By Vandana Joshi

Published in 2020

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00025

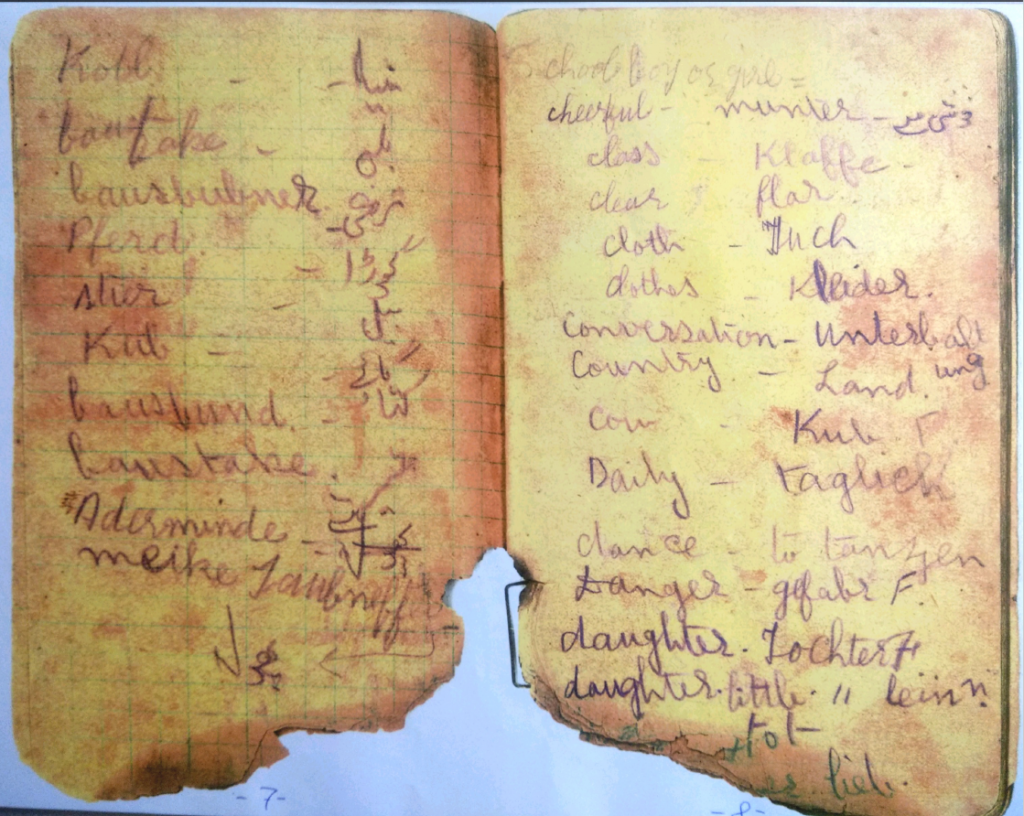

Fig. 1: A page from Sohan Singh’s prison diary containing translation of German words into Urdu and English. Courtesy: Volker Kummer’s Private Collection

Table of Contents

The Problem of Methodological Nationalism | European Archives: Provenance and Pertinence | The Prison Notebook as a Historical Source | The Legacy | Cosmopolitan Soldiering | Colditz Oflag IV C | Dr. Birendra Nath Mazumdar’s Sound Recording | Endnotes | Bibliography

This piece is dedicated to the memory of prisoner Sohan Singh and his transnational nurturer, the ‘hobby historian’ Volker Kummer, a member of the Annaburg Association for the Preservation of local history and Heritage (Annaburger Verein für Heimatgeschichte und Denkmalpflege) who relentlessly searched for eyewitnesses of WWII in India. I am indebted to Professor Rahul Peter Das, the custodian of Volker Kummer’s private collection, who entrusted me with it. While handing over his collection, Kummer urged Professor Das to give it to a ‘real’ historian. I am humbled to be its recipient and hope that I have been able to do justice to it. Kummer’s institutional collection is housed in Annaburger Amtsmuseum.

The above image is taken from the prison notebook of a British-Indian Prisoner of War, jangi qaidi, in contemporary German parlance[1], Sohan Singh. He spent three years in the castle prison of Annaburg located in Saxony. During his captivity he filled 64 pages of his prison notebook. Annaburg had the largest concentration of jangi qaidis and was the recruiting ground for Subhas Chandra Bose’s INA or the Indian Legion during WWII. According to British sources, out of 12,000 British-Indian prisoners, who landed in German camps, not more than 3200 trained ultimately as the 950th Regiment under the SS.[2] The International Red Cross visitation report’s highest tally of Annaburg inmates recorded on 15.5.1943 puts the total strength at 4323 of whom 2736 were out with labour detachments.[3]

While the Legionaries have been a subject of several books in India and abroad, ordinary jangi qaidis who did not defect have attracted little academic attention. This neglect can be attributed to both methodological approaches and linguistic barriers of the multi-lingual European archives.

The Problem of Methodological Nationalism

Soldiering in organized twentieth century warfare spilled over the boundaries of nation-states, yet narratives of war have been penned within the framework of methodological nationalism. The irony of the nationalist paradigm becomes glaring in view of the fact that the number of British-Indian soldiers reached the mark of 2.4 million and became the largest army ever raised by any warring force. Britain fought the war as an empire, yet when it comes to mythologizing the war, the tight skin of British nationalism squeezed in the experiences of a diverse British-Indian army, rendering the colonial soldiers invisible in history, memory and memorialisation. Britain was quick to mythologise the war as “people’s war” celebrating “the Blitz spirit of wartime British cities”, “the Colditz myth” and the British soldier’s stoic masculinity. However, colonised soldiers trained and fought with the same spirit, ethos and culture were largely kept out of the politics of representation and mythmaking. Soldiering in captivity added yet another layer to the whitening of historiography. Despite the successful escape attempts of a few Indian officers, Kochavi (2005) mentions British-Indian soldiers in three pages in total as mere statistics and Mackenzie (2005), while busting the Colditz myth, does not even register the presence of British-Indian soldiers.

A second problem facing researchers who wish to explore these hitherto ignored lives is that of accessibility to multi-lingual European archives, specifically for the Anglo-American world’s historians of South Asia. Though they have recently started addressing the invisibility of British-Indian soldiers by focussing on the impact of WWII on the home front, narratives from German captivity still elude them as they have not been able to fully use the diverse multi-lingual European archives.

A third problem is that the South East Asian Theatre of War (combats in Burma, Malaya, Singapore, and India) has attracted relatively more attention due to the much larger number of INA soldiers raised in Japan and their actual combats against the British on the eastern frontiers of India.[4] The German narrative, with a few exceptions such as Günther (2003), too has been largely preoccupied with the INA and Boses’s activities rather than the everyday life of ordinary captives.

European Archives: Provenance and Pertinence

Underneath the rich national and international provenance based European holdings in the Foreign Office Archives, Berlin, International Red Cross Archives, Geneva, ITS, Bad-Arolsen, Military Archives, Freiburg,[5] to name a few, there is a layer of unutilized material based on the pertinence-principal, such as private collections of Indophile historians and activists, that has the potential of adding new perspectives and depth to the experiences of war. This post combines these two types of sources, with a focus on the latter as a case study, to reconstruct a universe of captivity in Saxony, which saw the largest concentration of British-Indian POWs.

Sohan Singh’s prison notebook is a rare piece of historical evidence preserved by Kummer. It is unique, illustrative, instructive, and emblematic as I shall show in the following pages. Singh was one among the innumerable Sikh soldiers who served the imperial army from its inception. The Sikhs were categorised as a martial race by the British and nurtured with benevolence to serve the military needs of Empire thereby hoping to ensure their loyalty. Singh was also a typical young soldier who joined the army in the wake of an aggressive recruitment campaign, in which the physical qualifications were lowered and the age bracket expanded to mobilise larger numbers. Most of the new ordinary recruits were ‘peasants in uniforms’ with few options of earning a living in villages. A career in the army entailed a promise of incentives, offers, recognition, earning while learning, besides the traditional benefits of pay, welfare, and land grants.[6]

When Singh was taken prisoner, he was barely 18. With little formal education and training, young recruits were sent to face the fury of Rommel’s highly professional and well-equipped German army divisions. Most of them were captured in North Africa without offering much resistance and were brought to German prisons via Italian camps.

The Prison Notebook as a Historical Source

Singh’s prison notebook has the size of a pocketbook. It does not have a cover, the handwriting is faded and smudged in places, and the edges of the yellow brittle pages have frayed at the bottom. It has no page numbers and dates to give us a sense of time. Nonetheless, it is a rare ego document that gives us a peek into the mind of a regular jangi qaidi and thus a valuable piece of textual evidence from the kind of prisoners who found it challenging to navigate through their everyday life in a culturally and linguistically strange cosmos and taught themselves how to deal with it.

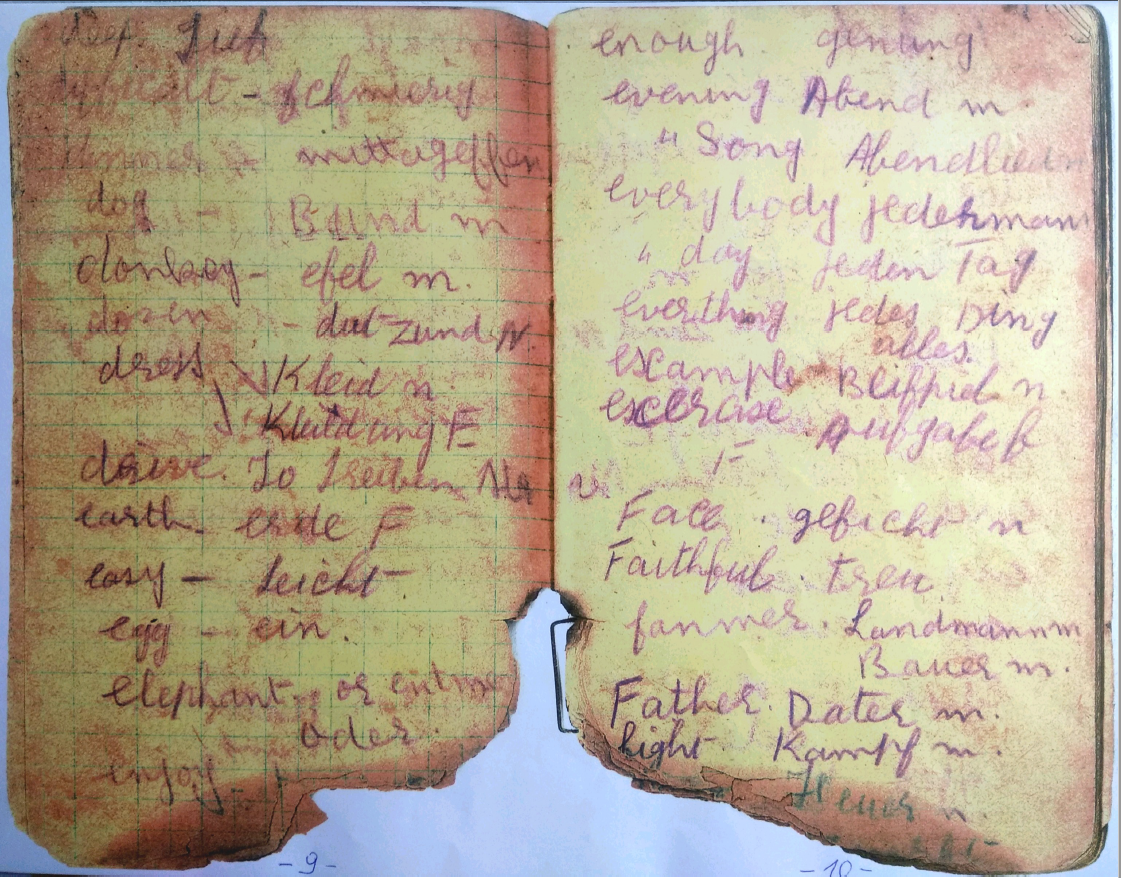

The notebook is perhaps the only surviving piece of writing by a jangi qaidi. It offers clues to his hopes, aspirations, dreams, and desires although it is coded at times. The first few pages show his efforts to learn words in German by noting their meaning in Urdu, the script he was most familiar with. He noted down German terms for body parts, animals, clothing, relations and so on which he wrote next to their Urdu equivalents, as the cover page image shows. In the next few pages, one could see a transition from Urdu to English as he scribbled more words of everyday use in German and English.

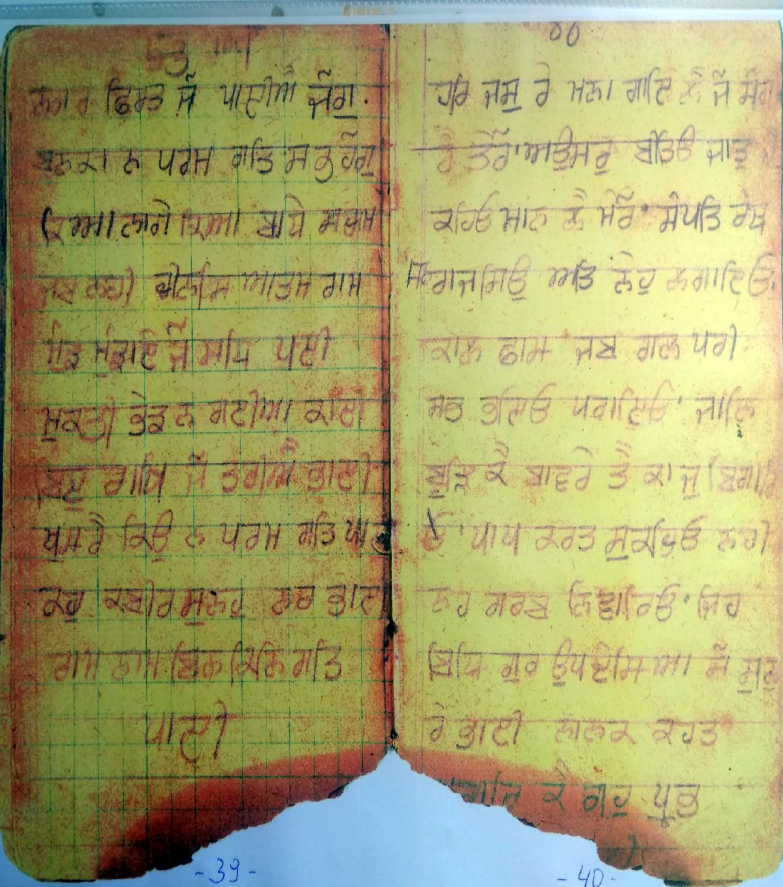

His notebook entries from then on show a pattern of learning from a bi-lingual English German dictionary. Several pages thereafter contain beautifully written Sabads from Gurbani (Guru Nanak’s preaching in the holy book of Sikhs, Guru Granth Saheb) in the Gurmukhi script. This method of learning was quite typical for self-taught people in India until the very recent advent of the computer, where learning by watching YouTube tutorials or vocabulary trainer applications has become commonplace.

Children as also adults from vernacular schools crammed up words from the dictionary in the hope that one day they would be able to master the language of the elite. In wartime Germany too, European prisoners often carried a bi-lingual pocket dictionary to facilitate conversations, especially with local women. It became an important tool, besides previously learnt skills of plumbing, gardening and carpentry that almost worked as a social lubricant in cultivating friendships by fixing locks, doors, bathtubs, and the like for their German acquaintances. German spoken without syntax and grammar became the lingua franca of the camp universe. Singh’s notebook is a representative example of an alien’s desire to socialize and blend in.

A few pages after these language lessons, he wrote down some dates with names of fellow prisoners, dead, liberated or those he was looking for. Sadly, the details of his mental processing are lost to us as we cannot decipher why he wrote down some other dates and addresses. But one we know for sure: 24.4.1945, next to which he wrote, Chutti ka din in Urdu: the day of liberation.

Three German names figure in it too. One that he tried to write himself reads Mahagret. Right below that two names were written in German style: Margarete Kurthäuser and Heinz Kurthäuser. These, I suppose were written by some friendly German who tried to teach him how to write their names correctly, most probably Margarete herself. Another name found in his notebook was Hildegard Kossagk.

The Legacy

Singh’s story did not end after liberation. On 15.02.1974, he wrote a letter from Bazpur to Kurt Kossagk, Hildrgard’s husband.[7] By then he had taken the title of Subedar. He reminded Kossagk that he had worked on his farm. He told Kurt that he was the owner of a big farm, had bought a Romanian tractor, and worked on the farm with his sons. This half page letter was written in German. Barring a few grammatical errors, the letter was able to communicate its purpose. He wished to travel to Germany to visit them at his own cost and requested for help with visa and other formalities. However, his wish did not materialise due to travel restrictions during the Cold War.

After the collapse of the Berlin Wall, his story took another turn. Volker Kummer, the hobby historian of Annaburg, traced him and Singh became a regular item on Kummer’s travel itinerary along with Netaji’s Research Centre in Calcutta. Singh hosted him with great warmth and hospitality on each visit. The local newspapers in Saxony carried special columns on Kummer’s visits and reported about the great conversations they had despite his school English and Singh’s limited abilities to understand him. It was reported that in 2008, the 84 years old Singh once again expressed the wish to visit Annaburg with a companion. Kummer hoped to raise funds from Annaburg’s Association, German-Indian Society (Deutsch-Indische Gesellschaft), and others. However, his efforts and Singh’s wish did not bear fruit. Long after his return to his roots, his family, and traditional profession in which he made great advances, Singh’s spirit sored high on a transcultural horizon despite his inability to cross national borders.

Cosmopolitan Soldiering

Through this illustrative story I would like to dwell on the concept of cosmopolitan soldiering of the jangi qaidi in WWII. Although a few prisoners made successful escape attempts, most realized it was a tough and futile exercise and tried to go on with their lives with as much accommodation and flexibility as allowed them to navigate through the camp life, monotonous at best and cruel at worst, along with finding venues for creativity and enterprise where possible.

The large majority saw captivity as an opportunity for transnational, cross-cultural interaction to mitigate their distress, amuse themselves or fulfil their wishes. In Annaburg there were POWs of other nationalities too with whom jangi qaidis bartered, played, socialised, and indulged in forbidden activities. Bose himself visited the camp thrice for his recruitment drive. This brought along an opportunity to exercise individual agency. The camp became a centre of rumours, spies, and mutual rivalries for resources. Men were lured with better food, attractive uniforms, and local girls to join the INA and when this did not work senior legionaries gave lashings to the non-compliant ones. Withdrawal of the Red Cross parcels and post from home were other methods of reprisals. Even then, the majority stayed as ordinary captives.

These loyal ‘peasants in uniform’ underwent a transformation of their own kind under the influence of their mates, international prisoners and employers, if they happened to be kind, as was the case with Singh. Despite language barriers they assumed, consciously or unconsciously, habits and ways of doing things as they were done by others around them. This created a cosmopolitan environment of learning by doing. Singh’s example shows that jangi qaidis learnt the lingua franca of the camp universe. Singh may not have been alone in spending some quiet time in the library learning German with the help of a bi-lingual dictionary. He came out of captivity a self-taught polyglot, however limited in his command of German. His spirit to learn taught him to navigate in his everyday life in multiple languages, so much so that he even wrote a letter to Kurt Kossagk in German in 1974.

The larger point that I am making through this micro case study is the cross-cultural, transnational cosmopolitanism that brought to bear its influence on the jangi qaidis. Looking at the experiences of soldiering in captivity through the lens of the soldier, which Singh’s notebook helps us in doing, we can discern that the concerns of ordinary soldiers were at variance with those of the political elite whether British, German, or Indian nationalist.

Colditz Oflag IV C

Let us zoom out of the prison notebook and zoom into another Castle prison, Colditz, also located in Saxony. This Renaissance style hunting lodge was turned into Oflag IV C which housed “incorrigible” officers from all possible nationalities who had attempted escapes on earlier occasions. Reverend Courtenay, a British inmate of Colditz, called it a punishment camp where all prisoners with nuisance value were thrown in and were regularly beaten for bad behaviour. This did not dampen their spirit and they continued with their pranks, escape attempts, adventures, and amusing activities. The Reverend remembered having laughed the most in his life in Colditz because of the people there. He described the nuisance makers as tremendously skilled, determined, aggressive, and spirited, who, among other enterprising activities, even formed an escape committee to help whoever wanted to escape and developed a great sense of solidarity.[8] Courtenay’s witty and light-hearted rendition of life in Colditz offers quite a contrast to my second case study, an Indian medic, also an inmate of Colditz, Dr. Birendra Nath Mazumdar.

Dr. Birendra Nath Mazumdar’s Sound Recording

Dr. Mazumdar from the Royal Armed Military Corps was captured in Etaples, France, and taken through sixteen or seventeen Stalags before finally landing in Colditz. At Colditz, Mazumdar suffered unusual mental agony and physical torture due to his colonial Otherness, for being labelled a spy and a Gandhi chap by British inmates, and also because of his stubbornness and refusal to join the INA. The highpoint of pressure came when he was escorted to Berlin to meet Bose in person. After making him comfortable by conversing in Bengali, Bose said in English, “You know why you are here? We are forming the Indian Legion. I want you to join us.” Mazumdar said, “I cannot, and I would not”. “Why? I have done it”, said Bose to which Mazumdar replied, “You had the opportunity to resign and escape. I was taught, a promise once made, you have got to abide by”. Bose left him with the words, “I do not think we should meet again”.[9] After his return from Berlin, he went on a five-week hunger strike demanding his freedom and eventually escaped. He reached Geneva with the help of a French resistance fighter, contacted the Swiss Immigration Office, got the permission to stay and pursue further studies. Soon he started dating a Swiss girl. He was then forced to disrupt his studies and go to Locarno with other Indian soldiers.

These are snippets from a two-and-a-half-hour oral interview, recorded in 1996, of the then eighty-year-old RAMC medic in the sound archives of the Imperial War Museum. This was the first time ever that a British-Indian officer spoke to his erstwhile masters about his trials and tribulations during his German captivity. The twists and turns of his colourful and adventurous story give us insights into the perils and prospects of Indian captives, not just in German Stalags (prison camps for ordinary soldiers) and Oflags (camps for officers), but also at the hands of their own British fellow inmates and the Raj in the form of subtle racism, veiled threats, looming suspicion, political taunts, professional rivalry, and sheer neglect in the post-war era. Many a British-Indian captive may find an echo of their own voice in Mazumdar’s rendition.

Like the prison notebook of Sohan Singh, this rare primary source from the sound archives of the Imperial War Museum opens another window to the microcosm of captivity for those ‘promise keepers’ who resisted all lures and pressures to join the Indian Legion during captivity and were moved in and out of the grey zone of collaboration until after their repatriation. Having said that, Mazumdar was an officer, who despite facing isolation, hostility, and constant accusations of espionage from his British counterparts on the one hand, and torture or temptations from his German captors on the other, enjoyed access and opportunities to things seldom available to an ordinary prisoner in German captivity, such as socialising with White women, continuing his studies in Switzerland after a successful escape, and eventually, returning to the UK, where he lived with his wife until his death.

As a source, the eyewitness account of Singh’s prison notebook gives us a visual experience with several gaps, coded notations, interrupted textual flows, and lack of coherence, whereas Dr. Mazumdar’s detached and monotonous aural rendition is characterized by the accuracy of details, fluency of speech, political awareness, and unwavering determination. These differences owe to their different class origins and training that offered them different sets of tools and opportunities of social mobility. In several other ways, however, the experiences of these ‘promise keepers’ intersect. Despite the lures and threats by the legionaries and the guards, both stuck to their guns. Both sought transnational contact, maintained professional ethos, and showed comradery in the face of adversity. Mazumdar got his clue to why he was being ostracised by British inmates. The French and Dutch inmates told him that they called him a spy. Until then he thought he was just being teased as the ‘bloody Gandhi chap’. Mazumdar then overheard the word spy in the washroom. He went up to Major Henry and asked, “Did I hear you say I am a spy?” Then he gave him five minutes to withdraw his statement after which he hit him on his head. The six feet tall British officer fell flat on the floor. The Germans on their part also continued to exercise pressure tactics such as not shifting him to an Indian camp which might have ended his sense of isolation and feeling of victimization[10] at the hands of his own British colleagues. He finally made a successful escape attempt from a moving train and reached Geneva. While in Geneva, he confronted another British officer when the latter told him not to socialise with a Swiss girl and only with his countrymen. Majumdar retorted, “You cannot chain me. I am a free man”.[11]

Mazumdar finally settled in the UK with his wife after the war while Singh became a successful farm owner. What they both practiced long thereafter was derived from lessons they had learnt in captivity: resilience, adventure, and reciprocity across lines of nations, colour, and faith. This piece is a small tribute to the ‘cosmopolitan spirit’ of the jangi qaidi.

Endnotes

[1] This is how Indian POWs were addressed in camp notice boards and official instructions. The camp language was Hindustani written in Roman script.

[2] TNA WO 208/802

[3] ACICR, C SC, Stalag IV D/Z 15.05.1943

[4] For recent literature on the visibalisation of British Indian soldiers in WWII, the impact of the war on the home front and military-society relationship in South Asia see: Barkawi 2017, Bayly 2005, Douds 2004, Raghavan 2016, Khan 2015 and Khan et. al. (ed.) 2017.

[5] Das politische Archiv Auswertiges Amt (PAAA), International Tracing Service (Internationaler Suchedienst) archives in Bad Arolsen (ITS), Federal and Military Archives in Freiburg (Bundesarchiv – Abteilung Militärarchiv/BA/MA Freiburg).

[6] For recruitment strategy and campaigns during WWII, see Khan 2015, pp.40–49, Raghavan 2016, pp. 64–78, Bayly, 2005 281–5

[7] Bazpur is located in the Himalayan foothills of Kumaon, Uttarakhand. It is an affluent city whose inhabitants are mainly Punjabi migrants from the postwar, post-Partition era. These industrious and enterprising migrants turned the Tarai (wetland) into an arable agricultural land and became large estate owners. Bazpur is close to Nainital, a famous colonial hill station, and Rudrapur, an industrial town.

[8] Imperial War Museum (IWM), Sound Archive, 10771

[9] Imperial War Museum (IWM), Sound Archive, 16800

[10] PAAA R 40985. On 21.5.42 the German Military High Command (OKW) wrote to the Foreign Office in response to the Swiss delegation’s recommendation that it was out of the question to transfer Mazumdar to an Indian camp due to special reasons. The communication also stated that doctors and spiritual leaders could be granted special privileges such as special rooms, double letters, post cards, weekly 2.5 hours walks outside the compound if their behavior was unobjectionable. The denial of such privileges was a routine punishment given to troublemakers, besides beatings.

[11] Imperial War Museum (IWM), Sound Archive, 16800

Bibliography

Barkawi, T., Soldiers of Empire: Indian and British Armies in World War II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Bayly, C. A., Tim Harper, The Forgotten Armies: Britain’s Asian Empire and the War with Japan. London: Penguin, 2005.

Douds, G. J., “The men who never were: Indian POWs in the Second World War”. South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 27, 2 (2004): pp. 183–216.

Khan, Yasmin, The Raj at War: A People’s History of Indian’s Second World War. London: the Bodley Head, 2015.

Khan, Yasmin, Gajendra Singh, and Ashley Jackson (eds.), An Imperial World at War: Aspects of the British Empire’s Experiences at war 1939–45. London: Routledge, 2017.

Kochavi, Arieh J., Confronting Captivity: Britain and the United States and Their POWs in Nazi Germany. North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

Günther, Lothar, Von Indien nach Annaburg. Berlin: Verlag am Park, 2003.

Mackenzie, S. P., The Colditz Myth: British and Commonwealth Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Raghavan, Srinath, India’s War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia. New York: Basic Books, 2016.

Vandana Joshi, Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029