By Anandita Bajpai

Published in 2018

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00005

Image: Joachim Heidrich Nachlass, Zentrum-Moderner Orient, photograph by author, December 2017

Table of Contents

Trajectories of the collectors – Joachim Heidrich and Petra Heidrich | Emergence of collections and the life worlds of an archive | “Whose collection?”: From materially entangled sources to a virtually entangled database | Sustaining Inner Architectures, Articulating new Structures | Endnotes | Bibliography

The Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) was established in 1996. Its predecessor institution, the Forschungsschwerpunkt Moderner Orient, emerged in 1992 from the Institute for Universal History (Institut für Allgemeine Geschichte) of the Academy of Sciences (Akademie der Wissenschaften) of the German Democratic Republic (GDR). The ZMO library and archive consist of significant collections of private papers besides hosting multifarious and extensive literature on historical, anthropological and political themes engaging with the Middle East, Asia and Africa as its regional focus. The private papers’ holding of the archive comprises collections by three eminent East German scholars – Horst Krüger (1920–1989), Joachim Heidrich (1930–2004) and Petra Heidrich (1940–2006) – who researched on South Asia related themes. In the case of these three scholars specifically, the archival holding consists of research related papers and no personal diaries or other ego documents of the individuals. Temporally, their collections commenced in the 1960s and continued through the Cold War years (the themes researched have files that date back to colonial India of the early twentieth century).

In a seminar organised within the framework of the BA and MA courses offered at the Department for South Asian Studies, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (one of the three partner institutions of the MIDA project), the team and the attending students studied, catalogued, indexed and digitized the papers of Joachim Heidrich and a part of those of Petra Heidrich. This entry will outline the theoretical and methodological considerations which inform the process of cataloguing a private collection. It is organised along three primary axes and utilizes the collections as an illustrative case study for revisiting larger questions on archival architectures. The main objective of the post is thus to transparently share the process of cataloguing a collection into a database with readers and initiate a discussion on questions related to the entangled nature of archival collections and how researchers de-and re-constitute their architecture.

Trajectories of the collectors – Joachim Heidrich and Petra Heidrich

Joachim Heidrich (13.07.1930–08.07.2004)

Joachim Heidrich, born in 1930, studied ethnology (Volkskunde) and successfully finished his doctoral dissertation in 1958. His original training was in Indology coupled with a profound knowledge of the history and languages of India. Between 1973–81, Heidrich lived in India and held several portfolios for the GDR’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, including different positions at the embassy in New Delhi and that of the Consulate General of the GDR in Calcutta. From 1981–1989, he worked at the Central Institute of History (Zentralinstitut für Geschichte) followed by the Institute for Universal History (Institut für Allgemeine Geschichte) at the Academy of Sciences (Akademie der Wissenschaften) of the GDR. After this, and until 1995, he worked at ZMO’s predecessor institution, the Forschungsschwerpunkt Moderner Orient.

Petra Heidrich (13.11.1940–31.1. 2006)

Petra Heidrich was born in 1940 in Berlin. She studied Indology and Social Anthropology at Humboldt- Universität zu Berlin. In 1965 she joined the Institute of Oriental Studies, at the Academy of Sciences of the GDR. Her research primarily focussed on social aspects of the agrarian question in India as well as on the Indian peasant movement and its leaders in preand post-independence India. During the 1970s, she spent several years with her family (Joachim Heidrich, mentioned above was married to Petra Heidrich). In 1983 she obtained her Ph.D. from the Academy of Sciences of the GDR and was a staff member of the Institute of History till the dissolution of the Academy of Sciences after the unification of the two Germanys. In 1992 she joined the Zentrum Moderner Orient in Berlin and continued her research on social problems of modern and contemporary India. Her publications (mainly in German and English) include contributions on rural development programmes, on the peasantry and peasant leaders, on the role of agricultural labour and on social and religious reform movements in colonial and independent India. In the last years of her employment at the centre, she worked on a comparative biography of the two peasant leaders– Swami Sahajanand Saraswati and N.G.Ranga

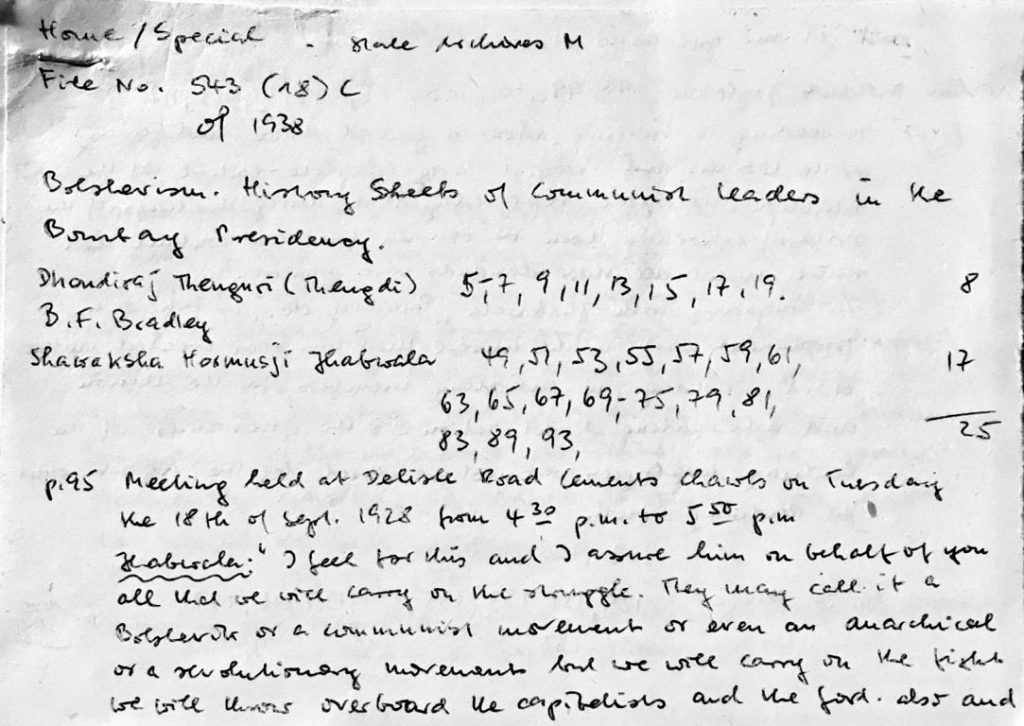

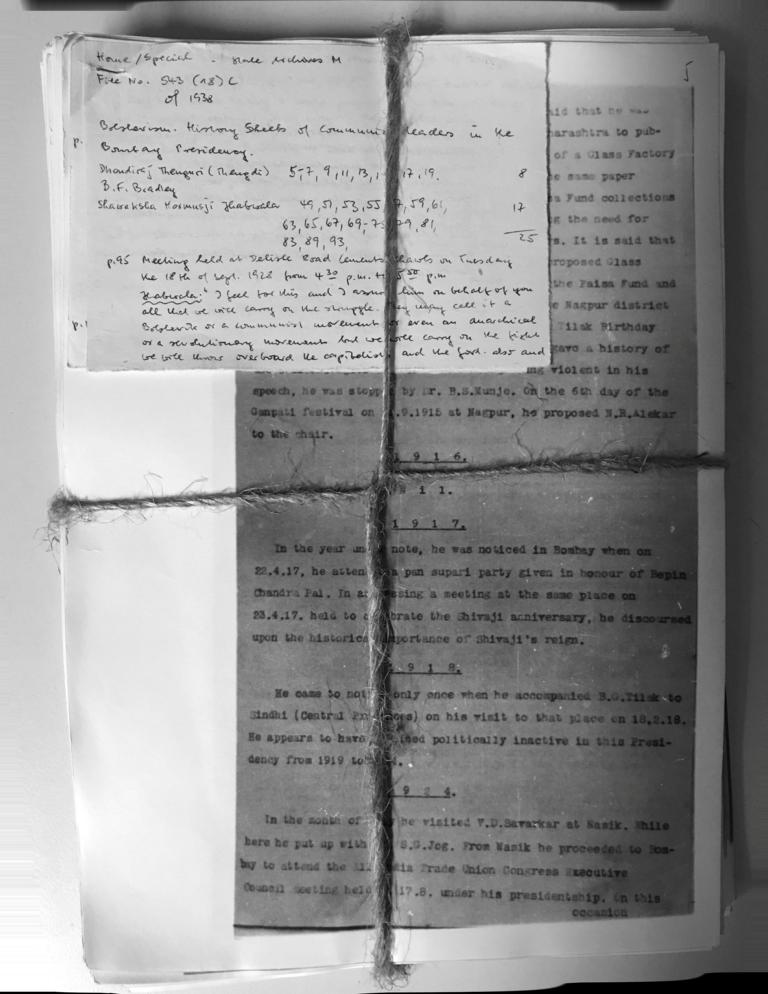

The Heidrich collections at the archive of Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient comprise copies of Indian newspaper articles, rare literature and files from diverse Indian archives and libraries in Patna, Delhi, Kolkata and Mumbai. Among others, the boxes consist of copies of pamphlets, magazines, minutes and proceedings of meetings, letters, reports, microfilms and their printed out hard copies as well as hand-written notes (see figures 2a and 2b) and indexes. These different kinds of sources cover numerous themes that are relevant for social historians of India– the labour and peasant movements in India, agricultural problems in postcolonial India, the development of the All India Kisan Sabha (All India Peasants’ Union), the emergence of different political currents during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, communism and sources related to the history of trade unionism in India.

When studied closely the collected files show that their individual research interests also intersected on numerous themes. The collections become a window to their academic world and the specific themes that evoked their intrigue.

Emergence of collections and the life worlds of an archive

Any attempts at cataloguing and understanding the internal organizing architecture of a collection or an archive necessitates gaining background knowledge of the history of the collection or the holding. The intentions and the criteria that led to the collection of sources (documents/texts/objects) help gain a comprehensive overview of the historical motivations that triggered the collection and its eventual incorporation in a particular archive. In the case of the Joachim and Petra Heidrich private papers’ collections (Nachlass), these motivations are somewhat obvious. As two GDR scholars who were historically and anthropologically interested in British and post-colonial India, their collection opens a vibrant spectrum of topics that they deemed crucial for research on India within the overarching framework of academia in the GDR. Their personal trajectory also adds an interesting layer to the collections. As residents in India for over eight years, a rarity for most historians as well as anthropologists, both indeed profiteered from extensive archival visits, often also collecting an exhaustive range of sources on themes, which did not necessarily find their way into their publications directly. Thus the collections, when contrasted with the lists of publications of the two scholars, also show which sources were effectively used to materialize publications as well as sources on those topics that continued to evoke interest for a sustained period of time but could not take the shape of published work.

As mentioned, the themes one encounters in the sources are diverse and multi-layered. Among others, they relate to – The All India Trade Union Congress, the role of religious leaders in the peasant movement in the 1920s up to independence, agrarian and peasant history, peasant revolts, trade unionism and strikes, the caste question, proceedings of the Communist Party of India and its role in the independence movement as observed in secret reports of the Home Department of the colonial government and a comprehensive overview of the history of the political Left in India. These consciously elected themes not only reveal the kind of academic interests in India that were triggered by the two scholars within the GDR, but they also reflect the overarching framework of socialism and communism inspired academic traditions of the GDR more generally.

Joachim Heidrich’s collections also become interesting from another perspective. As an anthropologist who pursued a career in diplomacy and acquired positions within the embassies soon after the GDR was recognized by the Indian government, his life trajectory offers telling details about the ranks and files of GDR diplomacy in India more generally.

These were not diplomats who did rapid crash-courses on the subcontinent before embarking onto their diplomatic careers, but very often, carefully selected individuals who had had a sustained, long-term academic interest in South Asian history and politics. Joachim Heiderich, eventually re-turned to academic research after being in diplomatic positions between 1973–81. Thus, his collection, when viewed from the historical lens, reveals certain important elements– (1) The intersection of diplomatic and academic careers; (2) A long period of residence in India which enabled the Heidrichs to extensively consult and copy an exhaustive list of primary and secondary sources on Indian history from very diverse archives across the county and (3) The reflexive awareness that the collection could be highly relevant for the future generation of scholars engaging with South Asia, as is also revealed by their careful indexing, ordering and listing of sources.

“Whose collection?”: From materially entangled sources to a virtually entangled database

The Heidrich collections are unique in that they consist of sources from Indian archives and libraries solely and, unlike most holdings from German archives that have been catalogued and indexed in the MIDA database, they do not have a single file in the German language. They are a special illustration of entangled archives whereby it is not just the contents of files but also rather the physical presence of sources on India from India in a German archive that interlinks holdings in India to those in Germany. Besides, the collections also indicate the entangled life trajectories of the two GDR scholars of India who were also a couple in private life. This has also borne consequences for how the sources have been listed in a format that is based on the structure of the database. For example, Box 2.4 from Joachim Heidrich’s collections consists of sources on Swami Sahajanand Saraswati, an ascetic and a peasant leader, who also founded the All India Kisan Sabha in 1929. A brief overview of Petra Heidrich’s scholarly interests and publications may suggest that these were sources collected by her for her comparative research on N.G. Ranga and Sahajanand Saraswati. As researchers cataloguing the collection, we are unaware if the contents of Box 2.4. came to be inserted in the Joachim Heidrich collection as an act of collecting by the two researchers themselves of by the two persons who assembled the material and were responsible for enabling their transfer to the archive after Petra Heidrich’s death. This realm of uncertainty and ambiguity is almost certainly part of the process of cataloguing for all archives. In this case, officially, the Box continues to be part of the Joachim collection at the archive and precedence was given to the ordering in which the sources were inherited. Thus, in order to ensure that the files appear as part of the Joachim Heidrich collection to not disturb the provenance of the ZMO archive and, at the same time, indicate that they clearly were in fact collected by Petra Heidrich, such files have been listed under the Petra Heidrich Nachlass catalogue in the final list based on the structure of the MIDA database. However, those listing the sources for the database have ensured that readers, when reading the description of the box’s contents are duly aware that it actually is physically placed in Box 2.4 of the Joachim Heidrich collection. The team listing and indexing these sources was often confronted with the question of whether in such obvious cases the files should be separated and placed in the respective collection’s boxes or if it would be beneficial to put both the collections together as one collective holding in the name of both the researchers. We thus see how the act of ‘virtual’ or ‘digitial’ re-ordering, whereas actually bearing no consequences for the physical place of the sources (all boxes, whether from Petra or Joachim Heidrich’s collection, are placed on neighbouring shelves in the same cellar) does bear consequences for how sources will be seen, accessed and re-placed/contextualised in future individual research. All of this can thus result from a minute act of the cataloguing researcher.

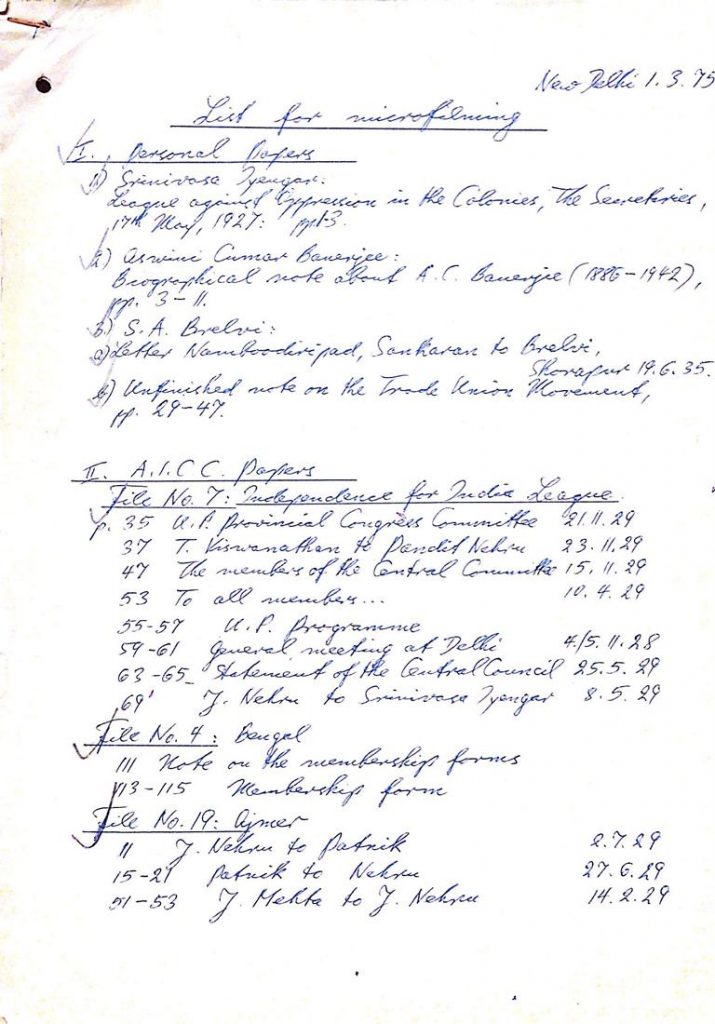

On a similar tone, in one of the other boxes, one encounters a hand-written list of archival entries for microfilming, which has been signed by Horst Krüger (perhaps part of the regular exchange which Krüger had with the two Heidrichs?). The list was inherited from the Heidrich house and thus continues to be a part of the Heidrich collections (see figures 4) and not the Krüger papers though once again, the description of the contents of the box mentions that the list was actually prepared by Horst Krüger. Such seemingly minute and banal issues often become complex topics for archivists more generally when organizing “the place” of holdings in larger archives.

One of the objectives of the MIDA Archival Guide is to reflect on how the turn towards entangled transnational and global histories not only raises new theoretical questions but also confronts us with methodological issues on the relationship between entangled histories and archives.[1] Discussions on archives and their intertwined architectures need to be incorporated in our engagements with entangled histories. The Heidrich collections housed by the ZMO archive are an illustrious example of how entangled archives reflect, and often are a trace of, pasts, which are more interwoven than territorially, containing state archives would lead us to believe. They become a window not only to the academic visions of the two scholars but also show the legacy of India-related research interests in archives which are not colonial, and belong to a new institutional structure since the reunification of the two Germanys. The collections also point to the importance of smaller archives, which can enable scholars to shift their focus away from the territorializing logics of larger state archives. Thus, we see that the Heidrich collections give us an idea of the topics that interested the two scholars, especially within the overarching context of social sciences in socialist GDR. The collections can be highly beneficial for scholars interested in the history of the Communist Party of India, peasant movements and trade unionism. In more ways than one they are an archive within an archive given that the sources were copied from Indian archives, are often to also be found in colonial archives and are housed in a German archive.

Unlike the holdings of most German archives, which chronicle the history of Indo-German entanglements more directly by mirroring sources that enable writing bilateral histories, these collections can tell volumes about entangled life trajectories of GDR scholars who were interested in studying colonial and postcolonial India. This can be a fruitful area of research in its own right that has hitherto been relatively unexplored, especially in the midst of the politics post 1989 and the making of ‘national’ meta-narratives. The transitions of 1989 provoked drastic shifts in the organisation of the GDR’s universities and often resulted in sudden halts in the careers of numerous academics.[2]

This larger transformation also impacted the academic careers of several scholars of South Asia in the GDR. Although Petra Heidrich could continue with her research at the ZMO after the transitions faced by theGDR’s Academy of Social Sciences, it was the rejection of her last funding application in 2000 that brought her official academic career to an unexpected stop.[3] Though thecollections do not offer any ego documents, they may be crucial for any scholars tracingsuch biographies in understanding the academic endeavours of the collectors.

Sustaining Inner Architectures, Articulating new Structures

One of the main aims of the MIDA project is to develop an online open-access database that

systematically catalogues, indexes and describes those files and holdings in key German

archives which relate to Indian history or the history of India-Germany entanglements.

Within the context of the ZMO archive, the Heidrich collections are ordered according to the

principle of provenance within the architecture of the archive. The MIDA database transforms this categorization according to the principle of pertinence by extracting such sources and ordering them thematically, with India as the focus.[4]

One of the objectives of the process of producing the database, has been to simultaneously mirror the architecture of the archive concerned and nonetheless showcase the India-specific sources. How can this be done effectively so that the database allows users to view the sources as they exist in the context in which they are embedded in the archival structure while simultaneously inserting them in a new systematic? This requires probing into the structure of the database and how the collections are effectively listed in it.

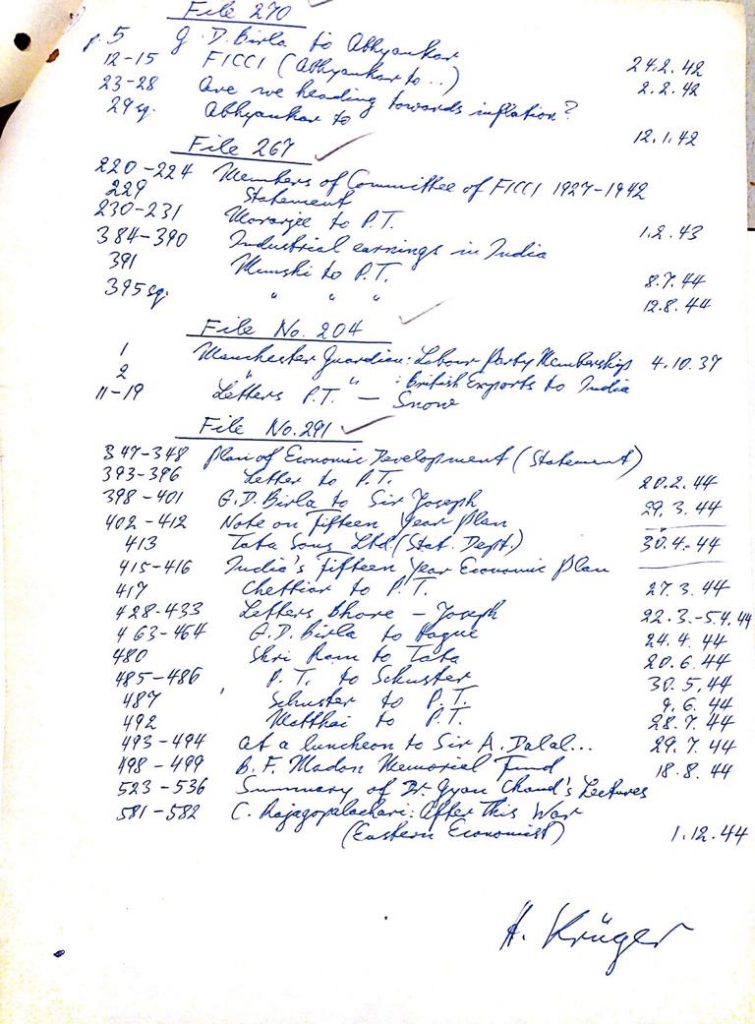

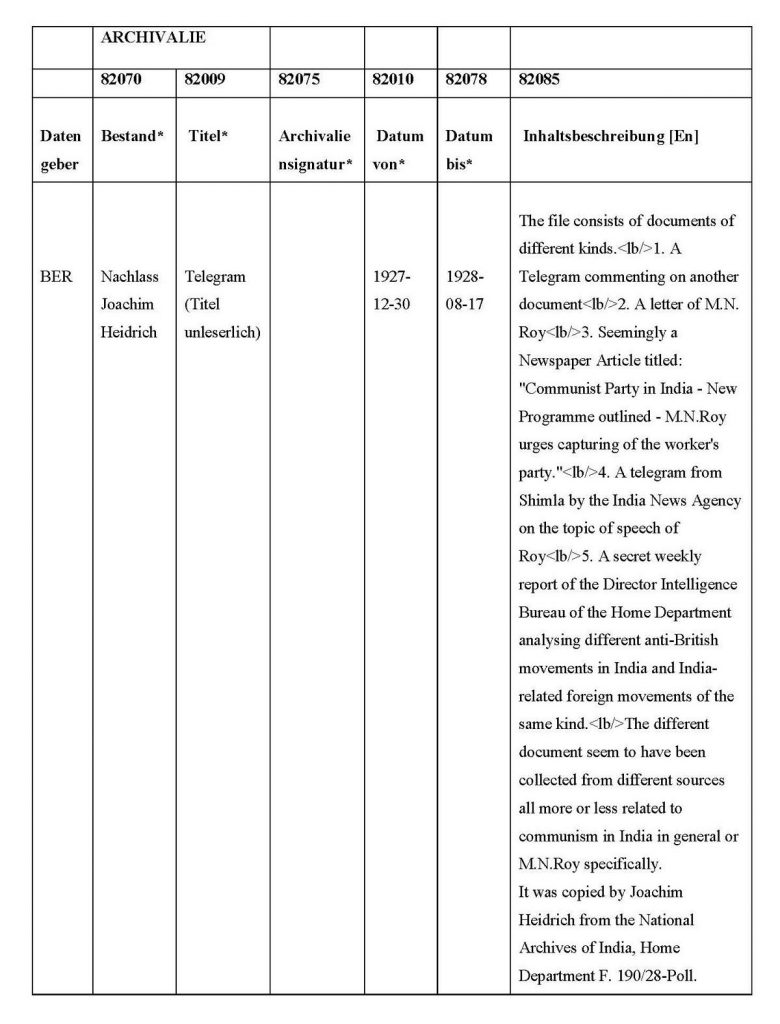

The database, whose structure became the guiding tool-kit for the students of the seminar while systematizing information from the Heidrichs’ collections, comprises three different levels of description– The ‘Archive’ field (Archiv), the ‘Holdings’ field (Archiv Bestand) and the ‘Files’ field (Archivalien). In the case of the Heidrich collections, there are two holdings described under the ‘Holdings’ field i.e. Nachlass Joachim Heidrich and Nachlass Petra Heidrich. The ‘Files’ field lists each individual file. The title of the file corresponds to the main title as listed on the first sheet of each group of pages that were carefully pinned together by the collectors. It is here that one often encounters photocopies of several documents (numerous files from Indian archives) which were placed together as one file by the collectors. Thus, although an individual file may in reality correspond to several photocopied files, these are nonetheless treated as a singular entity (Einheit) in order to sustain the ordering logic of the collectors. For example, Box 1.3 consists of a file (see figure 3), which is in fact a collection of varying documents that have been clipped together as a singular entity. The file has simply been titled as “Telegram (title illegible)” in the MIDA database entry. In the column titled ‘Description of Contents’ (Inhaltsbeschreibung [En]), however, one can see that the file consists of five different sources viz.

- A Telegram commenting on another document (not entirely legible or comprehensible)

- A letter of M.N. Roy

- A newspaper article titled: “Communist Party in India – New Programme outlined – M.N.Roy urges capturing of the worker’s party.”

- A telegram from Shimla by the India News Agency on MN Roy’s speech

- A secret weekly report of the Director Intelligence Bureau of the Home Department analysing different anti-British movements in India and India-related foreign movements of the same nature. The different documents seem to have been collected from different sources all more or less related to communism in India in general or M.N.Roy specifically.

Hence, in order to keep the organizing order undisturbed, the otherwise five different sources have been treated as a singular file in the database but they are also listed individually in the description field to give the user a most detailed view into the contents. At the same time, the exact source of the file is also incorporated in the description. The person making the entry mentions that the file was copied by Joachim Heidrich from the Home Department of the National Archives of India (NAI) beside the exact file number as it appears in NAI’s catalogue. In this way, the original source is also indicated to a user while re-placing the source in the new systematic of the database. In some cases, where visible in the form of official stamps of the archives (National Archives of India or NMML), the date when the file was copied by the collectors is also mentioned.

This post has attempted to engage users with the process of tracing, enlisting and indexing sources related to India from a private collection housed in the archive of the LeibnizZentrum Moderner Orient, Berlin. In doing so it has pointed to some of the methodological considerations involved when such sources, belonging to a given archival architecture, are extracted for being re-configured on a digital platform which has its own overarching structure and organisational logic. At the same time, it has shown how entangled archives (between the GDR and India in this case) intertwine with, and also reflect, the entangled life trajectories of the collecting historians. The main objective of the post has thus been to transparently share the ‘how’ of digital cataloguing as a process and the questions that arise when data is de– and re–configured in the midst of transforming ordering systematics.

Endnotes

[1] As an attempt to initiate critical discussions on this, a first step taken by the project is to organize a workshop especially dedicated to discussing the relationship between entangled histories and entangled archives. See: the announcement of the project’s international workshop in September 2018 (Link to be added here).

[2] See for example, Hecht, A. (ed.), “Enttäuschte Hoffnungen: Autobiographische Berichte abgewickelter Wissenschaftler aus dem Osten Deutschlands”, s.l.: Verlag am Park, 2008 and Idem, Die Wissenschaftselite Ostdeutschlands. Feindliche Übernahme oder Integration?, Leipzig: Faber und Faber, 2002.

[3] Hafner, A., “Petra Heidrich’s research work in the context of the development of South Asian Studies at the ZMO (1992–2000)”, in: ZMO Working Papers, 1, 2010, pp. 1–7.

[4] For more reflections on the Pertinence and Provenance principles see the Introduction to the MIDA Archival Guide (See the Introduction to the Online Archival Guide) and on the process of re-structuring through databases, also see, Bajpai, A., Heymann, J. and Suski, T., “Tracing India in German Archives: Entangled Pasts in the age of Digital Humanities”, in: South Asia Chronicle, 6, pp. 289–314.

Bibliography

Bajpai, A., Heymann, J. and Suski, T., “Tracing India in German Archives: Entangled Pasts in the age of Digital Humanities”, in: South Asia Chronicle, 6, pp. 289–314.

Hafner, A., „Petra Heidrich’s research work in the context of the development of South Asian Studies at the ZMO (1992–2000)”, in: ZMO Working Papers, 1, 2010, pp. 1–7.

Hecht, A., Die Wissenschaftselite Ostdeutschlands. Feindliche Übernahme oder

Integration?, Leipzig: Faber und Faber, 2002.

Hecht, A. (ed.), „Enttäuschte Hoffnungen: Autobiographische Berichte abgewickelter Wissenschaftler aus dem Osten Deutschlands“, s.l.: Verlag am Park, 2008.

Anandita Bajpai, IAAW, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029