2019. We have been running the website with a connected research blog, expanding the collection and developing new material. The archive has changed from the original intention of simply documenting the German tour of the Indian Ballet as completely as possible to a broader approach of bringing diverse materials from other European countries and India together on the early and late history of Menaka’s artistic work.

In the following sections, we provide an overview of the several sites where we found sources related to the ensemble’s trajectory and discuss some methodological considerations for further exploration. All sources have duly been listed and described in the digital Menaka-Archive.

Transnational Sites of the Archival Sources

1. The Ernst Krauss collection in The Allard Pierson Collections, University of Amsterdam

photo: https://allardpierson.nl/collecties/.

Allard Pierson collections Amsterdam, https://allardpierson.nl/collecties/.

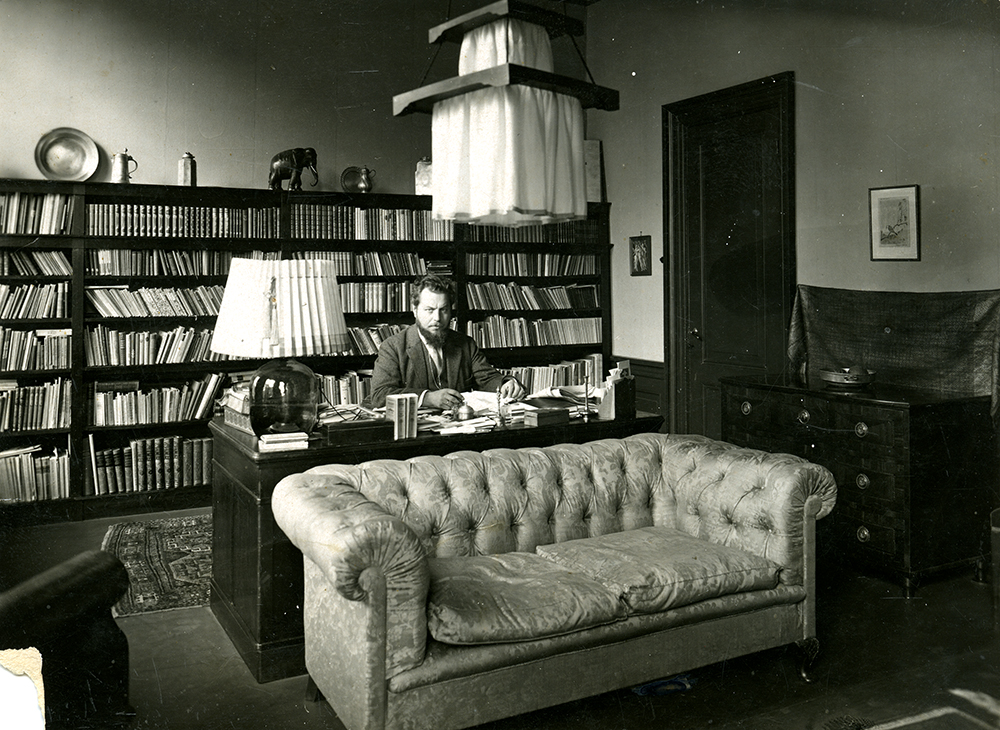

The lack of scholarly publications and edited sources on the history of Menaka’s Indian Ballet makes the reconstruction of her European tour an archival detective work. The increasing move towards digitization of archives constantly changes this situation. However, as recently as 2016, at the beginning of the authors’ research, searches in the databases available online yielded virtually no results. The identification of the personal collections of Ernst Krauss, the impresario of the Menaka tour, in the Allard Pierson Collections, University of Amsterdam (https://allardpierson.nl/en/), therefore, was a breakthrough for the research.

Ernst Krauss (1887–1958) was a German who had established an artists‘ and concert agency with an international reach in Amsterdam in the 1920s. Krauss had planned, coordinated, and financed the majority of Menaka performances in Europe since 1935. Extensive material from his agency – primarily artist portfolios, event documentation, and some personal papers – are preserved in the Allard Pierson Collections’ theatre archive. As Krauss had no children, the records of his company and private documents went to the Allard Pierson Collections. The collections were catalogued in the early 1990s, and this allowed us to identify the Krauss estate. It also contains a portfolio with promotional material, photographs, reviews and, most importantly, a list of documented performance dates and venues of the Indian Ballet in Germany. This list was an important clue for assessing the scale of the tour and creating a grid for further systematic research.

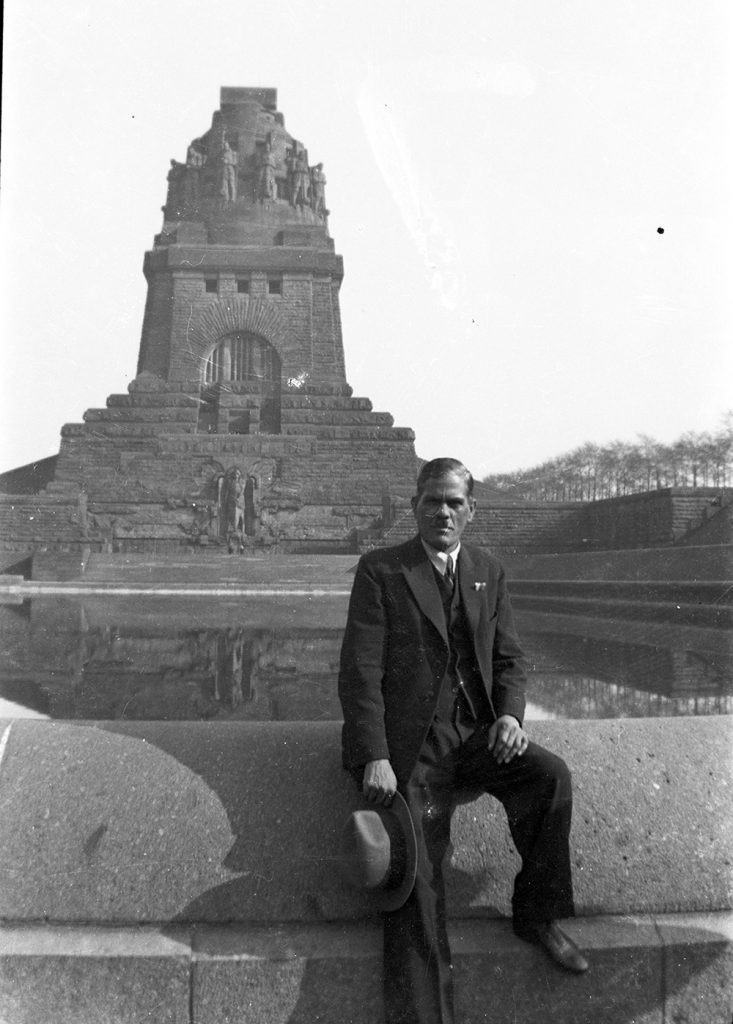

2. The Khan Family Archive, Kolkata

Another important source of information is the private archive of the Khan family of musicians in Kolkata. This consists of the private collections of Sakhawat Hussein Khan, who led the six-member accompanying orchestra of the Menaka Ballet. Khan regularly wrote letters from Europe, reporting about his experiences, settling family matters. He also documented his journey with his camera. The albums with photographs showing his travels through Germany, his postcards, letters, and souvenirs have been kept by Sakhawat Khan’s grandson Irfan Muhammad Khan. These documents represent a coherent collection of sources that visually depict the Menaka tour from the perspective of one of its participants.

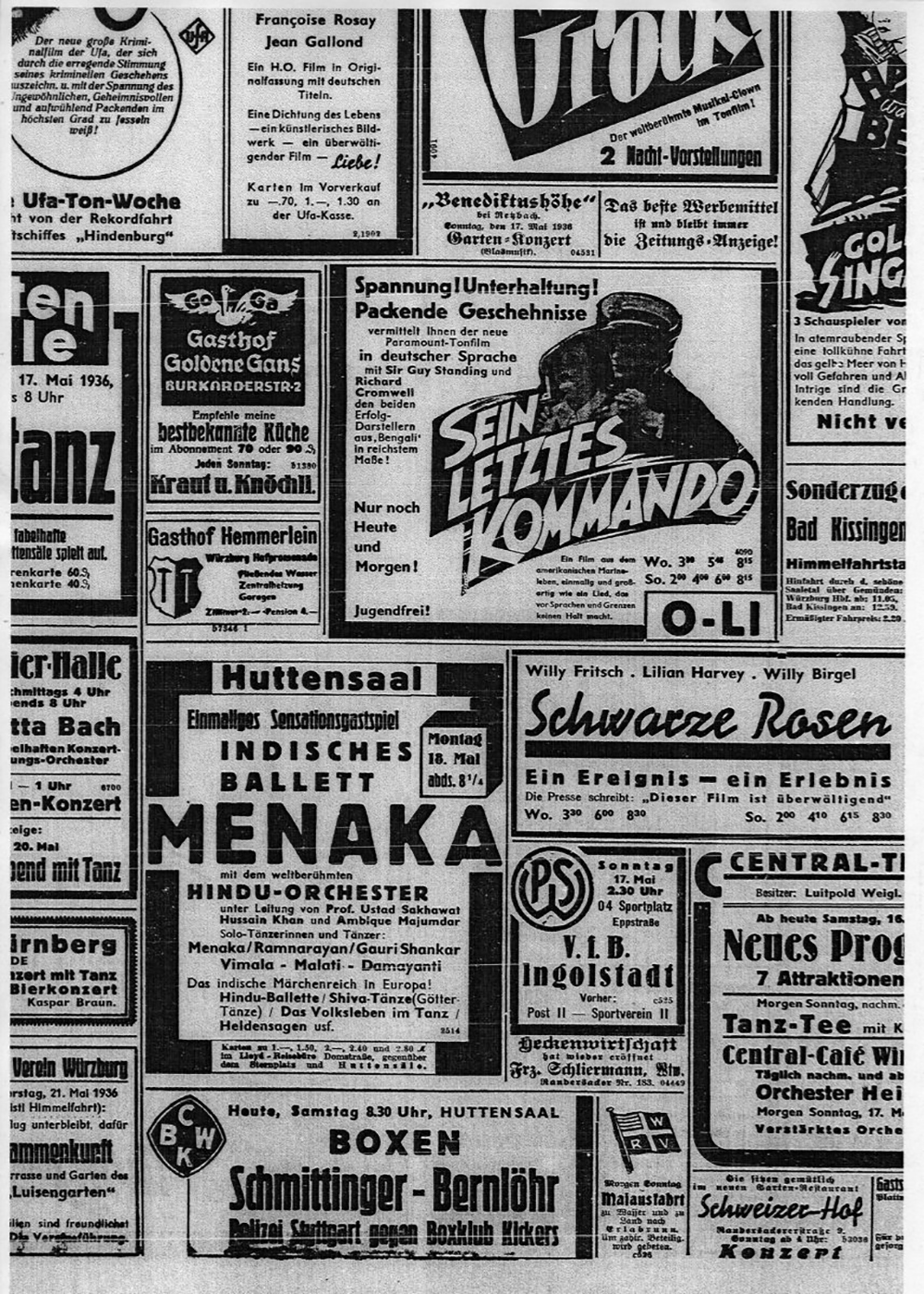

3. The European Press Archive

The performances of the Menaka Ballet have been extensively documented in European press. These took place almost every evening on the stages of hundreds of different city theatres in the German-speaking countries, and beyond, and generated a broad response in the feature pages of regional newspapers. The search for the German material turned out to be comparatively complicated since at the beginning of this particular part of the research, in 2018, virtually no German newspapers were accessible in digitized form. Therefore, we had to rely on local archives of several cities (Stadtarchive), where we suspected one or more performances had taken place, based on the tour schedule. Our search in the archives bore overwhelming results in the form of numerous traces of the tour. A base of about 120 theatre reviews, generally in two columns of about 500 words, sometimes with a picture, were the starting point.

This was a much easier process when it came to the full-text searches we could conduct in the archives of neighbouring European countries, many of which have meanwhile become accessible, that led us to high-quality documentation of the tour. The following national platforms should be mentioned here, in the order in which we integrated the documents:

- Delpher (https://www.delpher.nl/): Netherlands

- Anno (https://anno.onb.ac.at/): Austrian National Library

- Digitised Swiss newspapers (https://www.e‑newspaperarchives.ch/)

- Digital archive of the French National Library (https://gallica.bnf.fr/)

- Europeana (https://www.europeana.eu/en): various European newspapers

Among the materials that have increasingly become accessible, are advertisements, theater critiques and pictures from the Singapore newspaper archive (https://eresources.nlb.gov.sg/newspapers/), which form a basis for reconstructing the Menaka Ballet’s South Asian tour in 1935. Various Indian newspapers, predominantly the Bombay Chronicle, also decisively shed light on the hitherto completely neglected area of the Indian reception of Menaka’s stage dramas.

This increasing digital availability of sources helps trace the transnational and colonial entanglements of a global entertainment industry. For instance, reports on the Indian Ballet appear in places where the troupe had never been, such as Australia. The network of news bureaus and the exchange of texts from feuilletons show that disputes about art and culture were important and were consumed internationally along with news about politics, economics, and the natural sciences.

4. Individual sources

In addition to the collections identified so far, several individual sources that are important for the collection of tour documents have also been identified and are presented on the Menaka-Archive platform. At the Hamburg People’s Opera (Volksoper), the Reich Broadcasting Company (Reichsrundfunkgesellschaft) recorded one performance on shellac records at the beginning of 1936. These recordings exist until today and belong to the collections of the German Broadcasting Archive (Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv) in Frankfurt am Main. Besides, the Menaka Ballet took part in the German feature film production Der Tiger von Eschnapur in 1937. In this production by Richard Eichberg, the ensemble appears as extras in a scene of the movie. The choreography was an item from the ensemble’s stage repertoire. These are the only moving-image recordings of the Menaka Ballet known to-date. Some other significant individual documents, such as letters exchanged between the impresario Ernst Krauss and the artistic directors of the Stuttgart State Opera (Staatsoper Stuttgart) available at the State Archive Baden-Württemberg (Landesarchiv Baden-Württemberg); a letter addressed personally to Hitler by Leila Roy (Ian Sayer Archive), private collections (The Hanova Sisters’ Collection), or British secret service notes on a member of the ensemble also shed light on a global network (Kuhlmann 2003: 172).

Engaging critically with the Source-Base

Questions of decoding, reading and the historical contextualization of the materials are undoubtedly much more complex than the process of collecting these scattered sources. A critical examination of the source-base is therefore necessary on several levels. First of all, the fragmentary nature of the digital collection presents a special situation. While each new source completes the overall historical picture of the tour of the Indian Ballet in Europe, it also raises further questions. Each new document or object reveals contradictions, gaps, and missing parts, leaving it unclear whether certain documents ever existed or if they were deliberately deleted. (Ernst 2002: 25). A typical cross-section of the finds, for instance, might look like this: A medal from the 1936 international dance competitions, kept in a drawer in Kolkata; a shellac record in the German broadcasting archive in Frankfurt; a photo folder in the theatre archive in Regensburg. Such sources are a few clues amidst which the fates and lives of those involved appear briefly and then disappear again.

In the collections of Menaka Ballet’s impresario Ernst Krauss, for example, the traces of his business partner, the Jewish journalist Nathan Wolf, have been lost. Nathan Wolf’s signature is missing in the minutes of a shareholders‘ meeting in January 1942. This missing signature is the last clue to Wolf’s disappearance. He was murdered in Auschwitz in September 1942. The traces of a member of the Menaka ensemble have also been lost in Germany. Ambique Majumdar, the company’s music director, remained in Germany when the others returned to India in 1938. Majumdar first studied musicology in Königsberg and then worked for Subhas Chandras Bose’s radio station in Berlin. A note in Bose’s biography indicates that Majumdar was killed in the bombing of Dresden in 1945. The years in-between remain a gap in the archive. Finally, Irfan Khan, the grandson of Menaka’s orchestra leader Sakhawat Khan, reports that his grandfather took the precaution of destroying documents from his tour of Germany upon return to India because he feared repression by the British administration. Here, too, it remains unknown as to which items were preserved and which not.

Furthermore, the Menaka Ballet sources require careful contextualization because the Indian ballet moved into several contested cultural and political fields in the early 1930s, where numerous contradictory discourses overlapped.

Menaka’s Ballet was, firstly, an obvious expression of India’s struggle for independence. (And, incidentally, it was perceived as such in Europe.) It was promoted by actors of the national movement as a genuine Indian art form, which strove against the cultural hegemony of the British colonial power – at a time when India’s national independence was still an uncertain project.

Secondly, it was also a symptom of a profound and conflictual socio-cultural change in India itself, which was being negotiated in the arts, and especially in dance, between tradition and modernization (Soneji 2012: 13). This process of modernization in the arts was accompanied by the rise of a new bourgeois class as the promoters of the performative arts, with the simultaneous marginalization of traditional women performers (Walker 2017).

Thirdly, it was precisely these qualities that made Indian Ballet an interesting object for cultural debates in Germany – namely, those along the lines of the National Socialist policy of cultural co-ordination (Gleichschaltung) vs. the modern art of the international avant-garde. The Indian Ballet was thus regarded as modern art, but also as a successful “völkisch”-national expression.

A question that arises is how critics in Europe negotiated the aesthetic criteria for evaluating a previously unknown art form. Here, the spectrum of descriptions in the sources ranges from an erudite ethnographic engagement with the instruments to a cultural appropriation of music and dance into the art-religious concept of a Gesamtkunstwerk, as proposed by Richard Wagner. However, there is no lack of voices that appreciate the performances as an independent, modern form of dance expression. Writing about these reviews and how they belonged to their contemporary contexts requires a careful semantic examination of the sources and a classification of an ongoing change in the culture of bourgeois representation in Europe and Germany.

The Menaka-Archive as Collaborative Research Platform

The Menaka-Archive is an illustration of entanglements that existed between actors from colonized India and those from interwar Germany. Tracing such trajectories hints at histories that cross paths with, but also go beyond the realms of the British empire. The digital Menaka-Archive documents how our search moves through this history and is primarily to be understood as a work-in-progress tool for various interdisciplinary and linked research projects. It serves to visualize historical contexts and to build a documentation and research network. Finally, it is a conceptual framework for an open and collaborative data collection.

The Menaka-Archive has a number of future objectives. The first purpose is to secure and interconnect fragile data. The archival records, some of which are stored under precarious conditions, are to be collected, digitally secured, and rendered accessible to a wider public. One of our main goals is also to identify how the scattered sources belong together. We aim to offer impulses that connect different sources with each other, therein making them „speak“, and to document them as part of a living history of a cultural encounter between Germany and South Asia. Therefore, the Menaka-Archive is not only limited to the purely historical sources of the 1930s, but also includes the results of various research trips conducted in Germany and India, which trace the multi-layered interconnections of the historical encounter and establish new contacts (Schlaffke & Schwaderer, 2019/2020).

As the collection is open, we expect further developments in the near future. Recently, since the website is also listed in international search engine algorithms, descendants, interested researchers, and collectors have been getting in touch to share their private collection items. These are personal letters, photographs, and postcards, but also memories and stories they have preserved in the family. This dynamic is about to turn the Menaka-Archive into a platform for a lively exchange, rendering it a living archive. This implies that our objective is not just to collect only the historical, material sources, but also to connect these to oral histories of various persons related to the tour, which gives the archive a contemporary value. Memories and stories of friends, relatives, or students all over the world come into contact and enable us to weave a dense network of connections that have arisen from the historical event of the Menaka-tour.

A few examples will illustrate this. One of the most important witnesses to the musical significance of the „Indian Orchestra“ is Irfan Muhammad Khan. He preserves today the material legacy of his grandfather Sakhawat Khan, Sarod maestro and leader of the musicians of Menaka’s ensemble, and is a contemporary musician in India himself. For him, this material serves as evidence of his grandfather’s presence as an artist in Germany. Moreover, this material is important for him as it enables him to prove that Muslim artists like Sakhawat Khan have also made a substantial contribution to the intangible cultural heritage of the Indian nation.

As part of the ongoing involvement with the archival sources of the Khan family, Markus Schlaffke produced the documentary film The Albatross Around My Neck, Retracing Echoes of Loss between Lucknow and Berlin (https://vimeo.com/113805297). This film follows the protagonist Irfan Khan over several years as he lives his life as a musician in India and also takes him to a number of performance venues of the Menaka Ballet in Germany, addressing the archive as a contemporary site where practices of transmission are negotiated.

Reflections on the Menaka-Archive materials have been incorporated in a series of publications and events that engage with the objects in the digital collection in various ways. Here we would like to especially mention Parveen Kanhai, museum educator from Rotterdam, who contributed to our project with her profound knowledge of digital archives of the colonial period all over Europe. In numerous smaller and larger articles, she comments on material from the archives and neighbouring sources. Her work shows multiple connections of art to society and politics, and in particular their colonial entanglements, and contextualizes the Menaka performances in the field of cultural policy across the Netherlands and Nazi-Germany in the interwar period.

To open a platform for special findings and discussions, we have created two sections on the website. The main section is the project’s journal (https://menaka-archive.org/journal/), which works like a blog. It provides space for essays such as Isabella Schwaderer’s examination of a question that has haunted the researchers from the very beginning, namely, whether the ensemble really danced for the most prominent political leaders of Europe, as stated by Sakhawat Khan in his memoirs (Schwaderer 2021). Parveen Kanhai contributes regularly to the journal with articles that reconstruct the early body of Menaka’s work, such as her first tour in Europe in 1931, with her dance partner Nilkanta, by using ample material from Dutch newspaper archives (Kanhai 2019). Additionally, this section provides a space for interviews, oral history recordings and other broader discussions.

Conversely, the section Notes on the archive’s website (https://menaka-archive.org/notizen/), presents individual archival sources, mostly photographs, introducing them with the most important information, similar to objects in a virtual museum. This constantly expanding section regularly presents new findings and unexpected curiosities, such as a photograph depicting Menaka and two of her ensemble members on skis (https://menaka-archive.org/en/notizen/india-on-skis/), or the long travels of a printed photograph of Menaka from Berlin to New York (https://menaka-archive.org/en/notizen/photographs-around-the-globe/). These short notes are also published simultaneously on social media channels, namely Facebook, where they gain growing attention by dance practitioners and a wider audience interested in dance history in India and around the world.

Based on a biographical memory of a descendant of a member of Menaka’s ensemble, the digital platform has taken shape step-by-step as an archival body. Today, it serves as an invitation for further discussions and explorations, which we consider to be a process of continuous navigation as well as an artistic and ethnographic exploration of the archive.

Endnotes

[i] All translations done by the authors.

Bibliography

Baxmann, Inge, “Ein Archiv des Körperwissens: Ethnologie, Exotismus und Mentalitätsforschung in den Archives Internationales de la Danse”. In: Inge Baxmann (Hg.) Körperwissen als Kulturgeschichte. Die Archives Internationales de la Danse (1931 – 1952). Unter Mitarbeit von Franz Anton Cramer. Wissenskulturen im Umbruch, Bd. 2. München: Kieser, 2008a, S. 27–48.

Baxmann, Inge, “Rettungsethnologie. Der »fonds folklore« In den Archives Internationales de la Danse und die Erfindung nationaler Tradition”. In: Inge Baxmann (Hg.) Körperwissen als Kulturgeschichte. Die Archives Internationales de la Danse (1931 – 1952). Unter Mitarbeit von Franz Anton Cramer. Wissenskulturen im Umbruch, Bd. 2. München: Kieser, 2008b, S. 89–116.

Bublitz, Hannelore, Das Archiv des Körpers: Konstruktionsapparate, Materialitäten und Phantasmen. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2018.

Ernst, Wolfgang, Das Rumoren der Archive: Ordnung aus Unordnung. Berlin: Merve-Verlag, 2002.

Joshi, Damayanti, Madame Menaka. New Delhi: Sangeet Natak Akademi, 1989.

Kanhai, Parveen, Love, Separation and Unity. Contextualizing Menaka’s Dance-Drama “Krishna Leela”, Journal (Menaka Archive), 2019, https://menaka-archive.org/en/forschung/love-separation-and-unity/. (Last accessed: 20. 10. 2021).

Kanhai, Parveen, Shared Spirits of Poetry and Nation, Notizen (Menaka-Archive), 2020, https://menaka-archive.org/notizen/shared-spirits-of-poetry-and-nation/. (Last accessed: 20. 10. 2021).

Kuhlmann, Jan, Subhas Chandra Bose und die Indienpolitik der Achsenmächte. Berlin: Verlag Hans Schiler, 2003.

Schlaffke, Markus, director, The Albatros around my Neck – Retracing Echoes of Loss between Lucknow and Berlin, Norient, 2016, 01:03:00. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thealbatrossaroundmynff/. (Last accessed: 20. 10. 2021).

Schlaffke, Markus, “Die Rekonstruktion des Menaka-Archivs: Navigationen durch die Tanz-Moderne zwischen Kolkata, Mumbai und Berlin 1936–38”. Unpubl. PhD diss., Weimar, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar. 2021.

Schlaffke, Markus, Isabella Schwaderer, (Re-)connecting embodied archives. Künstlerische Forschung im Zinda Naach-Kollektiv, wissenderkuenste.de, no. 8, November 2019 / Dezember 2020, https://wissenderkuenste.de/texte/ausgabe8/re-connecting-embodied-archives-kuenstlerische-forschung-im-zinda-naach-kollektiv/. (Last accessed: 20. 10. 2021).

Schwaderer, Isabella, Did Menaka Dance for the „Führer“? New Material from the Sayer Archive, Journal (Menaka-Archive), 2021, https://menaka-archive.org/en/forschung/did-menaka-dance-for-the-fuehrer/. (Last accessed: 20. 10. 2021).

Soneji, Devesh, Unfinished gestures. Devadāsīs, memory, and modernity in South India. Chicago, IL, London: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

Walker, Margaret E., India’s Kathak Dance in Historical Perspective. London, New York: Routledge, 2017.

Markus Schlaffke, Fakultät Kunst und Design, Bauhaus-Universität Weimar

Isabella Schwaderer, Theologische Fakultät, Christian-Albrechts-Universität Kiel

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029