By Vandana Joshi

Published in 2022

DOI 10.25360/01–2022-00022

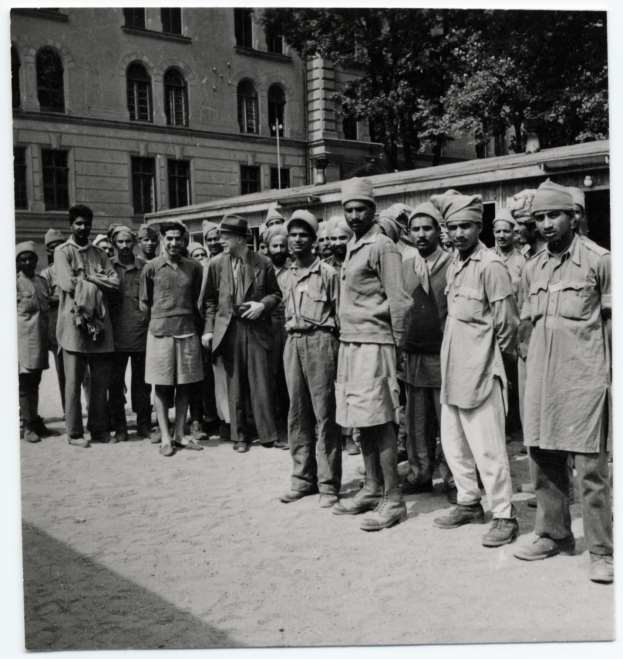

Image: A group of around 20–30 POWs are standing together with the visitor Dr. Exchaquetin what appears to be a courtyard in front of a larger building. Fig. 1: V‑P-HIST-01695–02 Annaburg. Stalag IV E, Visit of the delegate ICRC, Dr. Exchaquet, on 27 June 1941. Courtesy: Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (CICR).

Table of Contents

Diplomacy, Propaganda, Subversion and Psychological Operations (Psy-Ops) | Preparations of Subversion | Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Enters the Scene | British Nightmare | Projections of Welfare and Paternalism | Annaburg as the Epicentre of Subversion and the Raising of the Indian Legion (1941–43) | Prayer Rooms of Indian Captives | German Furtiveness | Recruitment Strategies | Postal Delays and Linguistic Diversity | Conclusion | Endnotes | Bibliography

This article uses some rare pictures and reports from the International Red Cross Archives to evaluate the diplomatic manoeuvres, psychological operations (psy-ops) and propaganda around British-Indian prisoners and Indian legionaries in WWII Germany from the perspective of experts from the International Red Cross Committee (CICR, French abbreviation), who were supposed to act as neutral observers. This source-base is then juxtaposed with visual and textual German and British sources to provide a larger context to British-German entanglements at the Annaburg prison camp in the non-combatant realm of soldiering and politicking during the Second World War in Germany.

Annaburg, seen on the cover photo (Fg.1),[i] was Stalag IV D/Z from May 1942 to April 1945. In a communication of 18 August 1942 from Berne, Switzerland, to the Foreign Office, London, it was stated that Annaburg Oflag IV E was to be known as Stalag IV D/Z. The CICR visitation report of 27 June 1941, however, called it Annaburg Stalag IV E.[ii] The German officialdom interchangeably used Annaburg Stalag IV E or Oflag 54 before renaming it Annaburg Stalag IV D/Z.

Why do we have these different sets of identi-fication for the same prisoners’ camp in the small Saxon castle-town of Annaburg? Does it indicate a state of flux in the camp site or could it have been a part of the German strategy to keep its character ambiguous during the period under consideration? Through a micro-study of Annaburg, an exclusive camp site for British-Indian prisoners in Germany, I will reflect on broader issues such as the use of deception, sabotage, subversion and intrigue by the Germans during the raising of the Indian Legion in the diplomatic circles.

Diplomacy, Propaganda, Subversion and Psychological Operations (Psy-Ops)

The European theatre of war was not just a combat zone, but also one of waging war through other means: diplomacy, propaganda, subversion, and psy-ops. Annaburg, a small castle-town in today’s Saxony-Anhalt, was a site for what the British perceived as the suborning of British-Indian soldiers. It thus became the nerve-centre of British-German entanglements. Signals of manipulations, deceptions, and intrigues produced ripples in the British Foreign Office, involving the Swiss Legation and the International Red Cross in the game of counter intelligence and welfarism from mid-1941 till the formation of the Indian Legion on German soil in early 1943.

Unlike Japan, which showed no obligation to the Geneva Convention of 1929 regarding the treatment of POWs, from early on, Nazi Germany agreed to make appropriate arrangements in accordance with the provisions of the Convention. The entry of the neutral Swiss agencies created conditions for a war of words and nerves between and across the British and German empires. This ‘war by other means’ was carried out through communications from British and German Foreign Offices, which in turn were supplied information by their respective war offices to the Swiss Legation and International Red Cross office in Berlin, Berne, London, and Geneva.

The Legation’s aim was to ensure the welfare of the prisoners through periodic visitations of the International Committee of the Red Cross delegates. The CICR team conducted inspections of health, sanitation, hygiene, spiritual and general living conditions in camps and directly interacted with inmates of Stalags (camps for ordinary prisoners), Oflags (camps for officers), Marlags (camps for interned mariners), Dulags (transit Camps), Heilags (transit camps for the wounded to be repatriated under the exchange programme), and, in some cases, Arbeitskommandos (labour detachments).[iii] The Swiss Legation and the International Red Cross became crucial mediators in addressing mutual grievances and transmitting information on the ground realities of camp life to the concerned belligerent empires.

This triangular network has left a trail of documents in French, German, and English that reflects imperial anxieties, diplomatic manoeuvres, intrigues, manipulations, mutual reprisals, intelligence, counter intelligence, military training, and delays in postal deliveries. Though such deliberations went far beyond the war as the Germans got busy with the destruction of records of the persecuted, the International Tracing Service with the documentation on and relocation of stateless and displaced (DPs) victims of Nazi atrocities,[iv] and the British with the repatriation of British-Indians, I limit my focus here to the crucial years of the formation of the Indian Legion between 1941 and 1943 to recreate the scenario of mutual fears and anxieties of the belligerent powers. The on-site records of Annaburg camp, its satellite camps and labour detachments (Arbeitskommandos) were destroyed towards the end of the war. Information about the working of the German Foreign Office and the Wehrmacht is therefore scattered and incomplete in contrast to British and Swiss communications, which are still preserved in their respective archives and will be used along with surviving German records to demonstrate imperial diplomatic entanglements during WWII.

Preparations of Subversion

Rommel’s first drive through North Africa in April 1941 resulted in the capture of the 3rd Motor Brigade comprising of British-Indian soldiers at the Libyan front. For the Germans these prisoners were not ordinary prisoners of the British Empire. They carried with them the potential for suborning sabotage and defections. Supporting the network of transnational revolutionaries in their anti-colonial struggles in Asia and Africa, and mobilising alien captives for setting up foreign legions, was neither new for Hitler nor for Germany. During WWI, Berlin became a centre of fermenting trouble in the colonies, harbouring Indian revolutionaries to disseminate anti-British propaganda[v] and establishing a propaganda prisoner’s camp on the outskirts of Berlin (Roy, Liebau, and Ahuja, 2011). This policy was pursued with more vigour and acumen in WWII. Collaborative forces of Ukrainians, Croatians, Dutch, Norwegians, Russians, and Arabs who were working for the Germans were now much better equipped with ideological (religious, national, or racial) motivation, modern arsenal, and military training.[vi] Raising an Indian Legion, however, presented its own hazards and challenges because of India’s distant location and the prisoners’ diversity (ethnic, religious, and linguistic).

Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose Enters the Scene

Subhas Chandra Bose arrived secretly in Berlin on 2 April 1941 (Hayes 2011, 25–29). His escape from house arrest in Calcutta, his adventurous journey to Kabul clad as a mute Pathan to cover his linguistic inability, his failure to get support from the Soviet Union, and his eventual arrival in Berlin with the help of the German embassy is a story often told with great relish in historical accounts both in India and Germany. That it would play a crucial role in the planning and formation of the Indian Legion was not known to Bose himself when he was in hiding in Kabul. His wish to reach out to Berlin for help was communicated by the German ambassador Hans Pilger to State Secretary Weizsäcker who expressed great interest in Bose despite receiving contradictory feedback on him. With the Italian embassy, which was equally keen to help, Bose left for Berlin carrying an Italian passport impersonating Orlando Mazzotta, an employee of the Italian embassy in Kabul (Kuhlmann 2003, 122–130).

Though Bose had to content with his rival Mohammad Iqbal Shedai, an anti-colonial insurrectionary, who was already active in Europe and was propagating the Indian cause through the Italian sponsored Radio Himalaya broadcasts, the German official circles were quick to accept Bose’s superior leadership qualities. Within a week of his arrival, Bose presented the Undersecretary of State, Ernst Woermann, a detailed plan for collaboration with the Axis. Woermann arranged a meeting with Foreign Minister Ribbentrop on 29 April 1942, to set up a Free India Centre, and the Azad Hind Radio in Berlin to disseminate anti-British propaganda. What proved more challenging for Bose was to set up a government in exile and to get a tripartite (Berlin, Rome, Tokyo) Axis declaration from Hitler for India’s independence.

Bose kept trying to persuade Hitler to commit but the latter remained evasive, first in the hope of negotiating peace with the British, and later because it made little strategic sense to him without backing the declaration up with military action. When Bose was finally able to meet Hitler in person on 29 May 1942, he pointed to the immense distance between the two locations and contrasted it with Japan’s geographical proximity, which seemed more favourable. He thought it would be foolish to make a declaration about India (Toye 1978, 68–69). However, he was ready to help with all possible means when it came to propaganda and psy-ops. He was quite certain that it would be a successful propaganda strategy and there would be a pay-off in the game of deception and psy-ops rather than in an actual anti-colonial military operation. When the moment arrived, he planned a safe exit strategy for Bose.

British Nightmare

The British were haunted by the spectre of quislings, renegades, traitors, legionaries, communists, and nationalists during this period (1941–43) and thereafter. British intelligence sources estimated that out of 12,000 Indian prisoners detained in German camps, the number of active members of the 950th Regiment at no point exceeded the mark of 3200 This British source contains a brief sketch of 4 August 1945 on Indian collaborationist activities in Germany, France, and Italy, and in particular, a reference to the Indian Legion.[vii]

Although even these legionaries never engaged in an active anti-colonial combat, their sheer existence along with the Free India Radio (Azad Hind Radio) broadcasts, and their eventual arrival in Switzerland kept the British on their toes much after the liberation of the camps. Germany became a playground for British anxieties, making the Indian POWs an object of incessant allures, suspicion, surveillance, reprisals, and loyalty testing.

The German efforts to woo Indian captives for propaganda work began already in North Africa. In his anecdotal account, the leading convert and recruiter of the Indian Legion, Mangat Singh, contrasted British officers’ racism and arrogance towards Indian soldiers to Rommel’s charm and modesty in personally coming to El Mechilli fort to meet them after their surrender on 8 April 1941. Mangat reminisced in his memoirs how a smart and sturdy German officer alighted from his moving Volkswagen and advanced towards them. He welcomed them with the words, “Good Morning to you, gentlemen! Thank you very much for the good fight you gave me. You are all my guests now. Excuse me, I am in a hurry. I must get going. Please remember me through my men, if you ever have any difficulty” (Mangat 1986, 31–33). He went on to praise this ‘smart officer’, who he later realized was none other than the “Desert Fox” Erwin Rommel himself, for his brilliance and accomplishments. In a footnote, he further contrasted Rommel’s behaviour with that of General Eisenhower of the Allied Expeditionary Forces, who had refused to shake hands with his enemy captives in a similar situation. Twenty-seven Indian captives were flown in from Benghasi to Berlin while the rest were transported by boat through Naples to Genoa and then by train to Annaburg.[viii]

Projections of Welfare and Paternalism

While the transportation of selected potential legionaries from different European destinations to Annaburg was already underway, the Foreign Office, Berlin, received a communication from the American Embassy in August 1941 on behalf of the British government. Drawing the attention of the “appropriate German authorities”, it requested that adequate provisions be made to cater to the prisoners’ special needs. It stated that besides warm clothing and heating, it would be appreciated if special arrangements regarding their religious beliefs and customs as well as the food and its preparation could be made. It also recommended housing officers in a separate accommodation and ensuring that other privileges such as work and pay would correspond to their rank.[ix]

Annaburg as the Epicentre of Subversion and the Raising of the Indian Legion (1941–43)

Already before this communication, the Annaburg castle-complex was being prepared to welcome British-Indian captives. The first visitation report of the International Red Cross Committee (CICR) gives us insightful information on this. In this section, I will dwell on this and subsequent reports on Annaburg to highlight Germany’s preparation for propaganda and psy-ops.

After stating the geographical coordinates of this Baroque style castle and its history as a garrison for young German NCOs (Non-commissioned Officers) and then a Stalag for Serbian prisoners until mid-May 1941, the CICR report moved on with details on Indians. On the visitation day of late June, it found 1200 Hindous including 40 officers, captured from the Libyan front, occupying the three-storied villa within the castle premises. The villa had the capacity to house 2,200 inmates, was well-lit and ventilated, and its huge rooms were furnished with three-tier bunk beds of which only two were in use. The sanitary and hygienic conditions were found to be excellent.

In the courtyard, there were five additional barracks housing prisoners of other religious denominations. Overall, there were 596 Mohametans, 200 Sikhs and 4 Brahmanes and the rest Hindous.[x] The report dwelled on how much free room there was in the villa for common activities, like a dining hall, a kitchen with a separate stove for Hindous and separate prayer rooms for different faiths. The prayer rooms aroused the curiosity and admiration of the report’s author, Dr. Exchaquet, which is testified by the photographic collection of the day to which I shall turn now.

Curiously, most captions of these photos state the location as “Altenburg” Stalag IV E but the date of the photo shoot is the same as that of Dr. Exchaquet’s visitation report of “Annaburg” Stalag IV E, namely 27 June 1941. Just one picture of the captives (Fig. 1 cover picture), carries the caption “Annaburg. Stalag IV E” which shows Dr. Exchaquet talking to the prisoners. The visitation schedule plan of several camps in Saxony around this time allocated one day to each site. Moreover, Altenburg at this time housed no Indian captives and did not have barracks like these. I, therefore, go with the assumption that pictures of the courtyard and prayer rooms were taken on 27 June 1941 during Dr. Exchaquet’s visit to Annaburg and not Altenburg.

Prayer Rooms of Indian Captives

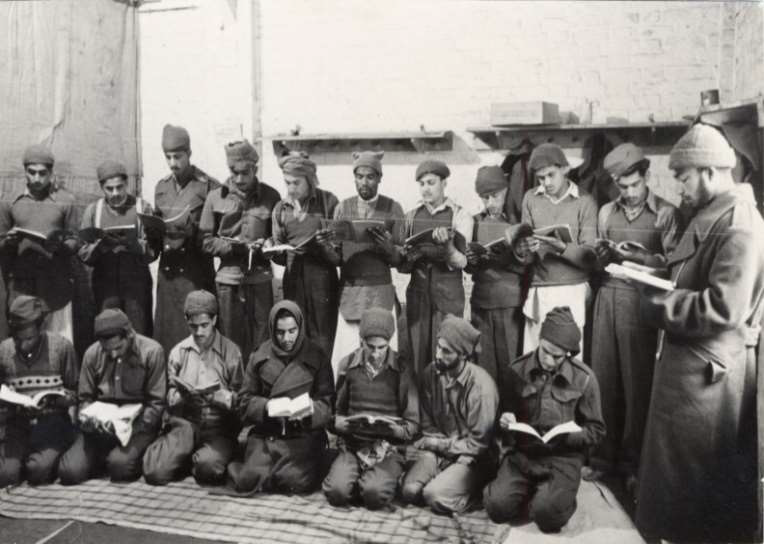

Altenburg (Annaburg?) Stalag IV E, prisoners of war camp. Prisoners of war going to pray.

Courtesy: CICR Photo Archive.

This is the entrance of one of the prayer rooms. It clearly shows the Annaburg castle in the background – as in Fig. 1 – but the caption reads “Altenburg”. The devotees arranged their shoes in neat rows at the doorstep before entering the prayer room. Dr. Exchaquet was quite impressed with this and even mentioned in the report that the devotees roamed around bare foot in silence inside the mosque.

Fig. 3 captures a Namaz rendition in progress in this interior of the prayer room we saw in Fig. 2. All captives are seen holding the holy Quran and reading it aloud. The walls are bare and the front row indicates the typical seating posture while rendering the Namaz.

Fig. 4 is especially illustrative in its details. In this makeshift Gurdwara, the house of worship of the Sikhs, their holy book, Guru Granth Saheb is covered in a beautifully patterned cloth. The holy book itself is placed on an alleviated platform covered in a spotless white sheet on which vases with flowers can be seen. Above the platform, hangs an equally decorative canopy. While the Granthi (ceremonial leader) is chanting from the Guru Granth Sahib, the devotees are listening to him quietly. Pictures of various Gurus adorn the wall on the right along with the Nishan Saheb, their holy symbol. Next to it, we can see a jhanjh and a dholak (percussion instruments) which accompany a harmonium (possibly kept inside the wooden box in the left corner below the window). These instruments and the decor are intrinsic to the setting up of a Gurdwara. It brings back to my mind a Sikh captive’s sound recording from WWI. After praising the Germans in this propaganda camp (Halbmondlager, Wünsdorf), he said “if they thought of us as them, they would have honoured our house of worship.” He was alluding to the missing cover for the Granth Saheb which the Germans did not bother to procure for the prayer room (Mahrenholz 2011, 201).[xi] The Germans in WWII seemed to have learnt the art of persuasion from their previous experiences with Sikh soldiers and their specific requirements related to their rituals.

A close reading of both the text and the picture collection of the CICR sources clearly reveals that Annaburg’s castle-complex was being prepared as a model POW camp to host British-Indian captives. The prisoners’ profiles indicate that there were several highly accomplished soldiers and officers among them, a carefully chosen and suitably inspiring selection for propaganda and recruitment purposes. Coming, as this evidence does, from a Swiss delegate and CICR evaluator of prisoners’ health and well-being, namely Dr. Exchaquet (or the unknown cameraperson S.N.), it contains vital insights into the art of persuasion Germans were practicing on Indian captives. The graphic textual and visual details are alluring, assuring, comforting, and promising to even a contemporary observer such as the author. Dr. Exchaquet liberally used terms such as remarkable, impeccable, well-kept and ventilated for the complex, which he thought was rarely the case in prisoners’ quarters. When it comes to the visual collection, we are not certain whether he submitted his own collection to the archive because his name does not figure as the photographer on record. As can be observed in Fig. 1, Dr. Exchaquet himself carried a camera which he is holding in his left hand.

The report also noted a wish list featuring items such as winter clothing, indoor games and balls for outdoor sports, and a change of camp in winters due to the harsh climate. The Mohametans sought allowance to offer Namaz at 23.00 hours. The Hindus complained about the food not being suitable to their vegetarian palate.[xii] The memoirs of captives and visitors’ recount the concern that was raised over the food. Soon enough, Red Cross parcels were arranged for them and gardening of seasonal salads and vegetables started at the camp site as noted in the next report. The inmates requested for books in English as 50 percent of them read English. Doctors requested for medical journals.

It is quite obvious from this description that the camp did not distinguish between officers and soldiers and this was done for a strategic purpose. The mixed nature of the camp, it was thought, would facilitate recruitment. Similarly, the labels Oflag and Stalag were used interchangeably by the Germans to send confusing signals outwards.

On 16 October 1941, Ribbentrop gave Bose a go ahead for his recruitment drive in camps and soon after to raise an army (Normann 1997, 174). Bose visited Annaburg and Frankenburg in December 1941. One of the first enthusiastic converts from Berlin, wrote in his memoirs that the inmates did not believe that it was Bose himself who was standing before them and the NCOs remained totally unresponsive to his call (Mangat 1986, 75–79). Once his identity was verified through a reliable source, the author says that he was able to recruit 1000 captives but the number seems highly unlikely, as only one propaganda company could be raised. Bose realized that ordinary men were more susceptible to his charm than the NCO. Thus, on 13 January 1943, 2 convoys of Indians were brought to Germany after 2 and a half days of travel in goods trains, which were only partially heated. Many prisoners only wore pants (or underpants), shirts and a jacket. It seemed that the men had suffered a lot from cold, eight of them had frozen toes and one was still in the infirmary.[xiii] After such an arduous journey and relatively poorer nourishment, as the CICR report tells us, the lodging in Italian captivity, a failed attempt by Shedai to raise an Indian legion in Italy, the far superior arrangements in Annaburg seemed to have paid dividends. The number of volunteers rose dramatically starting with the Sikh regiment signing up as the first enthusiastic converts.

The Annaburg camp underwent a major transformation if we go by the CICR report filed on 15 May 1943.[xiv] It had enrolled 4323 Indians, of whom 864 were Sikhs, 2136 Hindous, 9 Bouddhists, 1214 Mahometans and 100 Chretiens. The total was broken down professionally to 8 officers, 538 NCOs and 3777 men, 3 doctors, and 6 paramedics. Of these, just 1587 captives stayed inside the camp while the rest were sent to labour detachments. 32 detachments returned to the camp every evening after work. Three external detachments of 82, 10, and 2736 (total 2828) remained stationed in their labour detachment camps.

The CICR report went on to note that there was a vegetable garden where fresh seasonal vegetables and salads were grown by 10 men. The rice came from Geneva. Besides, other men were engaged in cooking, tailoring, mending of shoes, socks, and stockings, the hair salon and latrine maintenance. Every prisoner had a new “battle-dress”, a jacket and new boots. The state of health and discipline was excellent with no reported deaths. The library was equipped with 800 books, the British prisoners’ newspaper The Camp was banned. Prisoners could take language and writing lessons under an Indian professor. The prisoners attended film screenings in the theatre, had a chessboard, musical instruments, footballs. They went out for walks in groups of 5–600 men. Several prisoners were sent out to work in surrounding areas and returned to the camp for their afternoon and evening meals.

It was between the two reports of 27 June 1941 and 15 May 1943 that selections, recruitment, and finally military training took place, first in Meseritz, then Frankenberg and ultimately Königsbrück. The camp authorities designated them as ‘external labour detachments’ of Annaburg to maintain secrecy over the military training they were receiving from the Wehrmacht. Keeping it a secret, however, turned out to be quite a challenge as we shall see in a while.

German Furtiveness

Annaburg and these training centres were frequented by Bose throughout 1942. Annaburg became the epicentre for loyalty testing, combat fitness, rumours, intense propaganda and counter-propaganda, as pressure mounted on the captives to decide between the Legion and continued captivity. Anxieties swelled up in the German officialdom on how the recruitment drive and training could be kept a secret. Surviving holdings in the German Foreign Office Archives reflect the diplomatic tension in the letters that were exchanged between Germany, Switzerland, and Britain during this period.

From mid-1942 the Swiss Legation sent repeated requests to Foreign Office, Berlin, on behalf of the British, who suspected some camps of harbouring legionaries, to schedule visitations to the camps, especially Annaburg IV D/Z, Colditz Oflag IV E, and Mühlberg IV B. On 3 July 1942, the Swiss Legation was clearly told that so far as Annaburg was concerned, the visit permission could not be granted for the time being. However, Colditz and Mühlberg could be visited. On 17 June it was told telephonically that British-Indians were transferred from Colditz to Annaburg. So, only Mühlberg IV B could be visited but not Königsbrück, Ringbaum and Frankenberg. When the Legation reminded the Foreign Office, Berlin, that Art. 86 of the Geneva Convention authorized them to visit all POW camps, it gave various excuses such as first the outbreak of epidemic typhus, then the British ill-treatment of German captives in South Africa and then the awaited clearance from prison authorities. The Legation requested the Foreign Office, Berlin, to allow them to visit IV E Colditz Oflag/ Zweiglager, instead of Colditz IV C on 17 July 1942.[xv] The Swiss Legation informed the British Ministry of Foreign Affairs that Camp IV E, in question, was named Colditz Oflag IV E and had a mix of Indian officers and men.[xvi]

In August 1942, the Swiss Legation was finally told that Königsbrück was not a prisoner’s camp but a military training centre and therefore visitation could not be granted. The Swiss Legation managed to send a team and communicated a short report from Berne to the British Foreign Office, London, on 20th November 1942 on Annaburg, by when it was renamed IV D/Z. This overcrowded camp had water scarcity and insufficient heating and toilette facilities. The Man of Confidence (representative of the prisoners) had to send Red Cross parcels to Frankenberg and Königsbrück, which he believed were Legion camps. German authorities stated that Frankenberg no longer existed and that the latter was a labour camp like any other.[xvii]

The frustration of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, London, shows clearly in its communication to the Swiss Legation on 3 June 1943: “Regarding Stalag IV D/Z Annaburg, it was actually not possible in the period in question to visit the Indian POWs. It is to be regretted that owing to the contradictory statements of the officers who spoke with the Swiss Delegation, the impression has been formed that it was the intention to create special difficulties for the delegates; the attitude of the officer was brought about by the fact that he was not sufficiently informed of the circumstances”.[xviii]

We also know from the May 1943 CICR visitation report of Annaburg that inmates of external labour detachments were not available at the time of the inspection, one of which numbered 2736. This external labour detachment, I suggest, was in fact not a labour detachment at all but the Indian Legion where prisoners were being secretly trained at Königsbrück. By the time the next visit took place on 15 November 1943, the total number at Annaburg came down from 4323 to 2779 of which 1801 were present at the camp, 37 in the infirmary, 22 in hospital, 4 doctors and 8 medical orderlies. There was now just one chapel for all faiths.[xix]

Recruitment Strategies

The recruitment strategies ranged from allurements such as the ones evident in CICR reports, well-lit, heated and ventilated living rooms, well-decorated prayer halls, rice from Geneva, fresh salads and vegetables from the garden, to appropriate cooking arrangements for each religious denomination.

Bose’s recruitment strategy was customized according to the type of prisoner. For example, when he wanted to recruit the RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps) doctor, Captain Mazumdar, in the summer of 1942, he acted like a perfect gentleman playing the polite, patriotic card in the meeting. Mazumdar was picked up in a Mercedes from his camp and brought to Berlin. Bose spoke to him in Bengali, their mother tongue, to establish a quick rapport with a complete stranger and switched to English when he approached the subject, “Do you know why you are here? We are forming the Indian Legion and I want you to join us”. Mazumdar replied, “I cannot and shall not. I was taught a promise once made, you have got to abide by.” Bose left the room with the words, “I do not think we should meet again”. Mazumdar was back to Colditz next morning, this time travelling in 3rd class compartment. When the interviewer of the Sound Archive, Imperial War Museum, asked him, “What was Subhash Chandra Bose’s demeanour?”, Mazumdar replied, “Very polite, like one Bengali talking to another. I was very impressed, he could make you do things. Though he was a bit annoyed he did not show it.” “Did he threaten you?” asked the interviewer, “No, but I was promised many things by the Germans before that too”.[xx]

Bose left the intimidation and reward game to be played by the Gestapo before and after his encounter with Mazumdar, like he may have done with other prisoners of the latter’s stature. British intelligence was very curious to know the details of the meeting, then and several years later, Mazumdar testified. On 3 December 1943, Major Tucker, an erstwhile colleague of Mazumdar, made a statement to Lt. Col. H. J. Phillimore of MI2 and in-charge of the POWs about Mazumdar. He believed that Germans knew that this officer had been a member of the Free India movement before the war and, in consequence, every form of pressure was put on him and every sort of inducement held out to him to persuade him to join the Indian Legion. After the Berlin trip, he was put in solitary confinement, forbidden to practice, and subjected to many indignities. He went on a hunger strike for 14 to 18 days. The Germans became frightened and sent him to another camp.[xxi]

Major Tucker did this to pre-empt Mazumdar being accused by some British officers of playing a double game which indeed his British inmates at Colditz believed, therefore mocking him as the “Gandhi chap”. Tucker thought that Mazumdar stuck out against great pressure from Germans. He had known Mazumdar before his capture and thought him to be a good man and a good doctor.[xxii] This statement was circulated to the concerned intelligence officer, yet Mazumdar’s troubles were far from over, if we believe his own testimony.

When Bose did not have much success with the NCOs during his first visits to Annaburg in December 1941, he devised another strategy. He got Italy to send prisoners straight to the training grounds so their fresh and uncorrupted minds could be influenced directly. Girija Mookeerji, one of his associates, reminisced, “standing very erect under a tree and talking to the soldiers for hours, I saw how the audience was coming under his spell…when he had finished they acquired new life, new animation, new excitement…Dozens now asked to be enrolled” (Bose 1982, 201). Major Mackay, a British captive who was visiting a hospital in the proximity of Königsbrück for dental treatment, managed to talk to some recruits who told him that some of the NCOs were promoted to German commissioned rank.[xxiii] What Mackay thought was a bribe was merely an incentive and reward for loyalty to Bose. Fresh batches of NCOs arrived straight to Königsbrück from Italian captivity. Bose made prophetic speeches to inspire them such as: “The English are like the dead snake which the people are afraid of even after its death. There is no doubt that the English have lost this battle. The problem is how to take charge of this country…We are young and we have a sense of self-respect. We shall take freedom by the strength of our arms. Freedom is never given it is taken” (Bose 1982, 201).

Apart from exercising his charms on the rank and file, he also played with their psyche to get compliance. Captain Mazumdar told another Colditz escapee that some captives from Annaburg told him that they heard shots, were shown blood stains and were then invited to sign a document of some sort under the threat of being immediately shot. Very few signed and then they spotted that the executions were staged for their benefit.

Germans’ racial ideology was diluted to allow the recruits free access to local German women. Abundant supplies of Red Cross parcels containing cigarettes and chocolates was an easy way to win local women’s company. Whether at Frankenberg, Königsbrück, Holland, or the Altantic Coast, crossing the racial line by the legionaries irked the German officers, local populations, and trainers alike, but the high command tolerated it. Some marriages were reluctantly approved such as those of middle-class professionals recruited for propaganda work. Some others ended badly for the mixed offspring in post-war Germany.[xxiv] However, seen from the perspective of the military culture in wartime Germany, racial laws were not applied so indiscriminately. German soldiers were allowed to rape and pillage in the occupied East. The local women witnessed a range of behaviour patterns from the military from rape and sexual slavery to more stable relations based on monetary and other incentives in kind including protection from everyday abuse. To bring back order, brothels were set up later which housed local women of all racial backgrounds. While the Nazi officialdom always warned the soldiers against establishing sexual contact with local women (Rassenschande as it was called), soldiers were seldom punished for these acts of indulgence with the so called “racially inferior Easterners” or even Jewish women for that matter.[xxv] The same ambiguity could be seen in cases of race mixing with the Japanese and Italians, who confronted the German officialdom when they saw racial laws being applied to them (Krebs 2015, 217–241; König 2018).

Postal Delays and Linguistic Diversity

One thread that ran across all Red Cross visitation reports to camps and labour detachments was the slow or non-existent flow of post to prisoners. Prisoners said that they regularly sent letters home but did not get replies. The postal exchange and censorship remained a source of constant displeasure and anxiety for the captives. The reasons could be multiple: the High Command’s order to stop air mail from Egypt, the insulation of camps from external influences (such as the banning of the British newspaper The Camp), and reprisal for disobedience. These were all part of the recruitment and disciplining strategies.

The most interesting of them, however, was the following: According to the Geneva convention, POWs could write in their mother tongue but the German OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, High Command of the Army) issued an order to the ranks banning letter writing in regional languages. Sure enough, the British government made a representation to the Swiss Legation evoking Article 56 of the Geneva Convention. The German authorities retorted that there was no breach of postal regulations on their part. India had over 200 languages and the interpreters were simply not available for each! They could only write letters in certain approved languages. The main problem was: What would they censor if they could not understand the content? The overwhelming diversity of Indian languages seemed to have exhausted the anthropological reserves of the German empire. Their frustration at the inability to read the captives’ minds marred the prospects of controlling their minds.

In comparison, the British collected quarterly censorship reports on mails exchanged between soldiers and their kin throughout the war.[xxvi] This shows just one dimension of generations of connections between the empire and its soldiers. This, among other things, goes to explain why despite every possible incentive, the large majority of captives remained loyal to the Raj.

Conclusion

The politics of expediency both Hitler and Bose played with each other may not have been a military success but the psy-ops and propaganda turned out to be a nightmare for the British intelligence agencies. Bose in his propaganda offensive throughout late 1942 and early 1943, claimed to know more about events in India than its government had made public and would include coded instructions as if to a wider network of his agents there. In his speeches aired from Berlin, he would talk about the dropping of paratroopers, giving circumstantial details and urging peasants to help them, or warn the police and soldiers that one day they would have to answer to the Free India government for their criminal support to the British (Toye 1978, 69).

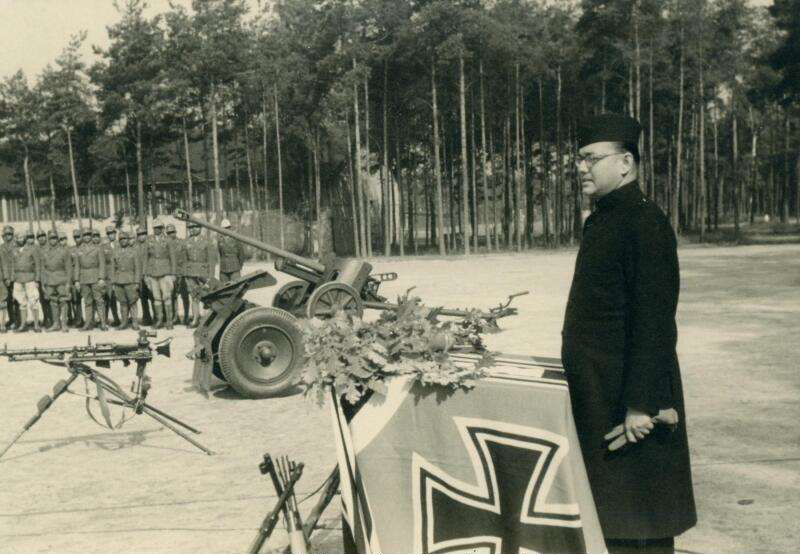

Under the shroud of confusion, mis-communications, misinformation, undelivered prisoners’ post, and delayed CICR visits to Stalags housing British-Indian prisoners, we see Subhash Chandra Bose saluting the Indian Legion soldiers dressed in their captors’ uniforms, marching in columns at Königsbrück in the autumn of 1942.

Interestingly, Bild 101I is from the Record Group of Propaganda-kompanien der Wehrmacht- Heer und Luftwaffe, which has a collection of 21850 photographs in the Bundesarchiv dealing with various propaganda companies of the German army.

In the rare photograph above, a gleeful and proud Subhas Chandra Bose is seen addressing the first propaganda company of the Indian Legion at Königsbrück amid much jubilation, the oath taking ceremony, and all the rituals of initiation that went with the formation of yet another foreign legion on German soil. While presenting the tricolour with the springing Tiger embossed on it, Bose told the soldiers: “Your name will be written in golden letters in the history of free India. Every martyr in this holy war will have a monument there. I shall lead the army when we march to India together” (Bose 1982, 202). When Bose uttered these words, he had already started looking eastward for an actual armed resistance to the British Raj. In the end, Germany was a mere laboratory for his experiment. In his frequent visits to Königsbrück in 1942, Japanese observers could be sighted. The oath taking ceremony in 1942 was attended by the Japanese press and Colonel Yamamoto Bin, the Military Attaché from the embassy in Berlin. Bose was able to demonstrate to the Japanese that he could raise an army from captives. On 8 February 1943, Bose departed from Kiel on a German U‑boot for the Far East, where the number of captives was much larger and the chances of actual combat real. His departure was kept a guarded secret. In April, the three battalions of Indian Legion were absorbed into the German Army by the name of the 950th Infantry Regiment and deployed to guard the Western Front.

The above picture shows the proceedings of an elaborate ceremony to celebrate Bose’s provisional national government in exile. The function took place in Hotel Kaiserhof, Berlin, in November 1943. It was attended by high profile German dignitaries, and ambassadors from Italy and Japan. The founder of the exile government Bose, ironically, can only be seen in a picture frame on the wall while his speech played on a record player.

Endnotes

[i] While the photo collection is cited as CICR, (Comité International de la Croix-Rouge) the reports go as ACICR (Archiv de Comité International de la Croix-Rouge). Both are located on the same premises in Geneva. I am thankful to Navina Lamba for helping me with these reports written in French.

[ii] Altenburger, Andreas, Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschafts-Stammlager (M‑Staleg oder Stalag), n.d., http://www.lexikon-der-wehrmacht.de/Gliederungen/Kriegsgefangenenlager/Stammlager.html. (Last accessed on: 01.12.2020).

[iii] This correspondence is archived in all three countries. In German Foreign Office Archives (PAAA) in Berlin, the National Archives (TNA) and India Office Records (IOR) in London and the Office of the International Committee of the Red Cross (CICR) in Geneva.

[iv] See: Joshi, Vandana, “Memory and Memorialisation, interment and exhumation, propaganda and politics during WWII through the lens of International Tracing-Service Collections”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 12 pp. www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/memory-and-memorialisation-interment-and-exhumation-propaganda-and-politics-during-wwii-through-the-lens-of-international-tracing-service-its-collections/.

[v] For Germany’s role in aiding and abetting anti-colonial activities of the Indian, Persian, and Algerian-Tunisian independence committees against the British, French, and Russian empires respectively during the First World War through her ‘programme for revolution’, see: Jenkins, Jennifer, Heike Liebau, and Larissa Schmid, “Transnationalism and Insurrection: Independence Committees, Anti-Colonial Networks, and Germany’s Global War”. Journal of Global History 15 (2020): pp. 61–79.

[vi]Among the more recent works see David Motadel (2014) for German subversive activities in the Islamic world. Foreign Office Berlin made concerted efforts through policies and propaganda work in the Muslim war zones from recruitment and spiritual care to ideological indoctrination of tens of thousands of Muslim volunteers who fought in the Wehrmacht and the SS. For Danish, Swedish and Swiss Waffen SS volunteers see: Gutmann, Martin R., Building a Nazi Europe: The SS’s Germanic Volunteers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017; Ibid., “Debunking the Myth of the Volunteers: Transnational Volunteering in the Nazi Waffen-SS Officer Corps during the Second World War”. Contemporary European History 22, no. 4 (2013): pp. 585–607.

[vii] TNA WO 208/802. This file contains a brief sketch of Indian collaborationist activities in Germany, France and Italy in particular reference to the Indian Legion, written on 4.8.1945. The Indian Legion was later named the 950th Regiment of German Army once it was deployed outside Germany.

[viii] According to Mangat, one of those captured at El Mechilli, twenty-seven prisoners were selected to fly to Sicily and he was one of them. On the 17th of May the party was interviewed again their questions were mainly centred around politics and Mangat found himself to be “weak” as far as his answers were concerned. They then selected 8 men to fly with them to Berlin while the rest reached Berlin by train on the night of 19/20 May 1941. He wrote about the prisoners being split up and rearranged in groups time and again. The advance party was supposed to advise the Germans on the food habits and customs of Indians. See: Mangat 1986, pp. 36–37.

[ix] PAAA R40742

[x] The spellings of various religious groups of Indians have been reproduced as they exist in reports of ACICR furnished in French (or ICRC in English).

[xi] The German version of this article was republished by MIDA in 2020. See: Mahrenholz, Jürgen‑K., “Südasiatische Sprach- und Musikaufnahmen im Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2020): 19 pp. https://www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/suedasiatische-sprach-und-musikaufnahmen-im-lautarchiv-der-humboldt-universitaet-zu-berlin/.

[xii] ACICR, C Sc Stalag IV E, 27.06.1941

[xiii] ACICR, C Sc, Stalag IV D/Z, 15 May 1943

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] PAAA R 40985. This file on British-Indian prisoners was maintained for a period from July 1942 to November 1942 and gives telling details of the war of words.

[xvi] PAAA R 40985

[xvii] TNA WO 224/14B TNA Annaburg 3

[xviii] TNA WO 224/14 B

[xix] ACICR, C Sc, Stalag IV D/Z, visit on 15.11.1943

[xx] Imperial War Museum (IWM), Sound Archive, 16800. For more on Mazumdar and the life of South Asian POWs in Annaburg see: Joshi, Vandana, “The Making of a Cosmopolitan Jangi Qaidi: A Leaf from Sohan Singh’s Prison Notebook written in Annaburger Stammlager D/Z in German captivity during the Second World War (1942- 45)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2020): 11 pp. https://www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/the-making-of-a-cosmopolitan-jangi-qaidi/.

[xxi] TNA, WO 208/808

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] Ibid.

[xxiv] See: Günther, Lothar, Von Indien nach Annaburg. Berlin: Verlag am Park, 2003, pp. 48–49.

[xxv] Gender, race and sexuality in wartime is a burgeoning field of new military history, and we now have ample literature available on the theme. See: Herzog, Dagmar (ed.), Brutality and Desire: War and Sexuality in Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009; Röger, Maren, Wartime Relations. Intimacy, Violence, and Prostitution in Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020; Joshi, Vandana, “Soldier’s Morale and War Wife’s Morality: Gendered Images of Righteousness and Citizenship in Nazi Germany”. Feministische Studien 2 (2015): pp. 229–245; Timm, Annette, “Sex with a Purpose. Prostitution, Venereal Disease, and Militarized Masculinity in the Third Reich”. Journal of the History of Sexuality 11, no. 1/2 (2002): pp. 223–255.

[xxvi] IOR contains a massive collection of the censured letters that provide us a window to prisoners and soldiers life.

Bibliography

Bose, Mihir. The lost Hero. London: Quartel Books, 1982.

Günther, Lothar, Von Indien nach Annaburg. Berlin: Verlag am Park, 2003.

Gutmann, Martin R., Building a Nazi Europe: The SS’s Germanic Volunteers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017

——–, “Debunking the Myth of the Volunteers: Transnational Volunteering in the Nazi Waffen-SS Officer Corps during the Second World War”. Contemporary European History 22, no. 4 (2013): pp. 585–607.

Hayes, Romain. Subhash Chandra Bose in Nazi Germany: Politics, Intelligence and Propaganda, 1941–43. London: C. Hurst & Co., 2011.

Herzog, Dagmar (ed.), Brutality and Desire: Brutality and Desire: War and Sexuality in Europe’s Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

Jenkins, Jennifer, Heike Liebau, and Larissa Schmid, “Transnationalism and Insurrection: Independence Committees, Anti-Colonial Networks, and Germany’s Global War”. Journal of Global History 15 (2020): pp. 61–79.

Joshi, Vandana, “Soldier’s Morale and War Wife’s Morality: Gendered Images of Righteousness and Citizenship in Nazi German”. Feministische Studien 2 (2015): pp. 229–245.

——–, “Memory and Memorialisation, interment and exhumation, propaganda and politics during WWII through the lens of International Tracing-Service Collections”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 12 pp. www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/memory-and-memorialisation-interment-and-exhumation-propaganda-and-politics-during-wwii-through-the-lens-of-international-tracing-service-its-collections/.

——–, “The Making of a Cosmopolitan Jangi Qaidi: A Leaf from Sohan Singh’s Prison Notebook written in Annaburger Stammlager D/Z in German captivity during the Second World War (1942- 45)”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2020): 11 pp. https://www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/the-making-of-a-cosmopolitan-jangi-qaidi/.

König, Malte, “Racism Within the Axis: Sexual Intercourse and Marriage Plans Between Italians and Germans, 1940–3”. Journal of Contemporary History 54, no. 3 (2018): 508–526. DOI 10.1177/0022009418768852.

Krebs, Gerhard, “Racism under Negotiation”. In: Rotem Kowner and Walter Demel (eds.) Race and Racism in Modern East Asia: Interactions, Nationalism, Gender and Lineage. Leiden: Brill, 2015, pp. 217–241.

Kuhlmann, Jan, Subhas Chandra Bose und die Indienpolitik der Achsenmächte. Berlin: Verlag Hans Schiler, 2003.

Mahrenholz, Jürgen‑K., “Recordings of South Asian Languages and Music in the Lautarchiv of the Humboldt Universität zu Berlin”. In: Franziska Roy, Heike Liebau, and Ravi Ahuja (eds.) „When the war began we heard of several kings“. South Asian Prisoners of World War I Germany. New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011, pp. 187–206.

——–, “Südasiatische Sprach- und Musikaufnahmen im Lautarchiv der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin”. MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2020): 19 pp. https://www.projekt-mida.de/reflexicon/suedasiatische-sprach-und-musikaufnahmen-im-lautarchiv-der-humboldt-universitaet-zu-berlin/.

Mangat, Gurbachan Singh, The Tiger Strikes: An Unwritten Chapter of Netaji’s Life History. Ludhiana: Gagan Publishers, 1986.

Motadel, David, Islam and Nazi Germany’s War. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Normann, Rodrick de, “Infantry Regiment 950-Germany’s Indian Legion Source”. Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research 75, no. 303 (1997): pp. 172–190.

Röger, Maren, Wartime Relations. Intimacy, Violence, and Prostitution in Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Roy, Franziska, Heike Liebau, and Ravi Ahuja (eds.), „When the war began we heard of several kings“. South Asian Prisoners of World War I Germany. New Delhi: Social Science Press, 2011.

Toye, Hugh (ed.), Subhash Chandra Bose: The Springing Tiger. Bombay: Jaico Publishing House, 1978.

Timm, Annette, “Sex with a Purpose. Prostitution, Venereal Disease, and Militarized Masculinity in the Third Reich”. Journal of the History of Sexuality 11, no. 1/2 (2002): pp. 223–255.

Vandana Joshi, Sri Venkateswara College, University of Delhi

MIDA Archival Reflexicon

Editors: Anandita Bajpai, Heike Liebau

Layout: Monja Hofmann, Nico Putz

Host: ZMO, Kirchweg 33, 14129 Berlin

Contact: archival.reflexicon [at] zmo.de

ISSN 2628–5029